West End Collegiate Church

245 West 77th Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Road to building a church

Dating back to when New York was largely referred to as New Amsterdam, the first Western religious order to build a church in the city was the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church. The congregation gathered in a loft above a gristmill in 1628 in Lower Manhattan and built its first church in 1642. The Dutch church’s Collegiate system was developed shortly after.

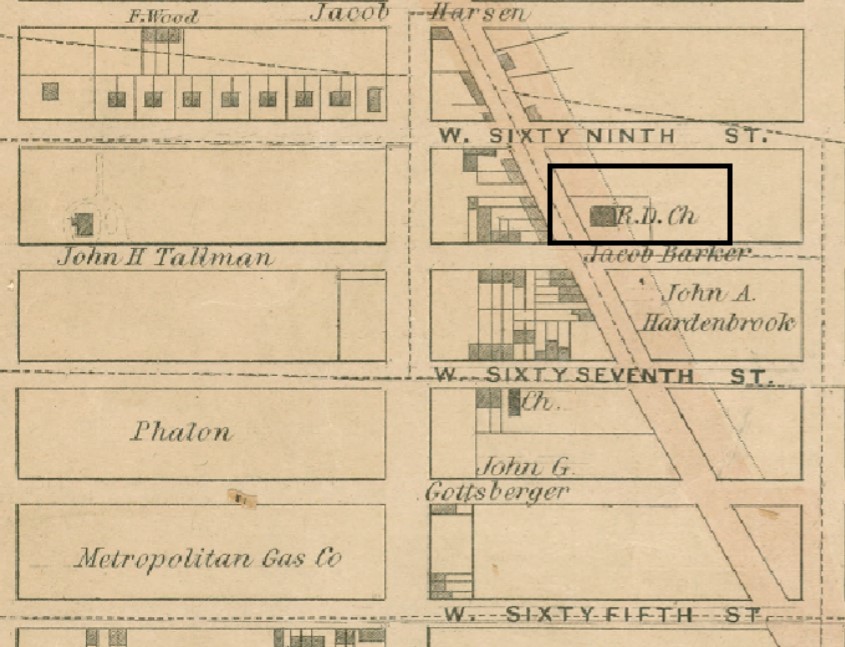

Although an earlier ‘Dutch Reformed Church’ stood on the old Bloomingdale Road, near West 68th Street, which was torn down around 1869 for the widening of Broadway, the Collegiate arm of the Dutch church first moved to the Upper West Side in 1891. On October 16, 1890, the Consistory of the Collegiate Church instructed “the committee on a new site west of Central Park” to price several lots to construct a church and school building. The congregation had several churches downtown and on the park’s east side but decided to expand westwards, following a general migration trend apparent in the 1880s and 1890s.

The committee scouted several locations in the West 70s. They were given $102,500 to purchase a lot on West 76th Street and West End Avenue but soon found out the site had already been sold, and would now cost more than their budget. In December, the committee raised the new asking price, about $110,000, to offer the site, but ultimately decided upon buying seven lots on the northeast corner of 77th Street and WEA for $89,000. The complex was projected to cost $150,000.

In June 1891, the Consistory voted to add $5,000 to the building budget so that tiles could be used instead of slate on the roof. The organ, which cost $5750, was donated by a congregant. Next, the committee had to choose who would act as pastor of the West Side branch. They ultimately decided on Reverend Dr. Henry Evertson Cobb, starting on a salary of $7,000. The congregation was all ready to go; they just needed a structure in which to worship.

Architects and their wealthy patrons had become tired of the predominance of Romanesque-style rowhouses that lined the streets of the still-expanding neighborhood

Dutch-style revival

Robert W. Gibson was chosen to design the Dutch church. About a year before he was commissioned by West End Collegiate, Gibson was working on another iconic Upper West Side church, St. Michael’s Episcopal. St Michael’s was consecrated in 1891 but took longer to complete, so work on both of these iconic churches would have overlapped. Gibson is also credited with designing the Albany Cathedral upstate and the Botanical Museum in the Bronx. Gibson, an Anglo-American architect, graduated from the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and in 1881, he moved to New York to pursue his career working on banks, churches, and residences.

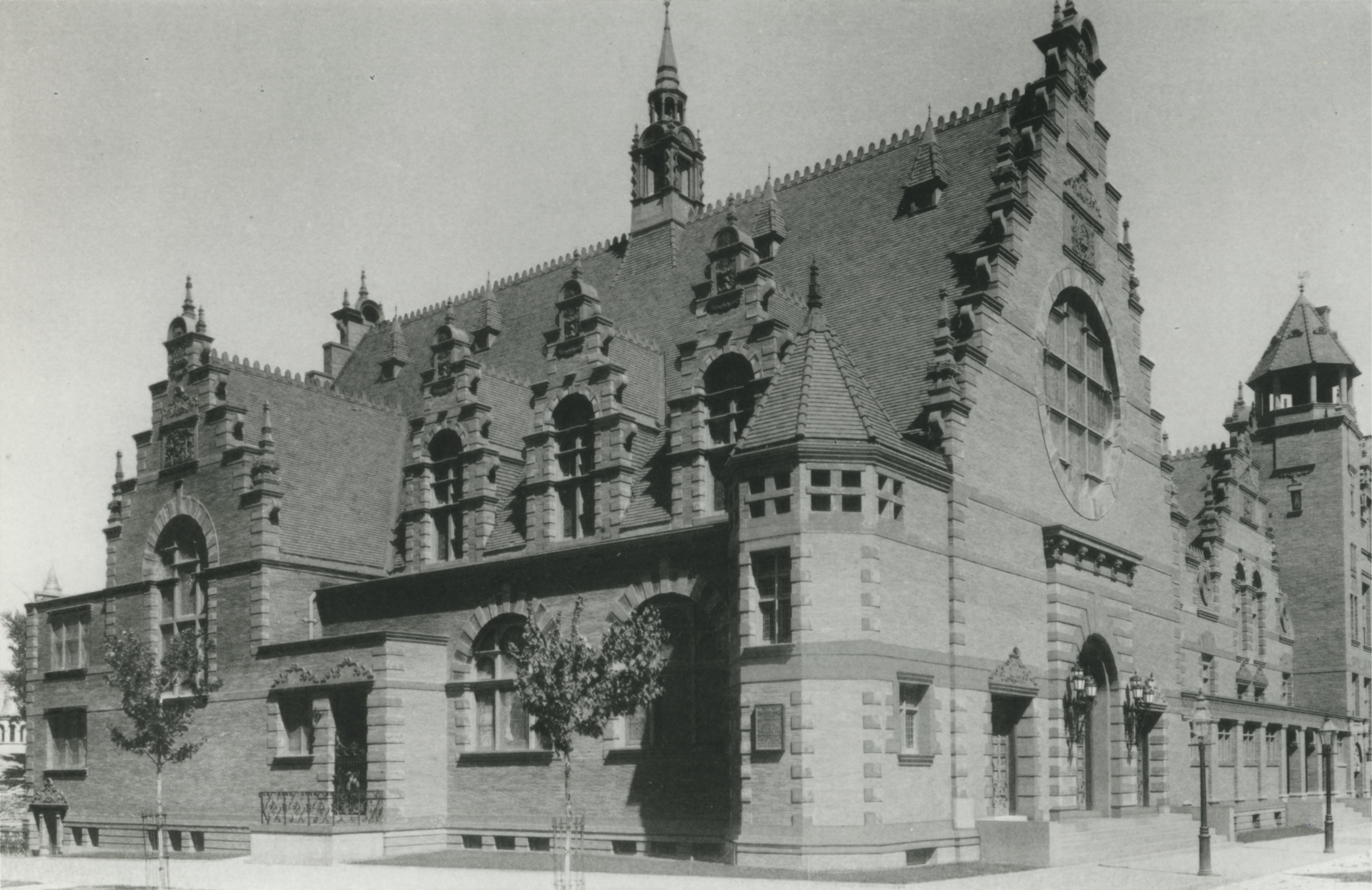

Gibson capitalized on the growing trend towards the Dutch architectural revival style on the Upper West Side. Architects and their wealthy patrons had become tired of the predominance of Romanesque-style rowhouses that lined the streets of the still-expanding neighborhood. Thus, the unconventional ‘Dutch’ architectural revival took hold in the 1880s and 1890s following the construction of two groups of houses by McKim, Mead, and White and a separate row by Frederick B. White on West 78th Street and West End Avenue, which remain some of the few extant examples of this early revival.

Gibson’s church was a more literal interpretation of the Dutch and Flemish influence, most likely the result of collaboration with the Collegiate Church, which had deep ties with Holland and Dutch heritage. Gibson styled the church after a Meat Market built in 1606 in the city of Haarlem, The Netherlands. The reproduction of the elaborate stepped gable on the facade provides the unifying theme of the entire complex, the gable is repeated in the chapel and the school building. The Church yearbook, published in 1893, gave an in-depth description of the newly built church:

The style of architecture is Dutch, modeled upon the old buildings of Haarlem and Amsterdam. This style has the picturesque qualities of the Gothic, with more originality, and is historically appropriate. The materials used are long, thin bricks of a Roman pattern and brown in color, trimmed freely with quoins and blockings of buff terra cotta. Some very picturesque panels carved with the coats-of-arms of the church and of past benefactors are also in terra cotta.

The design choice was reminiscent of old New Amsterdam, and an architectural style that was once conspicuous in the lower part of the city, now mostly disappeared. The interior reflects the medieval inspiration, more in a Renaissance style. Yellow walls fill the rear of the altar with carved oak rafters lining the ceiling. The Tiffany windows, donated by congregants and contributors, however, steal the show as usual.

A ‘quaint’ church

The “quaint” church, as described by the New York Times, was dedicated on November 20, 1892, two years after the initial planning meetings. They wrote, praising the innovative design, “Among the many new churches which spring up every year in New York none, perhaps, is more notable than this, for it represents almost the first instance in which an architect has boldly out loose from the precedents in church architecture which have ruled in New York in order to go directly to the Netherlands and choose a style which obtained there when this city was founded.”

The 750-seat capacity church was filled to the brim during the ceremonies, “There were no seats to be had. Many persons stood in the aisles.” The church would prove to be a significant fixture in the neighborhood, holding important discussions on prison reform, and being a source of comfort for the Dutch community during World War II. It was also one of the wealthiest congregations in the city, only second to Trinity Church. Many prominent funerals were held within the church like that of society florist Charles F. Thorley.

Thorley first opened his florist shop at 16 in 1874 and it soon became one of the largest businesses in cut flowers. His work graced the most exclusive events and prestigious venues including the Vanderbilt family homes and the Waldorf Astoria hotel, and his store on Fifth Avenue had throngs of patrons lined around the block every week. Thorley’s business also broke ground by being one of the only stores in the industry to employ an all-African American staff. His sudden death came when he suffered a stroke on a train traveling back to New York from Princeton in November 1923.

He was described as a flamboyant figure, and his funeral was not the least extravagant. The procession began at the Plaza Hotel, where he lived, and continued uptown and across the park to the church on 77th Street. The altar was of course banked with the finest flowers and autumn leaves. Over 1,000 people attended, including several high-ranking officials in the city.

After almost 40 years of service, Rev. Cobb retired from the pastorate of West End Collegiate in 1931. He would remain active in the Collegiate Church however, as a senior minister, a position similar to that of a bishop. Following a year’s vacation and an increase in his salary ($15,000 annually), Cobb would go on to lead eleven houses of worship in the City. His successor, chosen by the Consistory, was Rev. Dr. Edgar Franklin Romig, formerly the pastor of Middle Collegiate Church.

Under Rev. Romig, a greater appreciation for the Dutch language was fostered with the introduction of Dutch sermons. In May 1940, the first Dutch sermon was performed, in response to a demand from members of the community. West End even collaborated with Congregation Shearith Israel because one of the rabbis was from Holland. Dual language sermons continued and in March 1942, the church held a religious service in the 13 languages of the Dutch empire. The less represented languages of the colonies that were spoken ranged from Afrikaans (South Africa), the Papiamento language (Curacao, Frisian), High Malay (Indonesia and Malaysia), and Taki-Taki (also known as Sranan, spoken in Suriname).

The sermon also provided a special prayer, ordered by the Dutch government, for success in the conflict in the colony of the Dutch East Indies, present-day Indonesia. Three months previous, Japan invaded the Dutch territory during the continued conflicts of World War II. Despite prayers, the Dutch East Indies were unable to maintain control of the region.

The incremental growth of the school, which accommodated over 600 students in a space that was built to house around 100, had engulfed the church

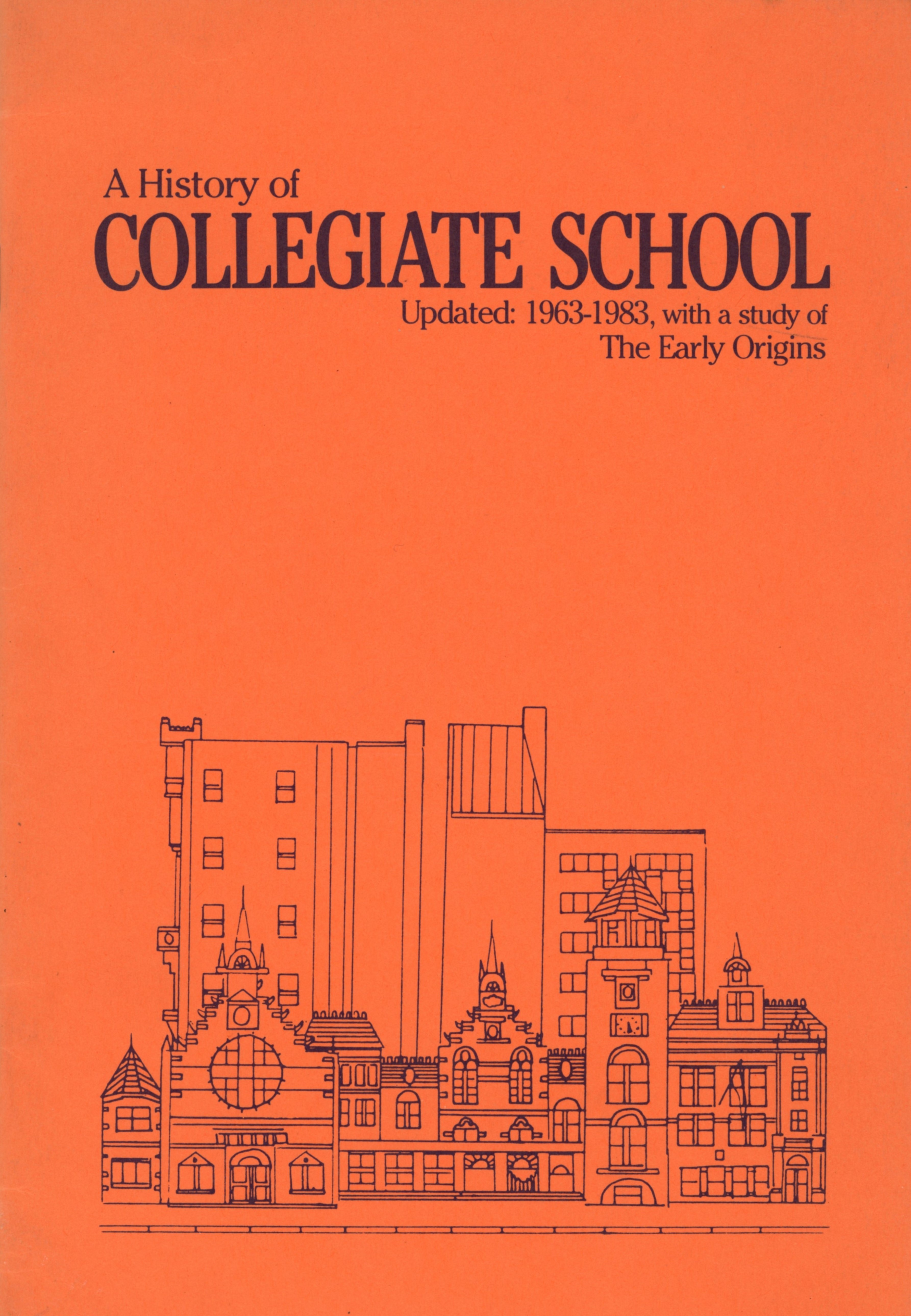

Among the other significant changes that occurred under the leadership of Rev. Dr. Romig, was the official separation of the church from the Collegiate School in the 1940s. The school was established ten years after that of the Reformed Dutch Church (1638) and it is believed to be the oldest private secondary school in the United States. In the 1870s, the Consistory decided to move the school to the Upper West Side. In 1887, they moved into 248 West 74th Street, one of the only former homes still standing, before finally moving into their purpose-built home beside West End Collegiate. The school was co-ed, with many large lecture halls and a spacious gymnasium that both the students and the public could enjoy.

Following separation from the church, the school remained in the narrow wing on 77th Street, but in the 1960s, plans were made to enlarge the footprint of the school on site. The incremental growth of the school, which accommodated over 600 students in a space that was built to house around 100, had engulfed the church. The architect David Todd was commissioned to design an auxiliary school building that would face West 78th Street. Platten Hall, as it was named, was constructed as a 10-story brick and concrete structure that replaced several 1894 Dutch-style rowhouses.

In 2006, the West End church exercised its right to take back space intended for the school. The historic school building remained, but The Collegiate School had until 2022 to vacate and find a new home base. In 2013, they purchased land on West 61st and 62nd Streets between West End Avenue and Riverside Boulevard to build a new purpose-built school. The move was the 17th time since its founding the school relocated within the city, but the first time since 1892. In the place of Platten Hall went a new 18-story residential building, completed in 2022.

The church building suffered some injuries after a fire broke out in December 1982, just days before Christmas. Eight fire companies arrived on the scene, with very little hope the church would survive. One firefighter told the pastor the building was certainly lost, “inside a church, a fire has everything it needs, plenty of wood to burn…and oxygen to feed it.” However, the church was saved, with extensive damage to the roof. The only casualties were the windows, including the large round Tiffany stained glass window, which was pierced by firefighters in order to gain access to a hose. Restoration efforts took many years but campaigns to restore the roof proved successful.

Today, the West End Collegiate church celebrates a wonderfully preserved church, one of the few good examples combining Dutch and Flemish architecture in New York, not excluding two millstones from the original gathering place that live in the vestibule of the church. In 2024, the oldest continually worshiping congregation in New York will share its sacred place with the Church of Latter Day Saints, as they work on renovations of their Lincoln Square home.

References

New York Times, October 25, 1891.

New York Times, November 20 & 21, 1892.

New York Times, November 11 & 14, 1923.

New York Times, August 19, 1927.

New York Times, February 8, 1931.

New York Times, May 18, 1940.

New York Times, March 2, 1942.

New York Times, December 19, 1982.

New York Times, February 5, 2013.

The Collegiate School, A History of the Collegiate School 1638-1963 (1963).

Dunlap, David W., From Abyssinian to Zion (2004).

Hartman, Elizabeth A., Divine New York:Inside the Historic Churches and Synagogues of Manhattan (2022).

West End Collegiate Church, West End Collegiate Church: The First Hundred Years 1892-1992 (1992).

West End Church web site, https://www.westendchurch.org/history.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation and Research Director at LANDMARK WEST!

Building Database

Landmarks Timeline

Explore Houses of Worship

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Learn more about the nonprofit West End Church: