Life in a Residence Hotel

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

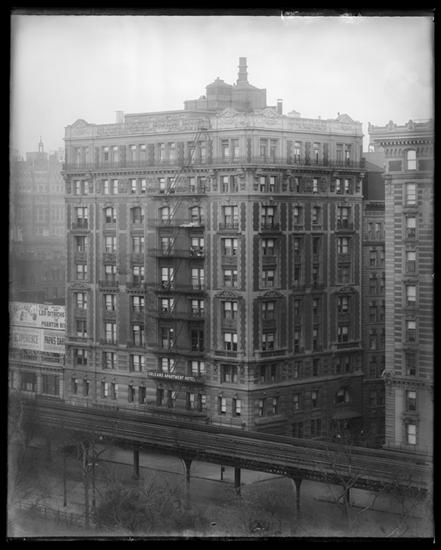

On February 26, 1898 the Record & Guide reported on the incorporation of The Imperial Construction Co. “for the purpose of carrying on a general contracting business.” The company wasted no time in getting down to business. Within two weeks it had purchased the brownstone houses at the southwest corner of Columbus Avenue and 80th Street and contracted the architectural firm of Buchman & Deister to design a 10-story “brick hotel” on the site (residence hotels were, essentially, apartment buildings except residents ate in upscale communal dining rooms rather than in their suites). Their plans, filed on March 4, estimated the cost of construction at $300,000—more than $9.5 million today.

Completed in 1899, the Beaux-Arts style Orleans Hotel vied for attention with the high-end mansions in the neighborhood. As a matter of fact, it bore significant architectural similarities to the sumptuous row of mansions on West 73rd Street between Central Park West and Columbus Avenue. There were 40 suites of from two to four rooms with bath, and four stores along the Columbus Avenue side.

The first commercial tenants seem to have been Huston & Dale, insurance agents in 412 Columbus Avenue. In January 1899 the firm announced it had branched out into real estate “with an up-town office” here. The following year Charles H. Brown opened his society florist shop in 410 Columbus.

The apartments filled with well-to-do residents, like W. H. Noyes, vice-president of the New York branch of Swift & Co., the massive Chicago meat packing firm. Leopold Herzog was a member of the dry goods firm L. Herzog & Bro. on Leonard Street. (He and his wife were enjoying a hansom cab ride through Central Park on July 5, 1903 when the horse became spooked and ran away, throwing the Herzogs and the driver to the ground. Leopold received a bad scalp wound but his wife escaped injury.) Another of the initial residents was Louis Mendham, the head of a downtown brokerage firm.

About the time that ground was broken for the Orleans Hotel, Louis Mendham attended a social event where he met the very young widow, Alice Coe Fallon. Her husband, John H. Fallon had died a year earlier, and The New York Press mentioned that Alice “had just laid aside her [widow’s] weeds when Mendham met her.” Alice, the daughter of Edward H. Coe, came from a prominent San Francisco family.

Alice may have been concerned that society would disapprove of her marrying so quickly; so, when the couple was wed on April 25, 1900, they told no one—not even their parents. A year later, however, Alice’s pregnancy ruined the secret.

Mendham moved into the Orleans Hotel and shortly afterwards Alice took a suite at the equally upscale Rudolph on Central Park West. Alice may have been concerned that society would disapprove of her marrying so quickly; so, when the couple was wed on April 25, 1900, they told no one—not even their parents. A year later, however, Alice’s pregnancy ruined the secret. On May 7, 1901 The New York Press reported, “Few persons are as successful in keeping a secret as Louis Mendham and his wife have proved themselves.” The first social event that Alice attended as Mrs. Louis Mendham was a visit to her mother-in-law to introduce herself and the infant girl.

Commonly, immigrants were seen as impoverished and ill-educated, living crushed together in tenements. And, indeed, while that was the case for tens of thousands, there were also those immigrants who landed in New York already successful and wealthy.

One such woman was Elizabeth Ambrosy, whose parents brought her from Brandenburg, Germany, around 1870. Since her childhood she had known Eugene A. Landon, who grew up to be a wealthy lumber merchant. On April 3, 1906 the two were married in the Orleans Hotel. The New-York Tribune remarked that the “wedding was quiet, only a few friends of the pair being present.” That was most likely because the groom had just divorced his wife.

Sexism was alive and well in 1908 but the telephone operator of the Orleans Hotel did not accept that fact. Anna Cassidy (who with other apartment house and hotel operators was termed a “hello girl”) was accustomed to arriving at work each morning, ordering her breakfast from the dining room, and eating at her desk just off the lobby. And that was what she did on Saturday morning, August 1, 1908. Suddenly, Albert L. Semoyer appeared and “commanded her to take her meals outside the place.” Anna, who had never seen the impertinent 29-year old before, asked him “what he had to do with it” and went back to her breakfast. What no one had bother to inform her of was that Semoyer was her new boss, the manager of the hotel.

“He strode toward her; seized her chair and jerked it away. Miss Cassidy sat down under the affront. She sat down so abruptly, in fact, that for the moment she was deprived of speech,” reported The New York Press. Semoyer then “dragged her to a seat.” Anna Cassidy pressed charges of disorderly conduct. In court, Anthony McGlynn, the hotel’s night clerk, testified on her behalf. Semoyer was charged $5 (about $145 in today’s money). The New York Press said, “Semoyer paid the fine with an expression that seemed to say he would be more careful about making young women, especially hello girls, bump the bumps.”

Living in the Orleans Hotel at the time was German-born writer Frederick Franklin Schrader. In October 1909 he won The Evening Telegram’s Short Story Contest with his “Mrs. Jackson’s Burglar,” taking the first prize of $50 in gold.

But his allegiance to the country of his birth soon caused a drastic change in the tone of his writings. He became co-editor of the weekly periodical The Fatherland the subtitle of which was Fair Play for Germany and Austria-Hungary.” He contributed scores of articles like the one entitled “American People Waking Up” in the July 28, 1913 issue; and “Are We England’s Secret Ally?” on May 5, 1915. In that article he warned “Are the American people being betrayed? Are they to be delivered hand and foot, boots and saddle, into the hands of England and Russia?”

He was also the author of the 1912 book The Germans in The Making of America. It was later discovered that Schrader was an employee of the German Consul, paid to disseminate pro-German propaganda before and during World War I.

In 1915 416 Columbus Avenue was home to the Boyd Pharmacy (a drugstore would remain in the space at least through 1938). It was around this time that the Orleans Hotel began accepting transient guests as well as permanent residents. In 1916 a single room “with use of bath” in the hall cost $1 per night (about $24 today); a room and bath cost 50 cents more; and a suite with two bedrooms, parlor and bath were $3.50 and up. Meals in the dining room cost an extra $10 per week.

While many Victorian structures fell from favor during the 1920’s and ‘30s as streamlined Art Deco apartment buildings rose, yet the Orleans Hotel never declined. In the 1930’s it was home to stockbroker Ogden Doremus Budd and his wife, the former Grace Jackson; and veteran theatrical manager and producer, Daniel V. Arthur and his actress wife, Marie Cahill.

Marie was born in Brooklyn in 1866 of Irish immigrant parents. She was well-known to Broadway audiences both as an actress and vocalist. After her marriage to Daniel V. Arthur, he produced several plays written for her and managed her career.

The Orleans Hotel experienced a glut of Soviet nationals in the Cold War years. In 1959 Second Secretary to the Consulate of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics Victor A. Ignatov and his wife lived here, as did Soviet attaché Konstantin Grigorievich Sadovnikov and Vadim Vladimirovich Sorokin, Third Secretary and his wife. Another resident was Alexander R. Sitnikov and Madame Sitnikov, Second Secretary to the Byelorussian Consulate.

The Orleans Hotel experienced a glut of Soviet nationals in the Cold War years. In 1959 Second Secretary to the Consulate of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics Victor A. Ignatov and his wife lived here, as did Soviet attaché Konstantin Grigorievich Sadovnikov and Vadim Vladimirovich Sorokin, Third Secretary and his wife. Another resident was Alexander R. Sitnikov and Madame Sitnikov, Second Secretary to the Byelorussian Consulate.

Ironically at the same time the Orleans Hotel was home to Russian immigrant Boris Gourevitch. An author, anti-Soviet activist and President of the Union for the Protection of the Human Person, he had been born in Kiev during the reign of Czar Nicholas II. A pacifist and humanitarian, between the overthrow of the Czar and the Bolshevik Revolution, he was chairman of the Union for Evolutionary Socialism. The New York Times noted “His writings in Russia included appeals for pacifism, a philosophical novel, works on the cultural life of Jews, the peoples of Russia and poetry.”

When the Soviets took power, he fled to France. As Adolf Hitler’s control in Germany increased, Gourevitch formed the Committee for the Emancipation of Jews and later the Union for the Protection of the Human Person. After arriving in New York, he wrote the 2,700-page, two volume work The Road to Peace and Moral Democracy for which he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 and 1959. He died in 1964 while still living in the Orleans Hotel.

The last decades of the 20th century saw trendy shops in the Columbus Avenue stores, like Bottecelli, Beau Brummel, the Spring Flowers boutique, and the Museum Gallery.

More recent shops include Billy’s Bakery which opened in October 2018, bocnyc, and Berkley Girl. In the meantime, developers (and residents) David Sterling and Nora Lavori received approval for a 26-unit conversion of the upper floors in August 2014, at which point the building became simply The Orleans.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

410-416 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 410-416 Columbus Avenue: