975 Columbus Avenue aka 74 West 108th Street

by Tom Miller

On March 10, 1899, architect Michael Bernstein filed plans for four five-story “brick flats” at the southeast corner of Columbus Avenue and 108th Street. Their developers, Ableman & Rosenbaum, would spend $20,000 each to construct the nearly identical structures (equal to about $758,000 in 2024). The partners apparently over-stretched their finances, and they lost all four buildings to foreclosure in June 1900, shortly after their completion.

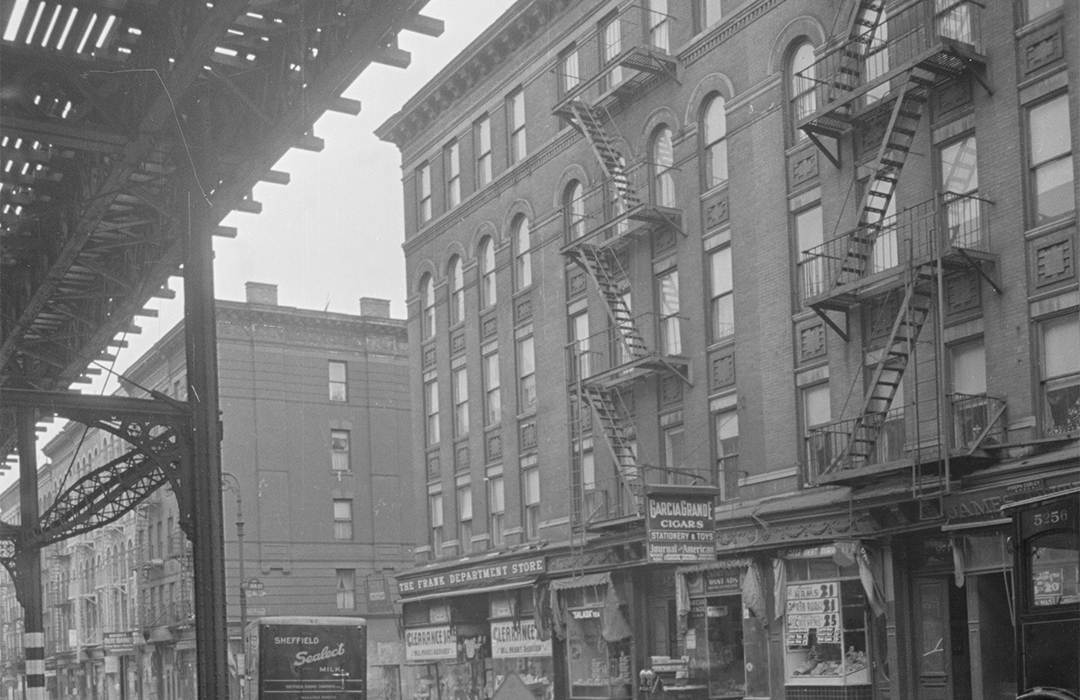

The structures were clad in gray brick and trimmed in stone. Bernstein’s restrained Renaissance Revival design featured arched openings at the fourth floor and brick panels within the spandrels above the second and third floors.

The corner building, 975 Columbus Avenue was slightly different. While the residential entrances of the others were tucked between storefronts, this one was located around the corner at 74 West 108th Street. Its elaborately carved Renaissance inspired frame sat atop a box stoop, which also boasted intricately carved panels.

The corner store was leased to Joseph DeRosa, who opened a fruit stand. He remained until around 1908, when the space became a New York Central Lines ticket office.

Apartments consisted of seven “light rooms” (meaning they had abundant natural light), and bathrooms with “porcelain bath.” Rents were $36 per month in 1910, or about $1,190 today.

She listed her profession as “a hairdresser for the Vanderbilts.”

The apartments were home to middle-class tenants. Among the first was T. F. Webb, who, unfortunately, did not enjoy his apartment for long. On February 7, 1901, the New York Morning Telegraph began an article saying, “Knockout drops, it is believed, caused the death of T. F. Webb of 74 West 108th street, who was found senseless early yesterday morning in front of 71 West Tenth street.” Webb had gone downtown the previous evening to attend a business meeting. His family expected him home before midnight. Found unconscious, he was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital where he died. Attendants there said that “there were no marks or bruises of any kind on the body.” According to Webb’s friends, he was not a drinker.

Rose M. Smith, who lived here at the time, had a somewhat enviable job. She listed her profession as “a hairdresser for the Vanderbilts.” In July 1905, Rose prepared to move from 74 West 108th Street to 339 East 41st Street and hired two local teens, James Rogers and Austin Butter, to move her trunk. Among the things inside were items she needed for her business—wigs and switches (what today would be called extensions). Instead, the youths made off with the trunk. On July 6, The Sun reported that Rose M. Smith was “mourning the loss” of her trunk and its contents. The items, valued at $700, “were distributed among a long list of pawnshops,” according to the police.

The Fyfe family occupied an apartment here by 1911. The family’s son Jimmie, who was 14 years old that year, was a constant source of vexation. On August 9 that year, The Sun reported, “The Children’s society is of the opinion that the only way to keep Fergus O’Brien and Jimmie Fyfe in the path of rectitude is to hogtie them.” The article said, “Their whereabouts is always a problem.”

Two weeks earlier, authorities had notified Mrs. Fyfe that Jimmie and his friend were in Syracuse, New York. She forwarded the train fare for both boys to come home. Once back in Manhattan, the boys did not return to their homes but, instead, jumped on a New York Central box car full of hay at 109th Street. “Special Policeman Patterson, looking for tramps, smelled smoke as he passed the car and discovered the boys stretched on the hay bales enjoying freedom and smoking cigarettes at a rate that made Patterson think the car was on fire,” reported The Sun. The boys were arrested and Patterson “marched them down to the Children’s society.” When Justice Hoyt turned the delinquents over to their mothers, the women opined “that the natural perversity of their youngsters is beyond words.”

Two years later, Jimmie Fyfe’s name was back in the newspapers. On January 28, 1913, the New York Evening Telegram said that the teenager walked into the central police station in St. Louis, Missouri and “confessed that he had stolen $125 from his employers in New York.” He told the desk sergeant, “The better man in me has possession of my conscience and I want to be punished.”

The family of Jacob Selzer lived here in 1917. He and his wife had two young adult daughters, Matilda and Dorothy. Matilda was an accomplished musician and advertised regularly looking for work. She always used only her first initial, perhaps fearing that identifying herself as a female might hamper her chances. In December 1918, for instance, an advertisement in the Evening Telegraph read, “Cornetist, open for Christmas and New Year’s engagements. Write M. Selzer, 74 West 108th st.” and two months later, an announcement in The Billboard read, “Cornetist at Liberty for Position—Write M. Selzer, 74 West 108th st.”

He told the desk desk sergeant, “The better man in me has possession of my conscience and I want to be punished.”

Dorothy Selzer had a more traditional job. She worked at the Medical Supply Depot on Greenwich Street. But in March 1919, she was laid off. On April 1, she left home “brooding” over her unemployment, according to her family. The following day Mathilda received a note with a $5 bill inside. It read,

When you receive this I’ll probably be gone forever. Please don’t worry about me, as it is the only thing I could do. I can’t stand this mental depression any longer, and if I live it will only be worse for you and for me. I do so want to live, but there is no more joy in life left for me, so it is better so.

It breaks my heart to do this after you’ve worked so hard for me, but I can’t help it. Please try to comfort mamma and papa and tell them not to worry.

Poor mamma, she has had so much trouble, I’m crying my eyes out for her. I am sending my rings in my purse, in another package.

She had written the note from the rented room at 502 East 105th Street where her body was found that afternoon. She had committed suicide by inhaling gas.

Prohibition was enacted in 1919, and it did not take resident Augustus Sheehan long to break the law. He owned a garage, as did John Haff, who lived nearby on West 104th Street. The men were arrested on the night of January 8, 1920 after investigators found three suitcases in their automobile. Inside them were 56 bottles of liquor.

Maria Cesterow moved into her son’s apartment in 1973 after her daughter-in-law left him with their 3-year-old daughter, Pamela. On the afternoon of August 26, 1973, Maria took the girl to Central Park. At around 6:00 that evening, Maria turned away from Pamela to pay an ice cream vendor. When she turned back, the toddler was gone. Maria searched on her own for an hour before notifying police. It is unclear whether the girl was ever found.

A renovation completed in 1998 resulted in three apartments per floor. Of the original four, 975 Columbus Avenue is the only building to retain its cornice and its overall original appearance.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 975 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Steve Hlay!