The 1890 Brockholst Apartments

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

As the Upper West Side developed, its individual personality quickly became evident. Real estate operators formed the West Side Association to fight the extension of Manhattan’s grid plan of avenues and streets—they preferred that their own grid be tilted to align with Broadway. Architects embellished mansions and rowhouses with gargoyles, stained glass, turrets and towers—in stark contrast to the formal styles preferred on the opposite side of Central Park.

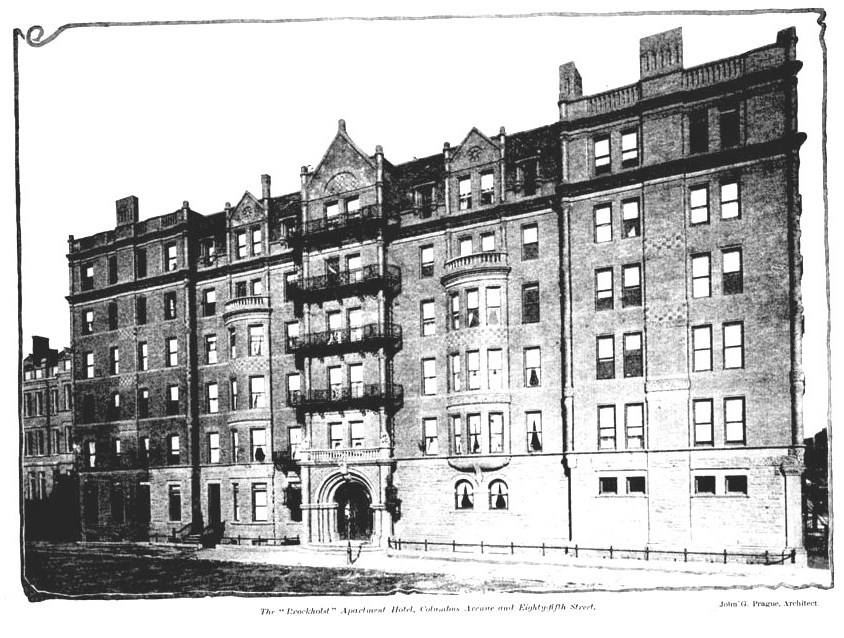

And West Siders were much quicker to embrace another concept–apartment living. Five years after the hulking Dakota flats opened in 1884, John G. Prague began designs for another, The Brockholst.

The land around the corner of Columbus Avenue and 85th Street was once the country estate of the wealthy, respected Livingston family. It was now owned by T. E. D. Powers who partnered with Prague to develop the plots. The pair would build more than 230 residences in rapid-fire succession. The Real Estate Record and Guide said in 1890 “They have created a neighborhood.”

Their Brockholst, on the northwest corner of Columbus and 85th, was named for Brockholst Livingston, a Supreme Court Justice and brother-in-law of John Jay. The building was completed by December 20, 1890 when The Real Estate Record and Guide praised it as “a truly noble building.” The publication said “It is a fitting complement to the extensive and magnificent improvements with which Messrs. John G. Prague and T. E. D. Powers have embellished the West Side.”

Six stories tall, the Romanesque Revival pile of brooding brick and brownstone embodied the architectural taste of 1890s Upper West Siders. The foyer doors at No. 101 West 85th Street were deeply recessed within a medieval arched entranceway, over which an unidentifiable yet nonetheless scary beast held watch. Two three-story bays bowed away from the façade, one of which read The Brockholst in wacky 1890s lettering that danced across an intricately-carved band. Rough-cut blocks, checkerboard stonework, and an irregular roofline interrupted by chimneys pretending to be clustered chimney pots combined in a romantic and massive structure.

Prague worked with Tiffany & Co. in decorating the lobby. A massive carved limestone fireplace stood at northwest corner, its mantel reaching nearly to the ceiling. That ceiling, designed by Prague, was of aluminum and executed by Tiffany. The main staircase featured a bronze railing and marble steps. From the lobby the barber shop, café, and dining room could be accessed.

The private dining room, decorated in white and gold and illuminated by stained glass skylights, was intended originally for residents and their guests. The Record and Guide deemed the Wilton carpeted room “richly decorated.”

Connected to this dining room, slightly hidden by portieres, was a restaurant, open to the public who entered on Columbus Avenue. The rooms were designed so that they could be combined into one large space for receptions and other events. It would seem that Tiffany had its hand in the decoration of the restaurant as well, for the Record and Guide described fixtures as “a jar from which three lilies rise, and from these lilies branch out petals which form the electric lights.”

The Brockholst was technically a residential hotel, rather than flats like the Dakota. The Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide explained it as “the latest type of hotel—that wherein the families occupy their suites of apartments—their homes, all the year round, and are enabled to obtain their board in the building, if they so choose, or obtain it partly or wholly, outside the building.”

Unlike transient hotels, the suites included kitchens, so “occupants can make their own culinary arrangements, if they desire.” The great attraction of the Brockholst and similar residence hotels was that the household could forego the problem of domestic help. Maid and cleaning service was provided by the building.

Upstairs, suites ranged from one room and bath, costing $350 a year, to nine rooms and bath, costing $1,500. The rent on a nine-room apartment would translate to about $3,400 a month today. The hallways had expensive Wilton carpeting, the building was steam heated and the electric lighting was powered by dynamos in the basement. (The unreliability of electricity prompted the installation of “combination of gas and electric lights.”)

Prague worked with Tiffany & Co. in decorating the lobby. A massive carved limestone fireplace stood at northwest corner, its mantel reaching nearly to the ceiling. That ceiling, designed by Prague, was of aluminum and executed by Tiffany. The main staircase featured a bronze railing and marble steps. From the lobby the barber shop, café, and dining room could be accessed.

Less than one year after the Brockholst opened, it was sold. The first hint appeared in the Record and Guide on October 24, 1891. “John G. Prague, it is reported, has sold the ‘Brockholst’ apartment hotel…for about $477,000.” The rumor had truth, although it would be weeks before negotiations were finalized. Finally, on December 13 The New York Times confirmed the completed sale, for $432,000.

“Now that the sale has occurred, dealers feel that the market has been strengthened thereby, and have become more hopeful than ever that the Winter season will be a prosperous one,” said the newspaper.

The buyer was Randolph Guggenheimer, a self-made millionaire and member of the legal firm Guggenheimer & Untermyer. He continued providing the upscale residents of the Brockholst with superior services and conveniences.

Among the residents were William J. Hancock, superintendent of the Eastern lines of Wells-Fargo Express Company, his wife and two children. Their neighbors were all families of affluent businessmen.

The concept of a roadway through Central Park under consideration in 1892 prompted a vociferous backlash from New Yorkers—many of them of course, on the Upper West Side. Two of these were little girls who lived in the Brockholst. Mabel and Marion did not sign their surnames when they sent a letter of protest by messenger to the meeting of the Park Commissioners’ meeting on May 21.

“The letter told how they used the west side of the Park to play in every day, what a great blessing it was to them and to all their playmates, and how they hoped they would never be deprived of it,” reported The New York Times the following day.

In 1893 King’s Handbook of New York City called The Brockholst “superior.” That year resident Thomas Lansing Masson became literary editor of Life magazine. A poet and humorist, he was a regular contributor of humorous articles to various publications. On Tuesday October 24, he married Fannie Zulette Goodrich in Hartford, Connecticut. Newspapers announced that, “The bridal couple will reside at 101 West Eighty-fifth Street after Jan. 1.”

German-born Samuel Van Praag was emblematic of the prosperous Brockholst residents. He had been with the steamship agents Phelps Bros. & Co. for 16 years in January 1894, was a member of the Produce Exchange, and served on several committees. The Evening World said he “was regarded as a remarkable well-informed man on marine matters.”

But for several years the 46-year old bachelor had suffered from a variety of medical problems. Finally, his illnesses forced him to resign. His condition became too much for him and on the morning of June 1, 1894, he fired a shot from a 32-calibre revolver into his heart. “Despondency, due to illness, is assigned as the cause,” said The Evening World that afternoon.

In 1899, Floyd B. Wilson moved from Brooklyn into the Brockholst. Born in Watervliet, New York in 1845 his extensive education included studies at the Jonesville Academy, the University of Michigan and the Ohio Law School. Wilson and his wife, the former Esther M. Cleveland, had two daughters—Pearl Cleveland Wilson, who was away at Vassar, and 10-year old Beryl Madeline.

Aside from his corporation law practice, which “has earned for him a reputation all over this country,” according to The Successful American in 1899, Wilson had had a wide-flung career. He had been principal of the Euclid Avenue Seminary in Cleveland, lecturer on elocution and English literature at Racine College, poet of the University of Michigan, the author of the novel Uphill, and had translated the Spanish comedy La Coja y el Encojido. Wilson had also written several articles for Harper’s and other magazines on travel “and metaphysical subjects.”

He was also president of the mining firms Santa Barbara Gold Placer Company and the Arizona Gold and Copper Company; vice-president of the Copper Hill Mining Company; and a director of the Santa Fe and Grand Canon Railway Company.

The precocious 15-year old Walter Jones lived in the building in 1902. He joined a new organization connected with Public School No. 166 that year. It was formed to encourage “self-activity” among its all-boy membership. In October that year a journalist from The New York Times was taken with the model racecar Walter had fashioned.

“Master Jones’s little toy is fashioned after such as the ‘White Ghost’ and other fliers, and there is nothing in the visible mechanism missing”

Walter may have been offended at the reporter’s calling his model a “little toy.” He insisted “he was not yet satisfied with the interior mechanism, and was at work at home on a half-horse power machine that would really run when he got through with it.”

Another tragic death in the Brockholst occurred in 1904. The young wife of 24-year old real estate dealer Frank T. Pressman had died the year before. He brooded over his loss for a year.

In the apartment next door lived Pressman’s mother, a Mrs. Adams. On March 31, 1904, he sold all his furniture explaining that he was about to embark on an extended trip to California. Four days later, he did not appear in the dining room for breakfast. Concerned, his mother notified the superintendent.

“The skylight was broken open, and James Dillon, a hallboy, was lowered into the room,” reported The New York Times on April 3. “He was almost overcome with the illuminating gas, but managed to open the windows and doors.”

Frank T. Pressman had committed suicide by inhaling gas. Dr. A. Richard Stern deduced he had been dead “for several hours.”

There was apparently a glut of vacant apartments that year. An advertisement in The Sun on November 8 offered “apartments of three, four, five and eight rooms and bath; maid service included; elevator attendance night and day; caterer in building; inspection invited.”

In 1914, Buildings and Buildings Management outlined the operation of the dining room, which, while run by an independent restaurateur who provided his own linens and silverware, was closely supervised by the Brockholst management. “Care is taken by the house that no cause for complaints as to menus, cuisine, or service crops up among the tenants and general supervision over the quality and nature of food supplies according to the season of the year is the rule.”

Residents were charged a flat rate of 40 cents for breakfast and luncheon and 75 cents for dinner. Or, if the resident preferred, a weekly charge of $10 covered three meals a day.

The magazine mentioned the current rental rates. “The Brockholst contains a great number of housekeeping apartments of six to eight rooms and kitchen, renting from $900 to $1000 a year. There are some non-housekeeping apartments of three and four rooms, also, renting at $40 to $60 a month apiece.”

The building’s superintendent, William Featherstone, reiterated the attraction of the Brockholst since its inception. “The servant problem is such a mighty one nowadays that every family pays pretty close attention when you offer them a feature making them wholly independent of the maid, cook or serving-man.”

He told Supreme Court Justice Shearn on August 27, 1915 that he left the country with “State funds amounting to about $300,000 in United States gold.” (The Government of Mexico put the amount closer to $450,000.) But, that was only for the good of the country, he insisted. “I was responsible for these funds, and I did not intend to leave them behind for the robbers.”

Perhaps the Brockholst’s most celebrated resident was the ousted Governor of the State of Yucatan, Mexico, Abel Ortiz Argumendo, and his family. When he fled the revolution in 1915, he came to New York and took an apartment in the Brockholst in April.

Almost immediately, the circumstances of his fleeing and the amount of cash he brought with him were an issue. He explained that the “revolution” was actually “bandits and other parties” set on taking over the Yucatan. So “I decided to remove the Governorship to Havana, Cuba, until there was a legal President in Mexico.”

He told Supreme Court Justice Shearn on August 27, 1915 that he left the country with “State funds amounting to about $300,000 in United States gold.” (The Government of Mexico put the amount closer to $450,000.) But, that was only for the good of the country, he insisted. “I was responsible for these funds, and I did not intend to leave them behind for the robbers.”

In 1918, Arnold Krakauer lived in the Brockhorst with his wife, Minnie Jacobs Krakauer. The couple had been married since 1892 and Krakauer worked for Harry S. Stevens at the Polo Grounds.

Stevens was, as described by the New-York Tribune, “the well known purveyor of double-jointed peanuts and hot frankfurters at the Polo Grounds and caterer to the metropolitan racetracks.” Stevens’ company would continue to serve hot dogs and peanuts at Shea Stadium, Churchill Downs, Fenway Park and other sports venues until 1994 when it was taken over by Aramark Concessions.

The happy home life of the Krakauers began to fall apart in October 1918 when, according to Arnold, Harry M. Stevens and Minnie were intimate in the Brockholst apartment. The affair continued for a full year—always in the Krakauer’s bedroom–and then in May 1920 there was an encounter at No. 302 Central Park West.

The wronged Arnold Krakauer sued his wife for divorce in September 1920; then sued his boss for alienation of affections. The New-York Tribune’s headline on September 5 announced “Harry Stevens Sued As Home Wrecker.”

At the time of the Krauaker-Stevens scandal, Henry H. Lloyd was still in residence and would stay on for some time. Also in the building were Harriet Beecher, the daughter of Henry Ward Beecher, and her daughter Margaret Beecher White who taught Christian Science.

In 1932 78-year old Amelie von Ende died. The Polish-born concert pianist and writer had been well known in musical circles. She contributed to several magazines on German and French literature and on music, and often shared the concert stage with her German violinist husband.

By the time of Amelie’s death, the Brockholst had been eclipsed by modern apartment buildings. When it was sold to an investing syndicate headed by Milton R. Leader in 1950 there were 41 apartments and six stores in the building. Within six years, the number of apartments had risen to 52 as the sprawling larger apartments were broken up.

In 2009 an ambitious renovation and restoration effort was initiated which upgraded the apartments and turned attention to the careworn façade. Artist Sergio Rossetti Morosini was commissioned to restore the endangered brownstone sculptures.

The Brockholst emerged with its wonderful carvings and fanciful elements intact; allowing us to imagine the well-heeled residents of the 1890s who passed through the oaken double doors.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

520-526 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 520-526 Columbus Avenue: