Spilt Milk at the Saybrook

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In July 1890, architect Richard R. Davis filed plans for two flat, or apartment, buildings for developer F. J. Hillenbrand. The five-story structures at 309 and 311 Columbus Avenue would be completed the following year at a cost equal to more than $1.7 million today. Each building held a retail space on the ground floor.

Davis designed the buildings–named The Saybrook–to appear as one; their romantic Romanesque Revival facades perfectly balanced. He successfully hid the fact that the northern building was 19-feet wide while 309 Columbus Avenue was almost double that width at 32 feet.

The two commercial spaces could not have been more different. On February 20, 1892 The New York Times reported that two saloon owners, Philip Maling and Robert H. Mulch, were vying for the liquor license for 309 Columbus Avenue. The article pointed out that Maling was hoping to transfer his license from another saloon, while Mulch’s application was for a new one. It is unclear which man won that battle.

Next door to the saloon was the Jonathan Butter Company “milk store,” run by Charles P. Fink. Stores like his were sometimes called dairy stores, because they also sold items like butter and cheese.

Residents of the apartments were middle-class professionals. Among the tenants in 1896 were Henry P. Luhrs, a clerk; Sabastian Bach Mills who played piano at the old Academy of Music on East 14th Street, and Augusta E. Smith. The widow of Henry W. Smith, she ran a dry goods store two blocks away at 352 Columbus Avenue—most likely once her former husband’s business.

Patrons who entered Charles Fink’s milk store on the morning of March 17, 1897 might have been surprised to find someone else in charge. They would read later of the tragedy that had befallen the proprietor. Fink lived in a fourth-floor apartment on West 76th Street with his wife and three children, the oldest being 10 years old. The Sun reported bluntly, “Charles P. Fink shot himself in the head” and The Evening Telegram said he “was found lying on his bed with a bullet hole in his right temple.” He was taken to Roosevelt Hospital where, despite being fatally wounded, he was arrested (suicide was a crime).

In the 19th century, suicide cast shame on families and they almost always did their utmost to hide the fact. Mrs. Fink insisted that it was an accident. “He kept a revolver under his pillow,” she explained. “I was always afraid to touch it, so he generally put in into the bureau drawer as soon as he got up.” But on that day, she said, he had forgotten, and she therefore did not make the bed until he came home for lunch. She asked him to remove it.

Belle Leffert was walking over the cover when it blew off. “She was lifted at least seven feet in the air,” said the article. “The force of the explosion was so great that Mrs. Leffert’s clothing was torn almost completely off her body and she was badly cut and bruised.”

“I don’t know how it happened, but he must have struck it against the drawer in trying to get it in. The revolver went off, and he fell back with a great hole in his temple.” She told reporters, “He never thought of such a thing as suicide. He was too good to his family for that.” Police were not convinced. The Sun reported “The bullet entered the right temple, and according to the police, took a course right across the forehead, trending slightly downward, which they think a stray or accidental bullet would not have done.” The Evening Telegram noted “The store, which is a general supply depot for milk, butter and eggs, was left in charge of a boy.”

Expectedly, Charles Fink died. One week later, on March 20 an auction was held of “the fixtures, lease, milk route, etc., of [the] dry and milk store.” It was taken over by Curley & Todd, which ran a second store on East 49th Street.

In 1904 the dairy store was being operated as the Locust Farm Co. and the former saloon in 309 Columbus was vacant. That space was leased Hampar O. Ambrookian, an immigrant from Armenia, for his Oriental rug store. He not only sold rugs but offered repairing and cleaning services as well.

At the time, the tenants upstairs included Edward Jouffret, who was the “elevator man” in an upscale apartment building on West 33rd Street. A year earlier, on October 12, 1903, he had been walking near the corner of Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street when exploding gas blasted a manhole cover into the air. The heavy iron cover, said The Evening Telegram, was “blown skywards until it struck the elevated station overhead with a crash and then fell, scattering men and women right and left.”

The force of the explosion alone injured two women. Belle Leffert was walking over the cover when it blew off. “She was lifted at least seven feet in the air,” said the article. “The force of the explosion was so great that Mrs. Leffert’s clothing was torn almost completely off her body and she was badly cut and bruised.” Far luckier was Edward Jouffret. The metal cover smashed to the pavement at his feet, missing his head “by about two inches.”

Margaret O’Connor shared her third-floor apartment with her 74-year old father, Frank Bernard. He was the victim of a bizarre accident on the morning of July 3, 1905. He arose at around 3:00 to go to the bathroom. Not long afterward Margaret realized her father was not in his room and looked for him with horrifying results.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported “Bernard entered the kitchen by mistake and in groping about in the dark went through an open window. He struck the paved areaway on his back and was knocked senseless for a few minutes.” Looking out the window Margaret saw him and got help from other tenants. He was taken to Roosevelt Hospital. The newspaper reported “He suffered a severe shaking up and scalp wound and a possible fracture of the skull.” Doctors felt that “because of his age he is not likely to recover.”

In January 1906, Hampar O. Ambrookian filed charges of swindling against Charles Ackron. He said that earlier that month he had received a letter from Thorne & Co., a hotel and brewers’ supply company, requesting Oriental rugs for their offices on the seventh floor of the Pulitzer Building. He was promised cash payment and he delivered about $500 worth of rugs (about $14,700 today). But his efforts to get paid went unanswered. Instead, he got another “order” for another $700 worth of rugs to be delivered to “George Billings, Jamaica, L.I.” This time Ambrookian went to the police. They found Charles Ackron (“with a long police record,” according to the New York Herald) at that address. It is unclear whether Ambrookian ever recouped his $500 loss.

At least three tenants made their livings in transportation—William Devaney was a streetcar conductor, Patrick Fitzgerald was a taxi driver, and William L. Bentley was a private chauffeur for A. T. Hardin, who lived on Riverside Drive. On the evening of March 28, 1909, Bentley was driving Hardin’s vehicle alone in Queens when he struck 15-year old Charles Clanser. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported “Young Clanser was pretty badly hurt…Dr. Costello, the ambulance surgeon, found that he had a compound fracture of the nose, internal injuries, and a possible fracture of the skull.” Bentley was arrested, but later released on bail pending the outcome of the boy’s injuries.

Five years later Patrick Fitzgerald’s name appeared in the newspapers. On January 18, 1914 at around 3:00 in the morning, he picked up four women at 66th Street and Broadway who had been at a dance. They asked to go to Coney Island. At the corner of Ocean Parkway and Surf Avenue one of the women noticed that a “long low, skeleton racer, painted gray, filled with men was following them,” as reported by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. When Fitzgerald turned onto Surf Avenue, the gray car drove directly in front of the taxi. One of the passengers waved a gun and ordered Fitzgerald to stop.

Fitzgerald’s female passengers were about to get a ride they had not anticipated. Instead of stopping, Fitzgerald stomped on the accelerator. For three blocks he raced a “zig-zag course” down Surf Avenue while the other car continued to attempt to cut him off. The article said “only the expert driving of the Manhattan chauffeur avoided a collision. All the time the men in the gray car were pointing revolvers at his women passengers, but Fitzgerald outdrove the robbers and finally dashed quickly past them and down Surf avenue to Henderson’s restaurant.”

There were three policemen in front of the restaurant. Fitzgerald pulled over and the gray car sped past. As the frantic women blurted out the story, one policeman fired a shot at the car. The officers then “jumped into a machine which was standing near and gave chase to the flying auto ahead of them.” While the two cars continued “at a terrific pace” the officers and the crooks traded gunfire.

Eventually the gray car proved too fast for its pursuers and it escaped. Police assumed that the men had seen the women’s jewelry at the dance hall and followed them. Patrick Fitzgerald emerged from the incident as a sort of hero.

No fewer than 15 men had been arrested for being drunk on Saturday night, among whom was 28-year old John O’Connell who lived at 311 Columbus Avenue. He and his four friends might have escaped notice by police had they been less rambunctious. “According to the officer the five were arrested after they had entered cars by jumping through windows.”

Hampar O. Ambrookian would continue to operate his carpet business in 309 Columbus Avenue for years. Early in 1915 the Turkish government enacted repressive measures against Armenians within its territories. In April that year 1,000 prominent Armenians in Istanbul were arrested and deported to eastern Turkey to be executed. But before that Ambrookian had already launched into action. On February 14, 1915 the New York Herald reported on a meeting of the Armenian Relief Fund Committee. “Mr. H. O. Ambrookian, of No. 309 Columbus avenue,” it said, “is treasurer of the Armenian fund, and it is expected that from $12,000 to $15,000 will be contributed at to-day’s meeting.”

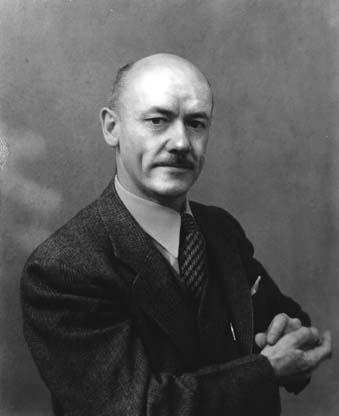

A struggling artist, George Alexander Picken, lived in the building in June 1916 when he was trying to find work. His advertisement in The New York Times read:

Artist—Young man, exceptional ability, wishes to secure position as assistant to commercial artist or with good, reliable art firm; lettering, figure work, illustrations, &c.

Picken was still renting his apartment here in 1920 when two of his works, The Ship in the Drydock and Eagle Boat on the Hudson, were shown in the annual exhibition of The Architectural League of New York. He had not overstated his “exceptional ability” in his ad four years earlier. Today his works hang in prestigious venues like the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Prohibition did not put an end to drinking and intoxication, it simply sent it underground. On July 6, 1920 The Standard Union reported “Not since the advent of prohibition has there been so many cases of intoxication as marked the calendar in the Coney Island court before Magistrate Walsh Sunday.” No fewer than 15 men had been arrested for being drunk on Saturday night, among whom was 28-year old John O’Connell who lived at 311 Columbus Avenue. He and his four friends might have escaped notice by police had they been less rambunctious. “According to the officer the five were arrested after they had entered cars by jumping through windows.”

By 1933 the store at 311 Columbus Avenue was home to Albert’s Beauty Shop, which would remain for more than a decade.

A renovation of the buildings completed in 1983 resulted in five apartments per floor, plus two in the new penthouse (unseen from street level). That year the Parachute clothing store opened in 309 and around 1985 David’s Cookies opened in 311. Other stores throughout the next decade included the pricey Neuchatel Chocolate Shop which replaced David’s Cookies in 311 in 1999 (a pound of chocolates cost $36 that year), and Cuban-born stylist Oribe Canales’s salon, Oribe, in 309. Today Paper Source operates from 309 and the women’s clothing shop OSKA is in 311.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

309-311 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 309-311 Columbus Avenue: