A Human Birdfeeder at the Kenmar

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Henry G. Gabay started his career rather humbly as a plumber working for the firm of Butcher & Butler. In 1877, he and a co-worker, Timothy McAuliffe, took over the firm, renaming it McAuliffe & Gabay. They soon turned their attention to real estate development.

In 1891, the firm commissioned the architectural firm of Thom & Wilson to design three similar flat houses on the northwest corner of Columbus Avenue and West 77th Street. The corner building would contain two stores on the avenue side. Completed the following year, the five-story structure was faced in yellow brick and trimmed in brownstone above the stone base. While the avenue elevation was purely Renaissance Revival in style, the entrance at 101 West 77th Street was lavished with Romanesque elements like the squat columns, which upheld the foliate-carved arches.

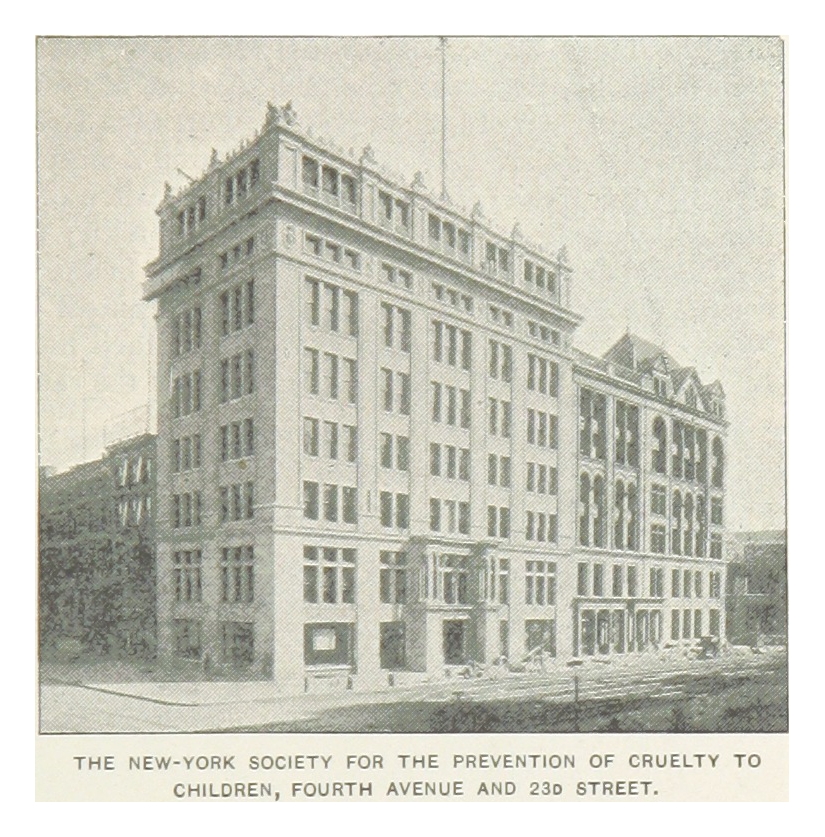

The residents were professionals, financially comfortable enough to have at least one servant. Well-to-do women were expected to involve themselves in charity work and Mrs. Bischoff was no exception. Her donations to the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in 1893, however, may have fallen short of the generous gifts of more wealthy patrons. Throughout the year she gave: “1 piece of oil silk, 1 piece of black silk, 1 lace handkerchief, 1 pair of curtain loops, bunches of flowers, 3 pillow cases, and a roll of cotton batting.”

Living in the building at the time were Edward Arden Noblett and his wife, Bertha. Noblett ostensibly ran an employment agency. His first brush with bad publicity came after he hired Jennie Race as a cashier on October 4, 1893. Jennie earned a salary of $10 per week, but Noblett required her to give him $150 “as a guarantee of her honesty.” A few days after that he closed the agency, taking the young women’s money with him. He was arrested, but, because he returned the money, he was not prosecuted.

The New York Times said he was “once known as the ‘prince of the bunco men,’” and called him “one of the last and best-known representatives of the old-time confidence men of the glib tongues and carefully staged intrigues. He began by ‘selling Coney Island’ and wound up by passing off on the public worthless stocks.”

The narrow escape did not stop him from resuming his scheme. On December 18, he rented a “deskroom” (a one-man office with a furnished desk) in the Morse Building on Nassau Street. The rent was $15 per month but he was given the first month free. The New-York Tribune reported, “He brought an ink bottle and some pens to the desk, borrowed a blotter from Austin Smith, of the Albemarle Paper Company, whose desk was near his in the same office, and, thus equipped, was ready for business.” Seemingly ready to resume his employment agency, he listed several jobs in the daily papers. And as had been the case with Jennie Race, each of the candidates was required to provide a deposit ensuring his or her honesty. On December 27, the New-York Tribune noted “On Saturday, Noblett was politely asked to give up his desk.”

