230 Riverside Drive

by Megan Fitzpatrick

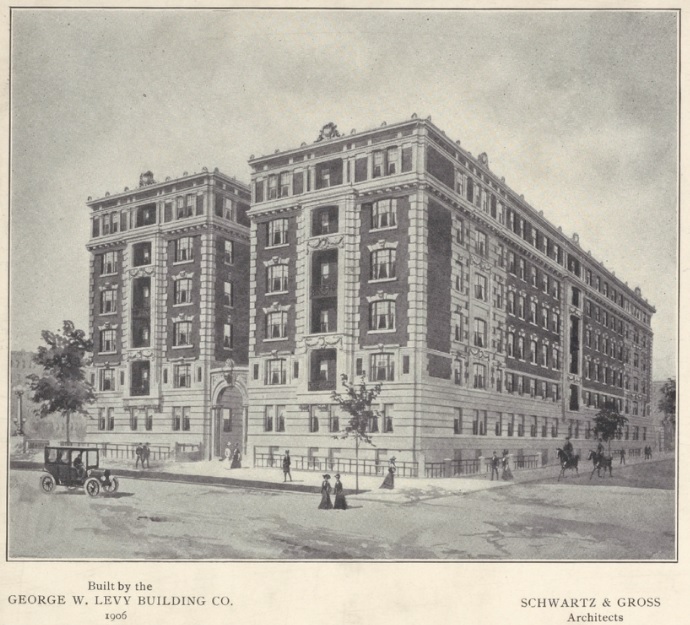

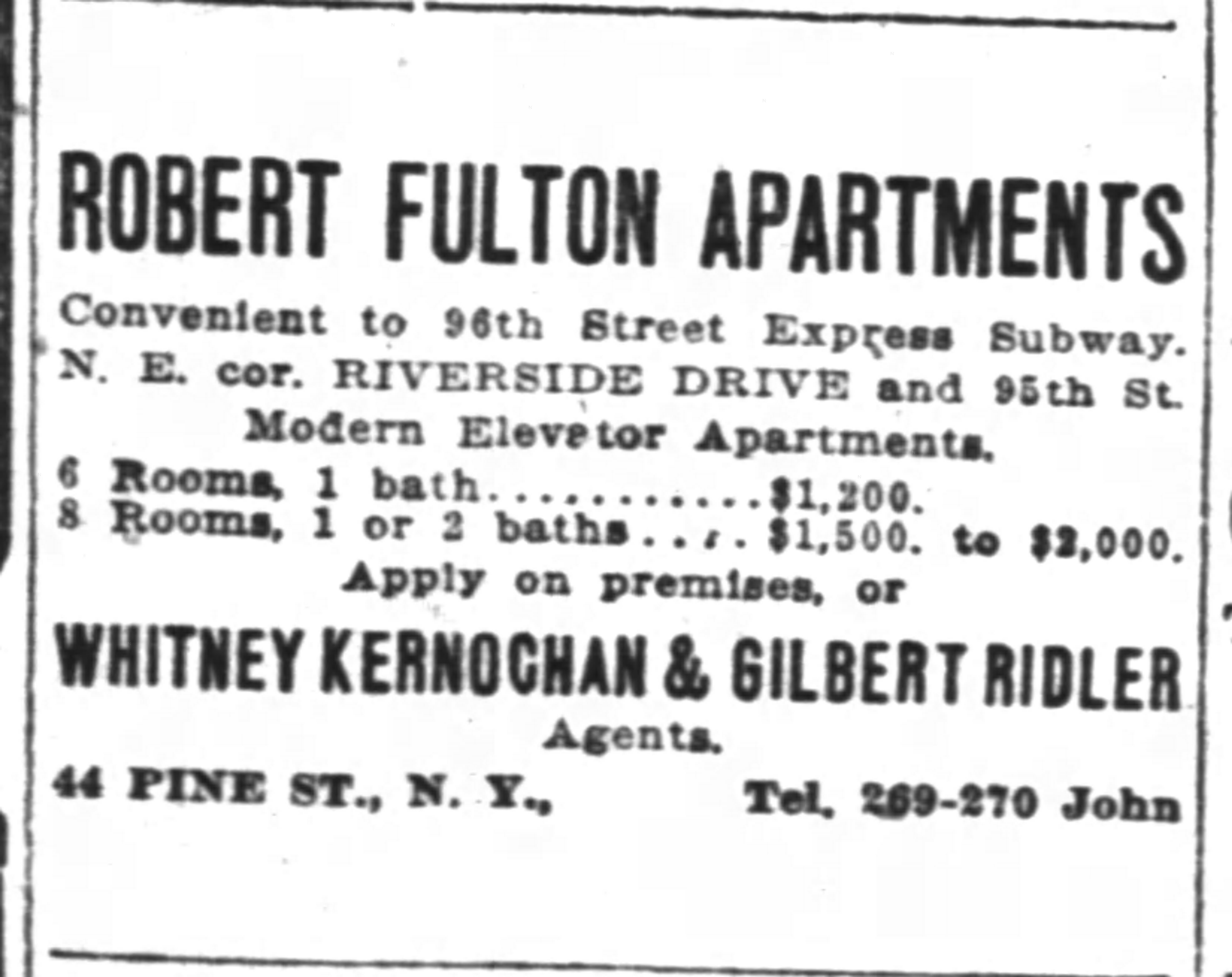

Victorian-era New York apartment houses were falling out of style in the years following World War I, in favor of taller structures with decorative setbacks that tower over the Upper West Side’s skyline. This was the case with Schwartz & Gross’ 6-story apartment house at 230 Riverside Drive named the Robert Fulton Apartments. Built in 1906 by developer George W. Levy, the Robert Fulton was a high-class apartment house adorned with highly decorative terra cotta and featuring two open courtyards and elevator service.

Tenants of the newly built apartments enjoyed views of the most beautiful section of the Hudson. One such tenant was Marie Ogonesoff, who had an untimely death in her apartment days after undergoing a failed abortion procedure by Dr. Julius Hammer, father of American businessman Armand Hammer. This incident led to a sensational trial and Hammer being charged with manslaughter (The Evening World, June 22, 1920).

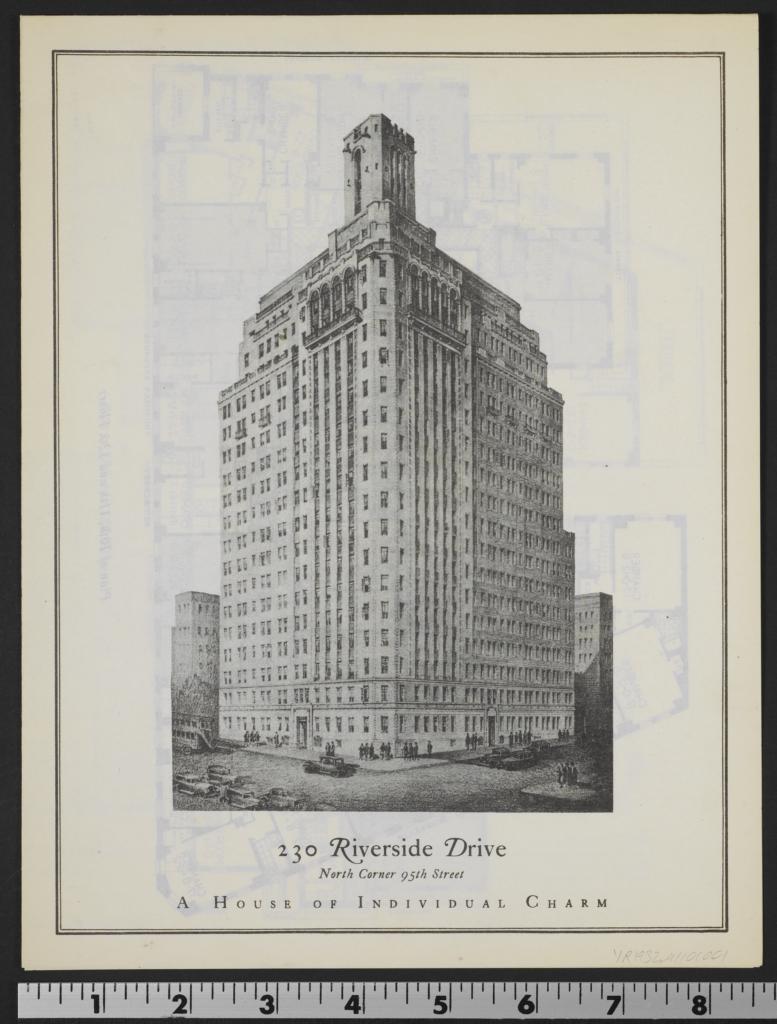

The building was razed in 1930 to build a taller structure in this prime location. Ralph Ciluzzi, the real estate developer of Ciluzzi Construction Corporation, took out a mortgage on the site through the Central Savings Bank on Broadway to build a structure worth a whopping $1,400,000. He recruited Charles H. Lench to design an 18-story penthouse apartment building on the sunny corner of 95th Street. It was one of the first apartments on Riverside Drive to be constructed following the passage of the Multiple Dwelling Law in 1929.

Tenants of the newly built apartments enjoyed views of the most beautiful section of the Hudson

Lench designed a relatively plain building, however, its Medieval Revival Style blossoms above the setback with gargoyles, arcades, and a glass-canopied penthouse. Charles H. Lench was a Canadian-born architect who immigrated to the United States in 1912 and pursued an education in architecture, earning a graduate degree from Harvard. He was an established architect, starting as a staff architect for Bethlehem Shipbuilding Co. before opening his practice in New York, which he maintained until 1940. In addition to his architectural practice, Lench was an author and lecturer on architectural practice and the founder of his own publishing firm, the Architectural Economics Press. At the time of designing 230 Riverside Drive, he wrote The Promotion of Commercial Buildings (1932) based on a series of lectures he gave at Columbia about the relationship of the architect to the promotion of income-producing buildings.

A brochure from 1931 describes the many features of the new apartment that would lure the affluent families of the Upper West Side to it. “A House of Individual Charm” sat on the “sunny corner of 95th Street” boasting its “unusual” proximity to multiple convenient transit options like the express subway station at 96th Street, and advertising its range of room types ready for occupation September 1st, 1931. In 2000, the going rates for an apartment in 230 Riverside Drive (one of only three market rate pre-war rental buildings between 92nd and 96th Street) was approximately $1,800 for a studio and up to $3,400 for a 2-bedroom apartment. (New York Times, Oct. 1, 2000).

The new structure at 230 Riverside Drive, with over 250 units, hosted a number of fascinating and influential people over the years – well-to-do families who wished to take in the serenity of the drive overlooking the hilly Riverside Park and Hudson River. Residents varied from socialites and even criminals to a survivor of the SS Morro tragedy off the coast of New Jersey (Daily News, Nov. 1, 1935; Daily News, Sept. 9, 1934). Significant figures like world-renowned chef Diana Kennedy began her endeavor to introduce the English-speaking world to Mexican cooking in the kitchen of her apartment, which led to her best-selling book The Cuisines of Mexico (1972) (New York Times, July 24, 1996).

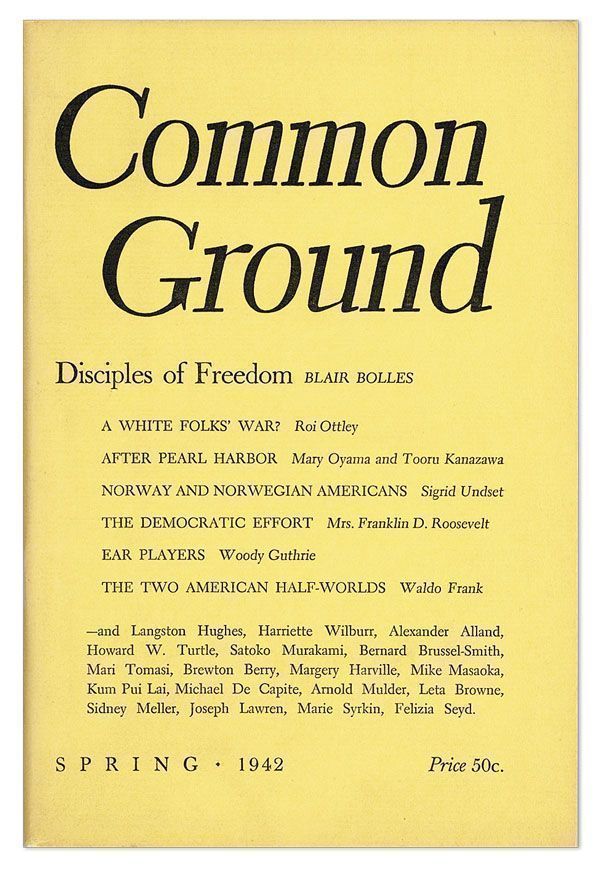

A notable resident was Read Lewis, an attorney and immigrant law expert, who made his mark in New York City trying to help first and second-generation immigrants in the city (Daily News, July 22, 1956). Born in Illinois, Lewis came to New York settled down on Riverside Drive, and began his mammoth career task of trying to tackle the misunderstandings and ignorance surrounding immigration issues. Lewis was the Director of the Common Council for American Unity (CCAU), formerly the Foreign Language Information Service, an organization founded upon those very ideals Lewis wanted to uphold. He launched a magazine called Common Ground, edited by Margaret C. Anderson, who made her name with The Little Review in Greenwich Village.

The magazine, printed during WWII, openly criticized the notion of a homogenous American culture and warned against the dangers of ethnic and religious division, with Lewis stating in the opening issue in 1940 “Never has it been more important that we become intelligently aware of the ground Americans of various strains have in common” (Wall, ‘Inventing the “American Way”’, 2009). A key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes was a frequent contributor to the magazine, even holding a position on the advisory editorial board. Works first appearing in Common Ground were reprinted widely, and from its pages grew directly or indirectly twenty-five books, including Owen Dodson’s Powerful Long Ladder, Woodie Guthrie’s Bound for Glory, Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer, Jade Snow Wong’s Fifth Chinese Daughter and much of Hughes’ work (Beyer, ‘Langston Hughes and Common Ground in the 1940s’, 1991).

Lewis was described as a “cagey, persistent old-stock Midwesterner” with strong ties to the emerging field of social work and a growing reputation as an expert on immigration policy (Beyer, 1991). The organization and magazine failed to make huge waves, with the magazine having an average readership of no more than 8,800, however, Lewis and CCAU staff were consulted regularly by federal government and social service agencies and Lewis aided over 34,000,000 immigrants in his career. He lived in apartment 12H for most of his life.

Diana Kennedy began her endeavor to introduce the English-speaking world to Mexican cooking in the kitchen of her apartment

Jonce Irwin McGurk, an art dealer who was considered the authority on the paintings of Gilbert Stuart, was another notable person who lived in the apartment. He is attributed to building up the art collection of Percy A. Rockefeller, serving as his personal representative, and once reputedly paid $250,000 for a bust of Voltaire. His sudden death came after he suffered a stroke in his bathtub in which he lay, unnoticed, for four days. He was still alive when he was recovered but died some days later (Daily News, Jan. 11, 1947). At the time of his death in 1947, his estate was valued at $20,000, despite owning three extremely valuable sculptures from French artist Jean Antoine Houdon – life-size busts of George Washington, Marquis de Lafayette, and interestingly, the namesake of the former apartment house, Robert Fulton (New York Times, Sept. 10, 1949).

230 Riverside Drive was converted to condominiums in 2004. Some units were renovated “in a more economical sense,” and some units were offered as “do-it-yourself” units. This renovation also involved restoring the structure’s terra cotta under the guidance of conservation architect H. Thomas O’Hara. One of the major changes the building has undergone is the alteration of historic multi-lite steel casement windows at some point before the site was designated as part of the Riverside-West End Historic District Extension II in 2015. Most of the windows are now one-over-one double-hung windows, with approximately 6-10 apartments retaining the original windows.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation and Research Director at LANDMARK WEST!