Spreading it on Thick: 490-494 Columbus Avenue

by Max Chavez, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

The three conjoined structures at 490-494 Columbus once constituted a handsome elevation built in a simple fashion reminiscent of the popular Italianate style. While the building’s architect and exact year of construction are unknown today, photos from the 1940s show a sturdy five-story building, with each individual apartment structure being four bays wide. The structures’ top floor cornices were subtle, supported by equally understated brackets as additional ornamentation. Each of the three buildings also featured fire escapes that descended from top to bottom, connected to tall, narrow windows capped by simple decorative hoods. Additional visual interest was provided by rusticated masonry that ran along each floor’s bays.

490 Columbus is likely the most famous of the three addresses as it was the birthplace of Hellmann’s Mayonnaise. Twenty-three year-old Richard Hellmann arrived in the United States from Germany in 1903 with years of experience working for food production companies both in his home country and in the United Kingdom. Two years after his arrival, he ventured into food retail, opening up a small store at 490 Columbus which he sold for a European vacation when the business became profitable. When Hellmann returned from his sojourn, he still had ample funds to buy back the store.

The biggest draw at Hellmann’s deli was his wife’s salads. Hellmann concluded the key ingredient was their homemade mayonnaise, so he began to package it in bulk. The mayonnaise was such a success that they soon owned a fleet of delivery trucks to distribute the coveted condiment—this eventually gave way to a Hellmann’s factory in Queens, whereupon the Hellmanns departed from their 490 Columbus storefront.

Hellman concluded the key ingredient was their homemade mayonnaise, so he began to package it in bulk.

Soon, Hellmann’s factories could be found nationwide. His burgeoning mayonnaise business was eventually acquired by Best Foods, a mayonnaise competitor, in 1932 and Hellmann’s has been a Best Foods product ever since. Hellmann, by then a comfortable millionaire, was on the board of Best Foods for years after the merger; he passed away in 1971 at the age of 94 in Greenwich, Connecticut. Today, Hellmann’s is the most well-regarded mayonnaise brand in the United States and is considered the gold standard for the beloved and creamy sandwich enhancer.[1]

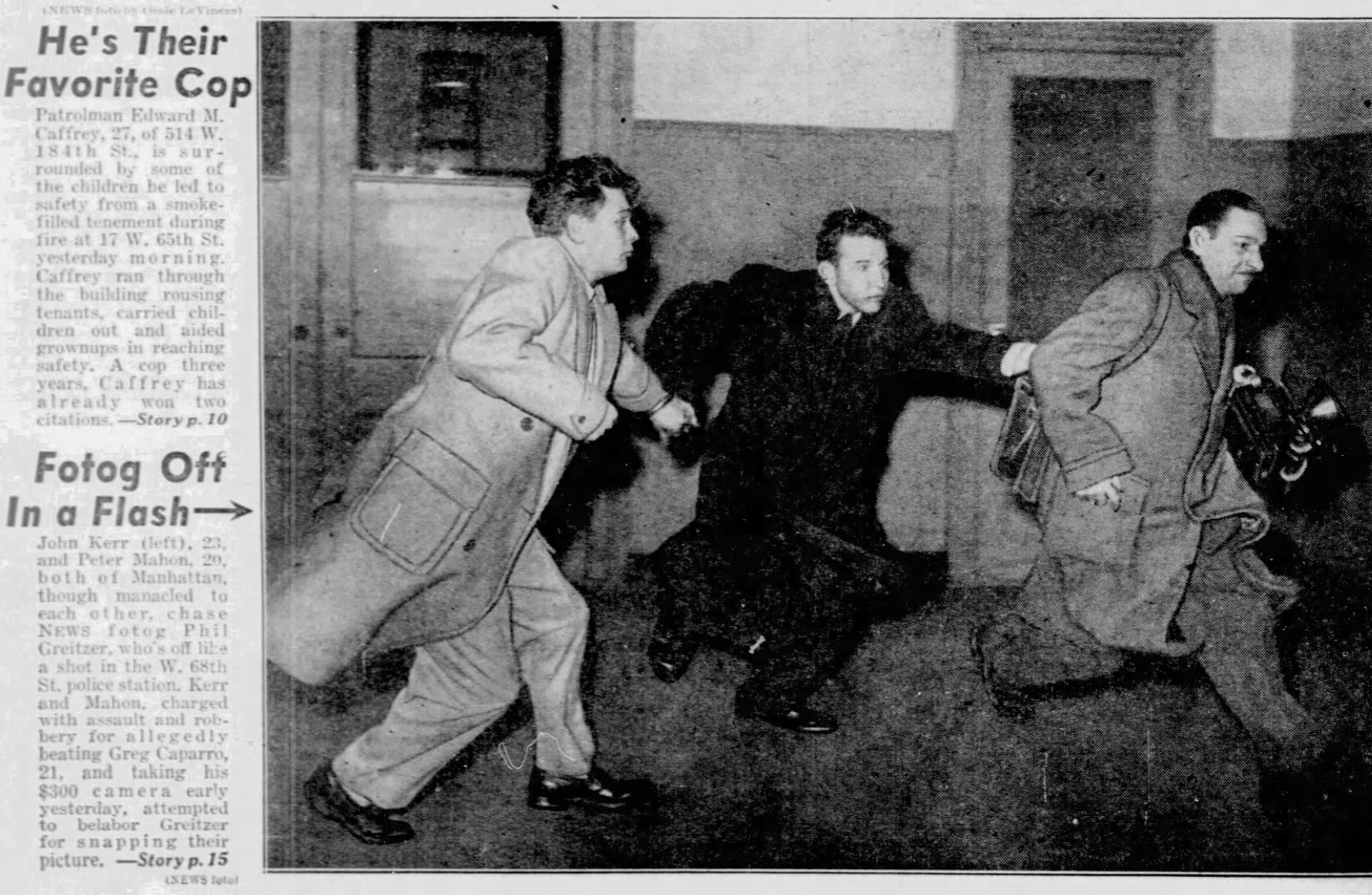

However, this address had tenants far less savory than the mayonnaise made famous there. Peter W. Mahon lived at 490 Columbus when his name was listed in 1955 as one of two men charged with assault and robbery. Mahon and his accomplice, John Kerr, attacked twenty-one-year-old student Gregory Caparro and took off with his $300 camera. The Daily News pointed out this sad irony: Mahon’s brother was killed just a few blocks away two years prior committing the exact same crime against an off-duty police officer who shot him dead in self-defense.[2]

The retail storefront space of 492 Columbus was for a while a stationery store, a common business at the time, as 494 Columbus next door also sold stationery during the 1920s—but only 492 had the misfortune of making it into newsprint more than once. There was first an 1895 run-in between traveler Joseph R. Clark and store owner Daniel Callahan in which Clark, while paying for some newspapers, passed off a worthless check to the tune of $5 and was promptly arrested days later when the check bounced.[3]

Seven years later, Callahan found himself again in the papers when he was called as a witness in the landmark, multi-year trial of Roland B. Molineux who was charged with the murder of Katherine J. Adams. By this point in the trial, Molineux had already been convicted and was in the midst of multiple appeal processes focused around the question of admissibility of evidence. Molineux was believed to have sent a package of poison-laced medicine to the private post office box of Harry Cornish who unknowingly provided the medicine to Adams, his wife, killing her. The prosecution had suggested that Molineux has committed additional earlier murders, a strategy later deemed inappropriate for the trial, setting a future legal standard about admissible evidence and the inability to use previous crimes as evidence in a trial.

The defense, in an attempt to imply that Cornish was the actual murderer, claimed that Cornish had never even owned a private mailbox. Callahan was brought to the stand and asked if he recognized Cornish and if Cornish ever rented a mailbox at his 492 Columbus storefront. Callahan responded in the negative to both questions until he left the stand, whereupon he stopped in his tracks, changed his mind, and proclaimed that he did indeed recognize him. Although later, Callahan explained that he was friends with the victim’s son and recognized Cornish that way, the moment was theatrical enough to have merited a write-up in multiple newspapers of the time. Molineux, ultimately, was acquitted. [4] [5]

An 1899 conflagration gravely burned a candy store owner and her employee next door at 494 Columbus, as reported by the New York Tribune. Owner Christina Langfeld was reported to have accidentally knocked over a gallon of benzine in the store’s backroom and called to worker Henry Schumacher for help in cleaning it up. Schumacher, in an attempt to illuminate the room, made the horrifying mistake of striking a match—the benzine immediately ignited and engulfed Langfeld’s lower body. Schumacher, too, was burned in an attempt to save her from the flames. The fire eventually spread through all five stories of the building causing city firefighters to heroically scale the building’s exterior signs to reach residents. The fire was thankfully extinguished and none of 494’s residents nor its candy store employees lost their lives.[6]

The benzine immediately ignited and engulfed Langfeld’s lower body. Shchumacher, too was burned in an attempt to save her from the flames.

This same ground floor space was later the setting for a 1939 assault against bar owner, James Horan. Three men, one of them a United States Army corporal stationed at Governors Island, flew into a rage at 4 in the morning when Horan insisted on closing his restaurant for the day, resulting in the men stabbing the barkeeper. It seems Horan was only injured by the attack, likely having been convinced for good that the customer isn’t always right.

A 494 Columbus resident was caught up in a police versus prisoner confrontation deemed “the battle of the Black Maria” by the Daily News. James J. Walsh, 26, had been arrested on charges of carrying out a robbery and was in the back of a police van with another prisoner, Byron Berry, and a New York police officer when Berry lunged for the officer’s gun while the van was speeding down the West Side Highway. Walsh jumped into the struggle, surprisingly in defense of the officer. The fight carried on from 72nd Street to Greenwich Village as the drivers were unable to hear the conflict raging on inside. By the time the van was stopped and the doors were opened, Walsh and the officer were “badly mussed”, but Berry was “unconscious, his skull split by blows from [the officer’s] gun.” The headline reads “Cops Win as Usual,” unsurprisingly omitting the aid Walsh offered in the conflict.[7]

Continuing the streak of bad luck that seemed to befall people at 494 Columbus, resident Thomas Keane was found dead August 6, 1950, on the grounds of the Hayden Planetarium. The Daily News cited his cause of death as a heart attack.

What Came Next? Read about the Sarah Anderson School.

References:

[1] Daily News, 5 Sep. 1982, Pg. 252.

[2] Daily News, 20 Jan. 1955, Pg. 15

[3] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 16 Aug 1895, Pg. 12.

[4] The Buffalo Review, 22 Oct 1902, pg. 1.

[5] New-York Tribune, 22 Oct 1902, Pg. 2.

[6] New York Tribune, 27 Apr 1899, Pg. 5.

[7] Daily News, 19 Jul 1940, Pg. 4.

Max Chavez is an architectural historian based in Chicago, Illinois.

Keep Exploring

Learn More about Block 1214

Located here today!