It is unclear how long the Nobletts remained in The Kenmar, but Edward went on to became somewhat of a criminal celebrity. Upon his death in December 1932, The New York Times said he was “once known as the ‘prince of the bunco men,’” and called him “one of the last and best-known representatives of the old-time confidence men of the glib tongues and carefully staged intrigues. He began by ‘selling Coney Island’ and wound up by passing off on the public worthless stocks.”

In the meantime, the northern store was first occupied by Robert Martin’s jewelry shop. His advertisements offered “Repairing of Watches, Clocks, Jewelry and Bric-a-Brac.” When he moved directly across the street to 365 Columbus Avenue in 1905, the space was taken over by a grocer, Benjamin Schneps, who received his license for the “sale and delivery of milk” that year. (The sale of milk was closely regulated by the city government as tainted milk called “swill milk” had been a problem since the 1850’s.)

At the turn of the century, respectable citizens like corporate attorney Maurice S. Hyman, stockbroker A. S. Barnes, and real estate dealer Henry S. Brevoort lived here. Another resident placed a bewildering advertisement in the newspapers on May 2, 1901 that read: “Will ‘Hattie,’ who took valued souvenirs from Mrs. Chamberlain’s apartments on Tuesday please send pawn tickets to No. 101 West Seventy-seventh street.”

Henry S. Brevoort did not return home from work on the evening of August 2 that year. He stopped at a restaurant on Sixth Avenue that night and, according to the New York Herald, “Entering the place shortly before eleven o’clock, he ordered a hearty meal, including a sirloin steak. He was seen to put a piece of the steak in his mouth, and then he choked.” Brevoort fell to the floor and several customers tried their best to dislodge the blockage, but he was dead before an ambulance arrived.

The family of Harold C. Burr had a fright on May 24, 1906. The stockbroker’s daughter, Nellie, started to cross Riverside Drive at 88th Street that evening and did not notice an approaching automobile. The driver, William Wilkins “tooted his horn,” according to The Sun, but the terrified young woman froze on the spot.

“She was knocked down and a rear wheel of the automobile passed over her. Her back was sprained, she got a cut over the eye and her face was badly bruised.” She was taken to the J. Hood Wright Hospital, and Wilkins was released since the police felt “the accident was not easily avoidable.”

The Kenmar continued to house respectable families. Peter I. Nevius, a clerk for the law firm of J. F. Kernochan, lived here during the World War I years, as did the York family. Margaret A. C. York (known as Marie) had been courted by Dr. Sidney L. Spiegelberg prior to his joining the army. The New York Herald noted “Before leaving for abroad Dr. Spiegelberg was a caller at her home.”

Spiegelberg, who became a lieutenant in the Medical Corps., was killed in action on July 15, 1918 in France. The New York Herald said “Dr. Spiegelberg was an early victim from gas.” Two months later, on September 10, The Sun reported “The bulk of the estate, $20,000, is left to Margaret York,” The New York Herald adding “His gift to Miss York was in appreciation of their friendship.” The inheritance, which Marie deemed “unexpected,” would be equal to about $340,000 today.

The New York Times recounted, “The bag, she explained, was filled with bread crumbs. Being fond of birds, she had taken it to the park to feed the sparrows and pigeons.” She told how her aunt had fed the birds for 35 years and she, herself, had been doing so for the past ten years.

Two widows, Mary Conroy and her aunt, Mary Dillon, shared an apartment here during the Great Depression years. Both women enjoyed walking to Central Park to feed the birds. The practice landed Mary in the West Side Court on April 9, 1934.

Patrolman Frank J. Norton told the judge “he found Mrs. Conroy, with a paper bag in her hand, standing in the rain” just inside the West 77th Street entrance to the park.” He gave her a summons for trespassing on the grass. Mary denied the charges and insisted “she was standing on a well-trodden path.” She went on to pour out her heart-rending tale.

The New York Times recounted, “The bag, she explained, was filled with bread crumbs. Being fond of birds, she had taken it to the park to feed the sparrows and pigeons.” She told how her aunt had fed the birds for 35 years and she, herself, had been doing so for the past ten years. “Why, even on the coldest days and during the worst stores last Winter she hadn’t missed a day, she said.” Her pitiable story touched the judge’s heart. “Madam, you are doing a noble work. Discharged.”

Mary’s penchant for the dramatic did not stop with her release, however. The New York Times reported “Mrs. Conroy said afterward that she did not know what to do about feeding the pigeons any more, as she was afraid to return to the park.”

The second half of the 20th century saw changes come to the Columbus Avenue neighborhood. In 1975, the upper floors were renovated, resulting in six apartments per floor. The ground floor stores became eateries. The northern space was the Mexico restaurant Taco Villa in 1976 and the corner space was the Museum Café by 1987, where patrons could find what the Daily News called “wonderful burgers and other good pub food.”

In 1999 another Mexican restaurant, Café Frida, opened in the former Taco Villa space and remained there for 22 years. Currently, the owners plan to open La Covacha in the same space. The corner space was home to Mediterranean restaurant Spazzia in the late 1990’s, followed by Jacques-Imo’s, a Creole-style restaurant. The Shake Shack has been in the space since 2008.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

360 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 360 Columbus Avenue: