Bicycles Ride, Bogus Checks do Not

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

On June 7, 1890 Thomas Nugent announced he would be erecting “two five-story flats and stores” on the east side of Ninth (later Columbus) Avenue, just north of 74th Street. He had hired architect Gilbert A. Schellenger to design the mirror-image apartment houses. Completed the following year they were a pleasing blend of Romanesque Revival and Renaissance Revival styles. Their brick facades were embellished with stone and terra cotta capitals, intricate panels and delicate trim. Each building held a store at ground level.

The apartments were spacious, although not especially inexpensive. An advertisement on May 30, 1895 offered “7 light rooms and bath with heat $33.” That monthly rent would be equal to just over $1,000 today.

Bicycles were a nationwide obsession in the 1890’s and the tenants of the two buildings were not immune. An August 6, 1893 newspaper included an article “Fair Athletes / New York Women Who Believe Muscle Is Worth Having.” It reported on the activities of the Excelsior Cycle Club and mentioned that among the “good riders” was “Mrs. I. B. Fleming, No. 305 Columbus avenue.” A tenant of 307 Columbus Avenue was equally passionate about biking. Mrs. J. S. Miznu signed a petition in 1895 asking the city to install a dedicated bicycle path from the Upper West Side to downtown.

He witnessed a drunk lurch into a lady causing her to nearly stumble onto the tracks, saved by the heroics of a bystander. “The narrowness of the express platforms makes it certain, sooner or later, that with the surging crowd which comes down upon this narrow space people will be pushed in front of moving trains, and at any time, in case of rush, a calamity is likely to take place.”

The residents were middle-class professionals. Jerome B. Melville was a mortgage and loan broker and his wife Josephine speculated in real estate. John J. Donahue, who would live in the building well into the early 20th century, worked for the Department of Docks and Ferries as a Dock Master. In 1902 he made $1,500 per year, about $47,000 today, which he supplemented with his position as Commissioner of Deeds. Around the same time Police Sergeant Patrick F. O’Neill lived here. In 1906 he became eligible for promotion to Captain.

In the meantime, the northern store was home to Harry A. Flagge’s grocery store for years. Flagge was a man of strong convictions and he fired off a letter to The New York Times in February 1905 complaining that there were no protective railings on subway platforms, notably the 1 Train. He witnessed a drunk lurch into a lady causing her to nearly stumble onto the tracks, saved by the heroics of a bystander. “The narrowness of the express platforms makes it certain, sooner or later, that with the surging crowd which comes down upon this narrow space people will be pushed in front of moving trains, and at any time, in case of rush, a calamity is likely to take place.”

In the summer of 1908 Lester Hoffstadt, alias Charles Morton, passed a forged $25 check in Flagge’s store. It amounted to a loss of about $717 in today’s money for Flagge. His only satisfaction was seeing Hoffstadt arrested “on the charge of giving bogus checks.”

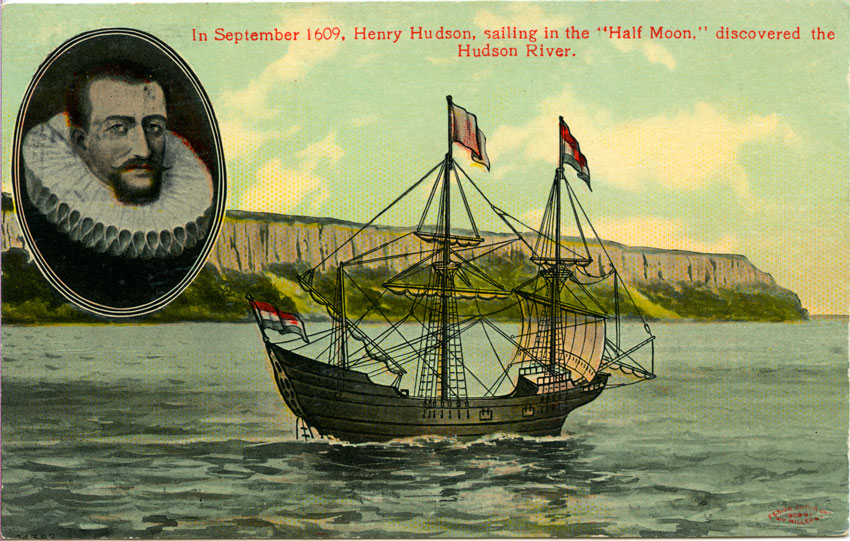

In 1909 the entire city—but particularly the Upper West Side residents—were excited about the Hudson-Fulton Celebration. The two weeks of festivities would include fairs, parades and “spectacles” to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Robert Fulton’s successful steamboat and the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s discovery of the Hudson River. Among those who were especially interested as Charles K. Moore, a civil engineer and great-grandnephew of Robert Fulton.

The 50-year old had been staying with the family of chemist Louis A. Johnson at 307 Columbus Avenue for a few months. On September 16, 1909 he wrote a letter to Herman Ridder, the President of the Hudson-Fulton Centenary Committee, asking politely if there would be special provisions for descendants to view the parade or take any other part in it. He went on in great detail as to the accomplishments of his family and ended “I merely drop you this line for your consideration.”

Moore read his letter to Louis Johnson, then walked into his bedroom. He then took his life by swallowing cyanide of potassium and was dead less than an hour after writing his letter. The reason for his unpredictable suicide was never discovered.

Harry A. Flagge had been in the grocery business for 37 years in 1916 when he explained out to a reporter from the New York Herald why food prices were going up. He said in part that “the growth of the city has driven farms so far away that the cost of getting foodstuffs to metropolitan markets is constantly increasing, all of which leaves the burden almost entirely upon the housewife.”

“the growth of the city has driven farms so far away that the cost of getting foodstuffs to metropolitan markets is constantly increasing, all of which leaves the burden almost entirely upon the housewife.”

Half a century after the buildings were completed the Columbus Avenue neighborhood had changed and the out-of-date apartments attracted less respectable tenants. Orian Gonzales was on the Federal Government’s list of Communist voters in 1942. And 17-year old Edmund Jones was one of 11 members of a gang they called Burglary, Inc. Half of the group was under the age of 18. He was arrested with his cohorts in January 1946. The New York Post reported that they admitted to an orgy of more than 200 burglaries” and added “it was unofficially estimate that their forays totaled more than $50,000 in stolen valuables.” (More in the neighborhood of $645,000 today.)

At the time the southern storefront was home to Abner Glauberg’s bar. He and every other tavern owner in 1946 was crippled by the Government’s wartime order to reduce beer production by 30 percent to save grain for impoverished, hungry Europe. The New York Evening Post reported on April 3 “Abner Glauberg, 305 Columbus Av., spent a frantic day on the telephone pleading with distributors to bring him a small supply.”

Things got worse for the two old buildings in 1947 when they were converted to Single Room Occupancy rooms, 21 per floor. It was a configuration that lasted until 1966 as the Columbus Avenue neighborhood turned around again. That year the combined buildings were converted to six apartments per floor.

In 1971 Sylvia Hirsch opened Miss Grimble in the space formerly home to Abner Glauberg’s bar. Her pastries like pecan pie and chocolate cake were popular, but it was her “creamy cheesecake,” as described by New York Magazine, for which she became a household name in Manhattan. The Miss Grimble would be a fixture on Columbus Avenue through the last years of the 1980’s.

Sadly 305-307 Columbus Avenue lost its cornice sometime in the 20th century, and the once-vibrant contrast of brick, stone and terra cotta is lost today under a coat of gray paint. Nevertheless, Schellenger’s handsome design is mostly intact above the ground floor, waiting to be uncovered one day.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

305-307 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 305-307 Columbus Avenue: