400 West End Avenue

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Few apartment buildings are graced with the privilege of a name, however, this particular plot on the northeast corner of West End Avenue and 79th street was home to two consecutive blocks of named apartments. On February 7, 1930, plans were filed by owner Abner Distillator and the architectural firm of Margon & Holder, to build an 18-story plus penthouse, apartment that would become The Wexford. Completed in July, 1931 at a cost of $1,500,000 (around $29.4 million today), the high rise would fit in amongst the rising trend of apartment living in the interwar period on the Upper West Side.

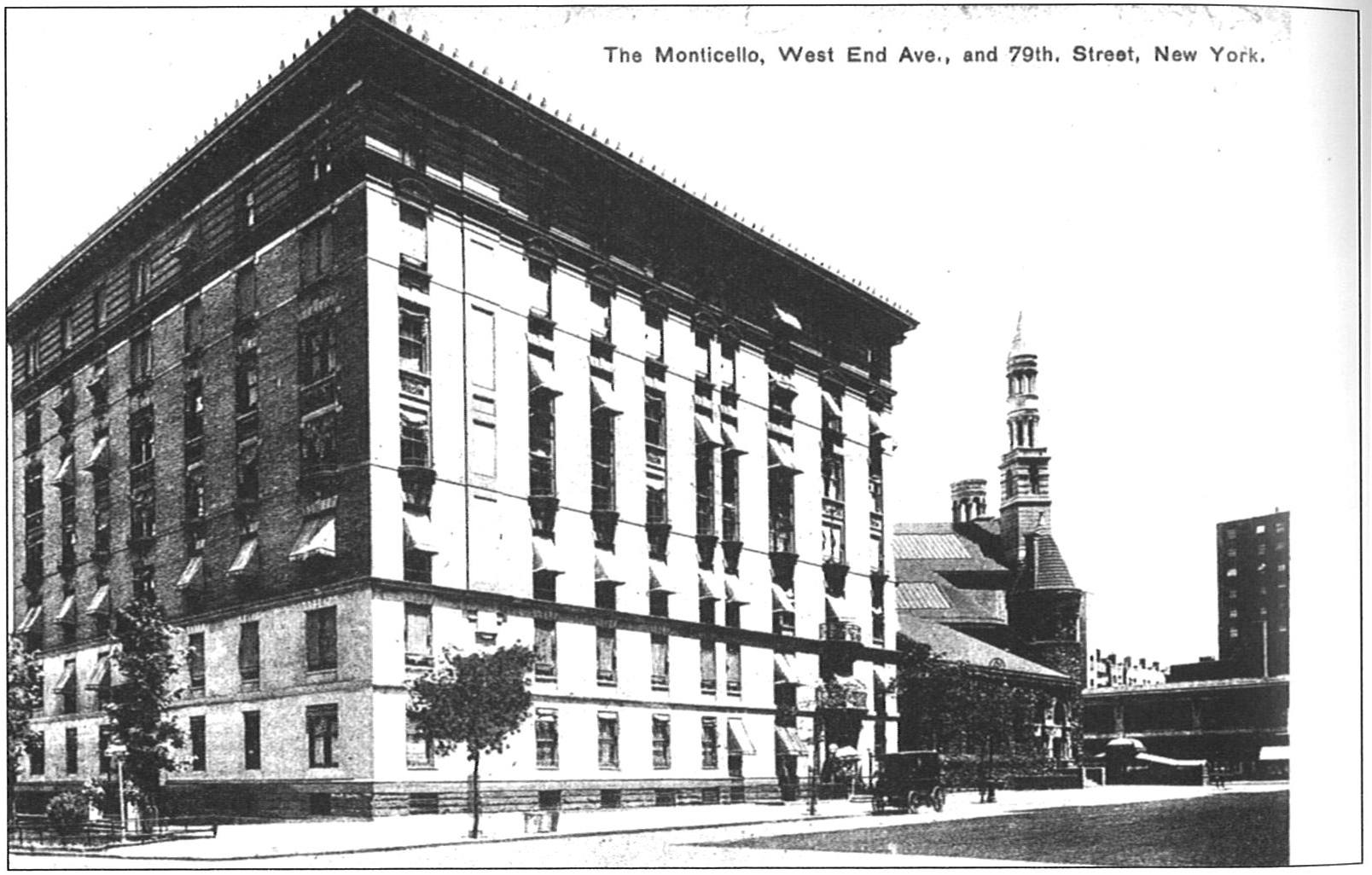

It was common in this period to witness the demolition of rowhouse dwellings to make way for high-rise apartment buildings of 15-20 stories in height, as single-family living was deemed too expensive and apartment living was becoming all the rage. However, before The Wexford took hold at 400 West End Avenue, there wasn’t a rowhouse located there, but a seven-story brick and terra cotta flat, constructed in 1896-97, according to The Real Estate Record and Guide (1 Aug, 1896B, p. 178).

Named The Monticello, this apartment house was designed by William B. Franke, who also designed the 1900 New Century Apartments across the street at 401 West End Avenue. The Monticello, however, did suffer the same fate as many rowhouse dwellings on West End Avenue and was razed in 1930 to be replaced by a larger apartment complex, as did its neighbor at the corner of West 80th street, a ten-story apartment house replaced by George Pelham II’s art deco building, 411 West End Avenue (‘The Upper West Side’ Postcard History Series, M. V. Susi, 2009, p. 96-97).

400 West End Avenue was designed in the Art Deco style, characterized by a two-story cast stone base with pink and yellow marbling, supporting a random raised brick structure, cast stone entrance surround with fluted pilasters and geometric and foliate decorations, and multiple setbacks with decorative cast stone banding. The architectural firm of Irving Margon and Adolph M. Holder, who began their partnership in 1928, is mostly represented in the Upper West Side/Central Park West and Riverside-West End Historic District. The firm is probably best known for the design, with Emery Roth of the 1931 El Dorado Apartments, a designated landmark.

The Monticello, however, did suffer the same fate as many rowhouse dwellings on West End Avenue and was razed in 1930 to be replaced by a larger apartment complex

The character of West End Avenue during this period was largely attributed to be a quiet, fashionable neighborhood and when it goes residential at 70th street, for 35 blocks it has one of the most uniform skylines of any avenue on the Upper West Side, second-only to Riverside Drive. Despite the rapid encroachment of high-rise apartments on townhouses from the 1920s, new builds on West End Avenue and Riverside Drive still contributed to the sense of unity in the district due to the 1929 Multiple Dwelling Law.

Newly constructed apartments were built to the lot lines, many had setbacks that began at the cornice height of older buildings and an Art Deco and Moderne ornamental style was beginning to become the standard for these high rises. In the 1930s, four apartments of 18-20-stories, were constructed on West End Avenue and Riverside Drive by architects Boak & Paris, George F. Pelham, Jr. and Margon & Holder.

400 West End Avenue, with neighbors like the Apthorp, New Century, and Hotel Lucerne, was sure to attract some of the upper crust of New York society. The building could fit 90 families, and apartment leases were in high demand when it came on the market in 1931. Among the first residents were the building’s owner, Abner Distillator, and his family, who lived in 400 West End Avenue for a time until his wife died in 1949 (New York Times, Jan. 11, 1949 p. 31).

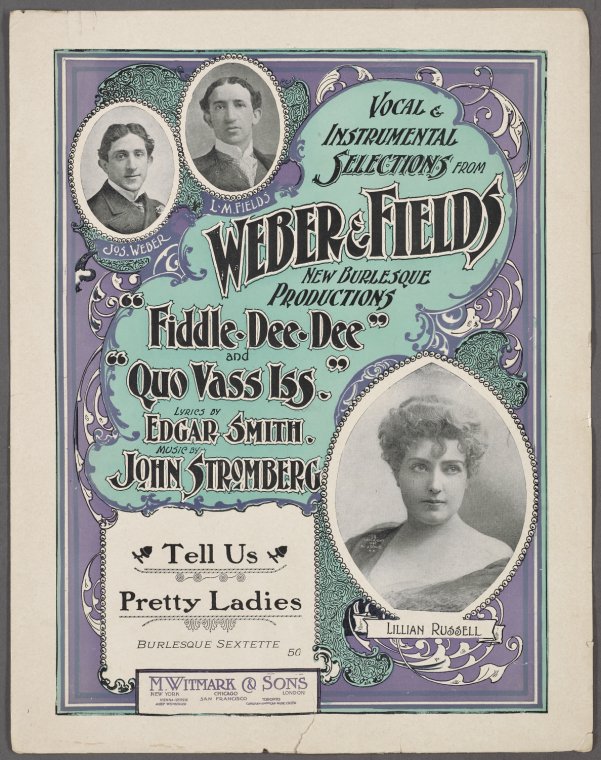

A couple of well-known celebrities took up residence on the avenue soon after construction. Joe Weber, one half of the vaudeville duo Weber and Fields, moved into 400 West End with his wife Lillian Weber around 1933. Both sons of Polish immigrants, Weber and Fields first began performing at the age of nine in the Bowery but found fame in the early 1900s when they took over the Broadway Music Hall with their musical-comedy shows consisting of songs, dance skits and burlesques of popular plays, often collaborating with actress Lillian Russell (Britannica, 2023). The duo claimed they originated the comedy staple pie-in-the-face gag of throwing custard pies into the face of an unfortunate recipient, with the first one ever thrown after they opened their music halls on 1 September 1896. While celebrating his 60th birthday in June 1933, Weber and his wife were injured in a car accident in a taxicab going south on Columbus Avenue and confined to their home at 400 West End resting their injuries (New York Times, Aug. 11, 1933).

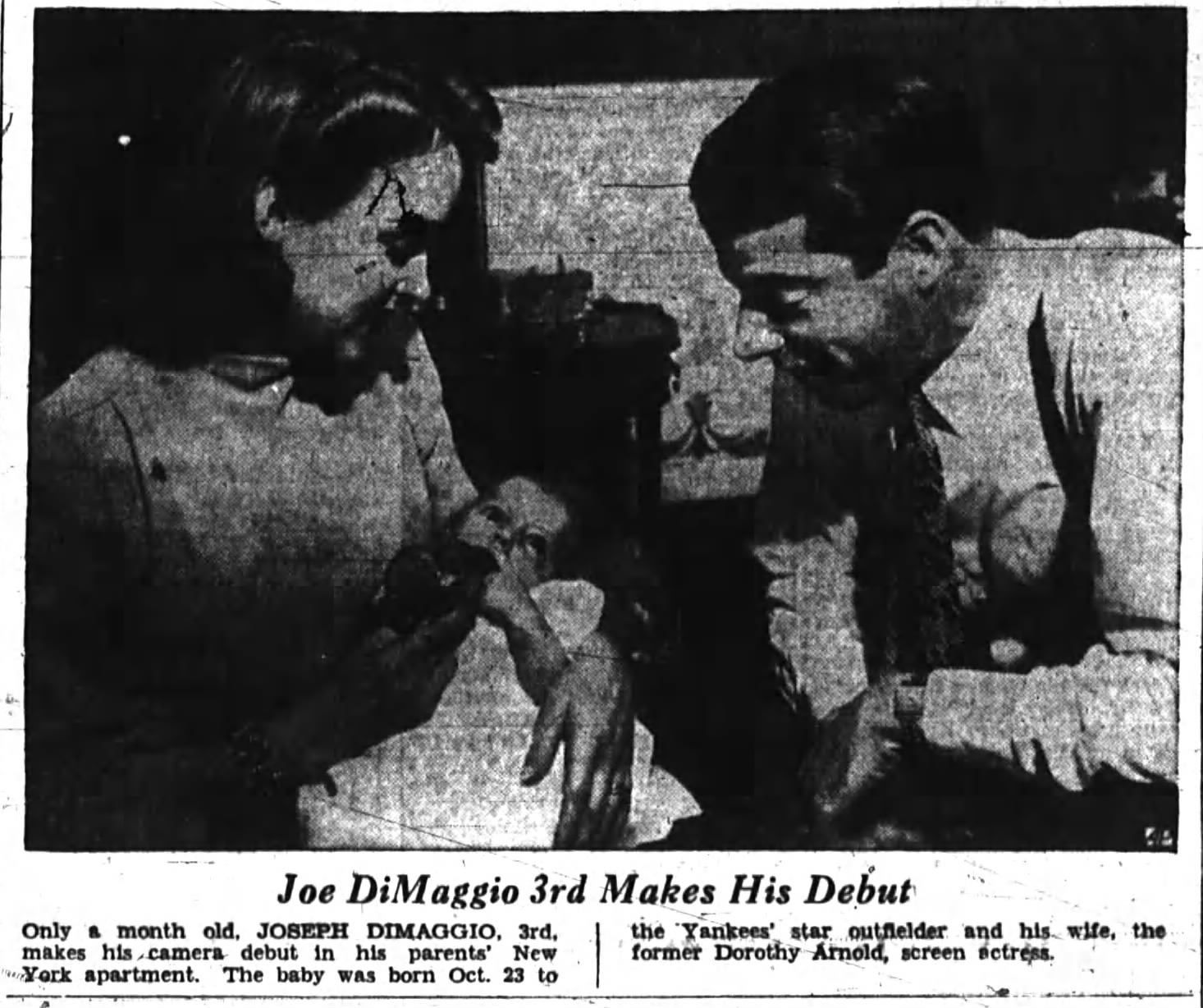

Another famous resident, and probably the most well-known, was Yankees legend Joe DiMaggio, who lived at the penthouse from 1939-1942. DiMaggio’s short time living there was marked by two major milestones, his 56-game streak which earned him a spot amongst baseball legends, and the birth of his son, Joe DiMaggio 3rd (‘Joe D. Slept Here: When a Home Becomes a Sports Collectible’ New York Times, Sept. 20. 2010). A picture published in the Poughkeepsie New Yorker shows the newborn Joe Jr. with DiMaggio and his first wife, Dorothy Arnold ‘in his parents’ New York apartment (Poughkeepsie New Yorker, Nov 25, 1941).

According to author Richard Ben Cramer, of the biography, “Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life”, the DiMaggios were paying $300 per month in rent for their terrace apartment (NorthJersey.com, 2020). DiMaggio wasn’t the only Yankees player on the avenue, Vernon ‘Lefty’ Gomez also leased a penthouse at 825 West End Avenue and it is said that DiMaggio would carpool to the stadium with other players in the neighborhood (New York Times, June 17, 1941, p. 37). DiMaggio even had his own way of signaling to the other players when he was ready to leave for work by standing on the 1,300-square-foot wraparound terrace of the penthouse and waving a towel, according to Mr. Tucker Anderson, who moved into the penthouse in 1995 (New York Times, Sept. 20, 2010).

The children dressed up the vacant room with bunting, a welcome sign, a makeshift table on sawhorses where refreshments paid for by the building management were set and a portable phonograph that played the tune ‘Joltin Joe DiMaggio’ when he entered to meet the 34 enthusiastic fans.

A newspaper article in 1941 highlighted DiMaggio’s gracious side when they reported that a group of children in the neighborhood organized a party in a vacant apartment at 400 West End so they could meet the Yankees legend. The children had been ringing DiMaggio’s doorbell off and on for months in hopes of obtaining an autographed baseball. Apparently, DiMaggio didn’t mind but to solve the situation, the Superintendent George Brook agreed to the suggestion brought forward by four neighboring kids that they throw a party to get their autographs, everyone at once. The children dressed up the vacant room with bunting, a welcome sign, a makeshift table on sawhorses where refreshments paid for by the building management were set and a portable phonograph that played the tune ‘Joltin Joe DiMaggio’ when he entered to meet the 34 enthusiastic fans (Daily News, Oct. 20, 1941, p. 37). ‘Lotta good times in that place’ DiMaggio said about his West End apartment, according to his biographer (New York Times, Sept 20, 2010).

Another Upper West Side haunt for DiMaggio was the now-demolished Mayflower Hotel, built in 1926 just two blocks north of Columbus Circle, overlooking Central Park (currently, 15 Central Park West).

Not only did celebrities live at 400 West End Avenue, so did movie characters. Fredric March, a prolific actor of the 1930s and 40s, starred in the film ‘Middle of the Night’ alongside Kim Novak, in which an apartment at 400 West End Avenue was the location, and central plot point, for the home of March’s character. The film also utilized filming locations on Amsterdam and 84th street, for the home of Novak’s character, as well as Central Park (Daily News, Jan 11, 1959, p. 129).

400 West End Avenue still maintains much of its historic Art Deco facade and is a well sought-after location.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation Director of LANDMARK WEST!