In the mid-1980s, preservation policy in the US and New York City was still nascent. In comparison to today, New York was a lawless playground for building owners and developers. The thriving real estate market prompted growth and made demolition appealing. People were looking to make a quick buck flipping their properties in New York. In 1986, real estate markets were peaking for the decade, and Ivan Stux, then owner of the now landmarked John B. Leech House, wanted to capitalize on his investment.

The Leech House, completed in 1892 and designed by Clarence True, is one of the finest freestanding mansions on New York’s Upper West Side. At the northeast corner of West End Avenue and 85th Street, the stately mansion was commissioned by speculative developer Richard Goodman Platt as a massive single-family house. Less than three weeks after construction began, John Burgess Leech, a successful, British-born cotton broker with nine children, purchased the home. The family filled the home’s many rooms. Its exterior, clad with rusticated sandstone base, light brick, and a red tile roof, was designed in a cohesive mixture of Romanesque Revival, Gothic Revival, and Elizabethan Revival styles. Its heavy stonework and rounded half-turret lend a particular mass to the building, however the whimsically carved, sandstone detailing of this home make it inviting and an irreplaceable part of the neighborhood.

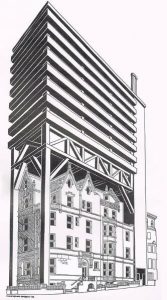

This was not Stux’s concern. Long before Stux came into ownership of the building, it had been divided into apartments, the value of which blinded him from the beauty of the home. He saw this symbol of the Upper West Side’s opulent origins as a barrier to the value of his corner property. Realizing the publicity nightmare demolishing the Leech House would attract, he devised plans to “save the home” and capitalize on its vacant airspace. In a misconceived, elongated, and bastardized attempt at “pilotis,” slender columns that support the mass of a building, Stux’s designs fell short of their intention to imitate successes of popular modernist architects, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in iconic structures like New York’s own Seagram Building. What resulted was a ridiculous design that resembled Kevin Roche’s unrealized plans for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or an AT-AT Walker from George Lucas’ Star Wars films. Raised on four steel stilts, a ten-story glass tower was planned to be erected just above the roofline of the Leech House, desecrating the home below, which would remain occupied by Stux’s unlucky tenants.

Stux’s plan via Instagram

Community members were disgusted by the atrociously poor design of the oblong and looming structure, but more so by the way it disenfranchised the existing True house that they had come to know and love. At the time, neighbor and community spokesperson, Ben-Ami Friedman, told The New York Times, “He could restore this very handsome building, but what he is doing is coming in and installing truly an atrocity in terms of architecture. It’s like putting this modern dunce cap on top of this very elegant, late-19th-century building.” Vested community members, such as local neighbors, preservationists, and elected officials, had trouble gaining traction in their efforts to save this house. The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) had shown interest in listing the home as an individual landmark, a feat they initially achieved. However, Stux had tangled the Commission in an arduous legal battle, temporarily revoking the designation. The fate of this Clarence True masterpiece was still uncertain.

An unlikely hero came to the aid of the old Leech House. The Department of Buildings (DOB) was ultimately responsible for saving the house. While the DOB originally approved Stux’s horrific plan, when the LPC, Landmark West!, and other vested community groups urged Buildings Commissioner Charles M. Smith Jr. to reconsider the decision, Commissioner Smith argued against Stux’s proposal. The plans did not meet NYC zoning code. At a width of only 27 feet along the avenue, the Leech House is governed by narrow-building, or “sliver,” regulations. This legislation limits building height to 45 feet, unless the structure “abuts a contiguous and fully attached existing building street wall.” While the upper stories of the egregious addition were attached to an adjacent building, the Leech House was a freestanding home, and therefore, Stux’s plans were denied, as it could technically be classified as too narrow. In the meantime, as Stux struggled to reformat his plans to meet the DOB’s zoning requirements, the LPC was able to overcome Stux’s legal hurdles and designate the Leech House as an individual landmark in 1988. Clarence True’s beautiful turn-of-the-century home was saved.

The moral dilemma surrounding historic preservation, zoning, and building code was and remains contentious. Is it right to “stymie” economic growth and technological innovation in the name of retaining our heritage? Or, is reverence for the past a form of progress in itself? The case-by-case nature of architectural preservation makes these questions nearly impossible to answer. What may be right for one building could doom another, making it nearly impossible to write legislation that consistently achieves the desired outcome. In the 1980s, the DOB exploited a loophole that ultimately saved Clarence True’s John B. Leech House. Today, loopholes in zoning legislation, concerning floor area ratio (FAR) and void mechanical space, are exploited by greedy developers building massive supertalls that consume neighborhoods by turning the streetscape into a ghost town and further impede small businesses. Loopholes have always existed in zoning and building legislation, and they will, most likely, continue to exist. While some loopholes may be advantageous to local advocates and preservationists, like in the case of the John B. Leech House, legislation should be written in a way that achieves the desired solution without “a hidden backdoor.” Legislation should work as intended. The diverse nature of the built environment makes it impossible to stop the exploitation of loopholes in strange and unique cases, but if a legislative loophole is being continuously exploited at the expense of the community, then legislation should be changed. Gaining consistency in this historically inconsistent industry should be the goal.

Renderings as noted. Images courtesy Alice Lum via Daytonian in Manhattan