The Protective League and the Poolroom

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

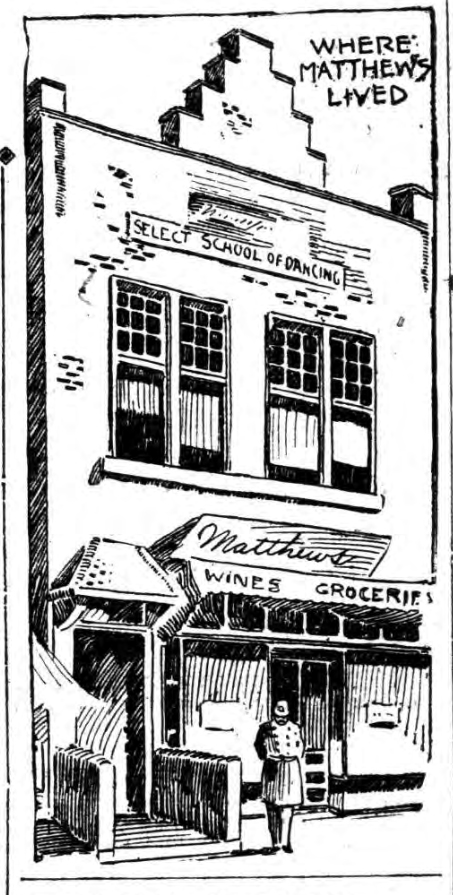

In the last decade of the 19th century, buildings designed in the Flemish Revival style dotted the island of Manhattan. An architectural reference to the city’s Dutch roots, it was most popular on the Upper West Side. In 1893 at 426 Columbus Avenue, across from the vast lawns of the brooding Natural History Museum, Clarence Fagan True designed the building as Joseph R. Hennessy’s oyster market and restaurant.

True used iron spot brick, brownstone and terra cotta to create the quaint store at ground level and meeting hall above. The little building mimicked a Flemish stable with a large, offset archway—like the double doors of a carriage house—framing the commercial entrance. To the side, a narrow entrance led upstairs to meeting rooms.

Hennessy and his family lived in two bedrooms, a parlor, kitchen and bathroom behind the commercial space. The upstairs meeting hall was rented out for additional income.

Hennessy ran into problems with the construction of the elevated train on August 25, 1894–quite literally…[he] was knocked out of his buggy yesterday afternoon by workmen with an ‘L’ road pillar at Eighty-sixth street and Columbus avenue and slightly injured.”

Hennessy ran into problems with the construction of the elevated train on August 25, 1894–quite literally. The New York Herald reported “Joseph R. Hennessy, proprietor of the restaurant at No. 426 Columbus avenue, was knocked out of his buggy yesterday afternoon by workmen with an ‘L’ road pillar at Eighty-sixth street and Columbus avenue and slightly injured.”

It was another piece of bad luck for Hennessy who was in serious financial trouble. He sold the oyster market and restaurant to Irish immigrants Terrance and Michael McManus.

They quickly ran into problems when an undercover officer walked in on Sunday, September 8, 1895. According to the New York Herald, “Terence McManus, proprietor of an oyster saloon at No. 426 Columbus avenue, who sold liquor to Policeman Walters on Sunday, September 8, was fined $500.” It was a hefty penalty, around $15,700 today.

One of the early organizations to use the hall was the newly formed Lutheran Church of the Advent, which held its first services here on December 19, 1896. The roomy space became popular with neighborhood groups.

With the arrival of the third owner, it seemed that the little building was cursed with bad luck.

While Joseph Hennessy was still struggling with his oyster business, John Herman Matthews ran his sheep ranch in New Mexico. In 1896 he sold the ranch and moved his family to New York. Using the money from the sale, he opened several businesses, one after another, and in May 1897 tried his hand at selling men’s furnishings. His shop on Broadway survived only four months before it, too, failed.

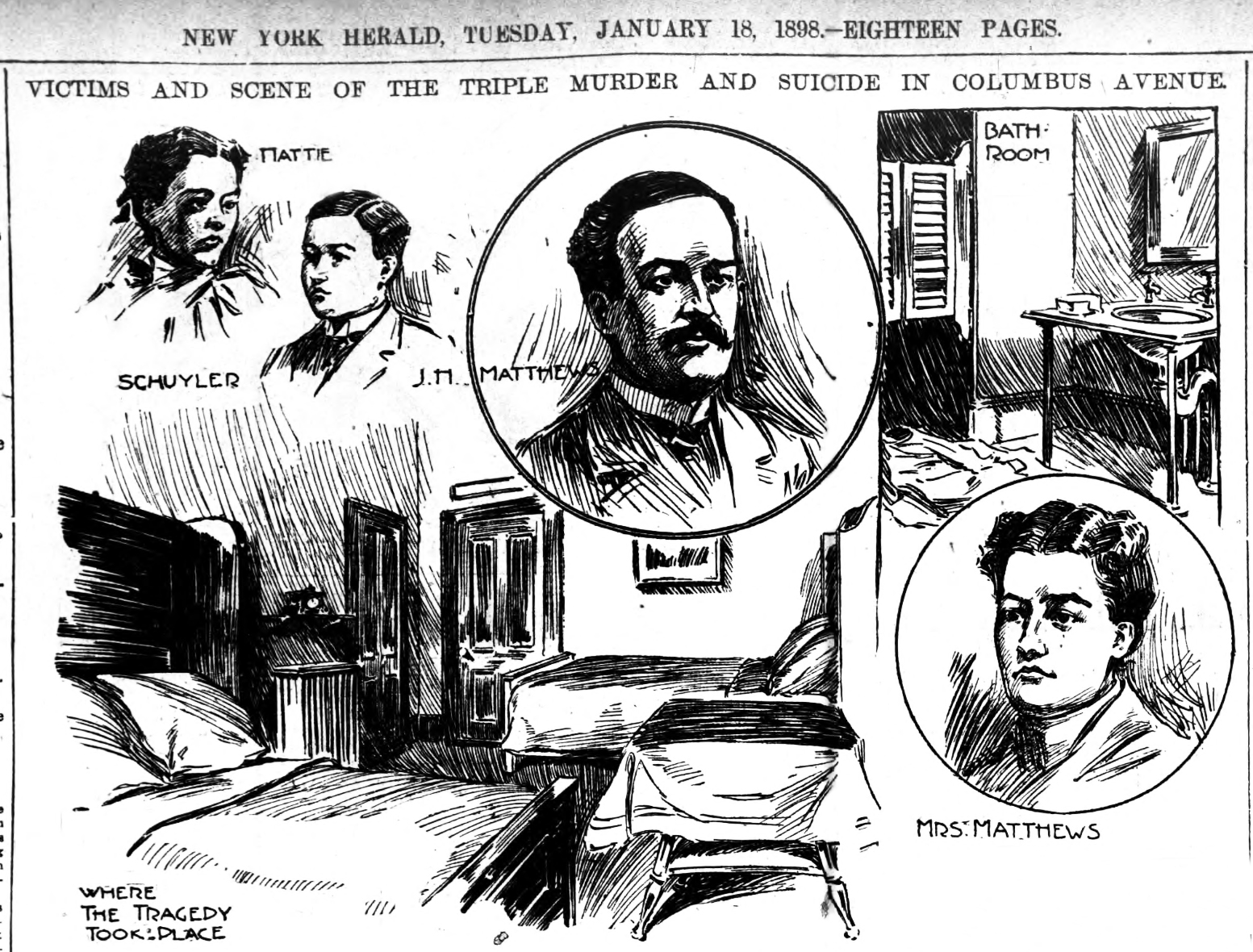

The dejected Matthews then stumbled across the former oyster market on Columbus Avenue. He leased the space and started yet another business – a grocery. John Matthews tried hard to eke out a living for himself and his wife, Minnie, and their two children Hattie, twelve, and Schyler, ten.

This little grocery seemed, finally, to be working. Neighbors and relatives reported that the family was financially stable and, apparently, happy. But no one seemed aware that Matthews had been ill for a few years with no hope of a cure and his wife was suffering from consumption. The pair decided the best way out was death.

On a busy Saturday night in the store, January 18, 1898, only three months after opening, Matthews left his clerks in charge. He put his children into a deep sleep by giving them champagne and put them to bed. Then he and Minnie began writing letters to loved ones.

One of Mrs. Matthews’ read in part, “We are both tired of life as we can’t get well. Mr. M. as well as myself is not, nor has been, well for years though he looks healthy…Oh my darlings I hate to take them, but I can never go and leave them to suffer and fight life alone.” She asked the acquaintance to dress her children for their funerals. “I want Hattie in white and flowers, my dear little man in a new suit if necessary.”

Matthews then opened the gas jets so the family would die of asphyxiation. But he could not wait. When the gas had no rapid effect on him, he killed his unconscious family with a hatchet, then shot a bullet into his brain.

Organized in March of 1891, the West Side Protective League had one goal: “to restrict as much as possible the liquor traffic on the West side above Fifty-ninth Street.” By 1896 it had added to its cause the suppression of “gambling houses, houses of prostitution, and all persons and places of immoral character; and to observe and report to the proper authorities any failures of the police to properly enforce the laws” in the neighborhood.

It was an unspeakable misfortune that unnerved the Columbus Avenue neighborhood for months. However, the meeting hall continued to be leased. At the time of the heartbreaking tragedy, the hall was being used by two dance academies, the Lutheran Church, a kindergarten, and the West Side Protective League.

Organized in March of 1891, the West Side Protective League had one goal: “to restrict as much as possible the liquor traffic on the West side above Fifty-ninth Street.” By 1896 it had added to its cause the suppression of “gambling houses, houses of prostitution, and all persons and places of immoral character; and to observe and report to the proper authorities any failures of the police to properly enforce the laws” in the neighborhood.

The League was disbanded in 1900 and, in an ironic twist, that same year a Special Committee to the New York State Legislature reported hard “evidence against a poolroom at 426 Columbus Avenue.” Indeed, Costello’s billiard rooms had renovated the commercial space directly beneath the meeting rooms where the League had rallied against such evils.

The billiard parlor became a Western Union Telegraph Company branch office by 1903. The quaint little building survived throughout the 20th century with little change. In the late 1970’s it was home to Central Carpet and today the entire building is used as a clothing store.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

426 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 426 Columbus Avenue: