Image Courtesy ininet.org

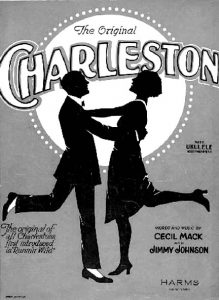

Everybody knows the Charleston rhythm. Most have some idea about the look of the dance. [1]

The Charleston has been filmed in at least a half dozen films and captured in hundreds of photos including an iconic image of Josephine Baker performing the Charleston at the Folies Bergère in Paris in 1925. [2] The woman who first sang the Cecil Mack lyrics for James P. Johnson’s score was Elizabeth Welsh. She later dismissed the lyrics as “dismal.” [3]

Forget the lyrics, she was performing in Runnin’ Wild, a revue that launched an international Charleston dance craze, at The New Colonial Theater on West 62nd Street and Broadway. The show featured Black singers, dancers, and comedians. The New Colonial Theater, built in 1904 changed owners and names many times. When It was razed in 1977, it had most recently been the Harkness Ballet Theater.

After Runnin’ Wild, which ran from October 1923 to May 1934, [4] Elizabeth played in “Lew Leslie’s

Blackbirds of 1928.” [5] But it was in “Love for Sale,” [6] which Elizabeth sang in Cole Porter’s Broadway musical “The New Yorkers” in 1931, that made her a sensation.

Elizabeth Welsh and James P. Johnson took different routes to become international celebrities. Elizabeth was born at home on 63rd Street in San Juan Hill. [7] Her mother was from Scotland and her father was of African and Native American descent. [8]

Elizabeth sang in the choir of St. Cyprian’s Church, went to PS 69 JHS and attended Julia Richman High School. She abandoned her plans to be a social worker for the opportunity to sing. She was recruited from the church choir to sing in Black revues. But, having his daughter become a professional performer was untenable for her strict Baptist father. He would abandon his family, [9] “His parting words were if Girlie’s (his name for daughter Elizabeth) on the boards, she’s lost.”

James was 14 in 1908 when he moved from Jersey City, NJ, with his family to the San Juan Hill neighborhood. Four years later the family moved uptown. Elizabeth pursued her career as a cabaret and musical theater star and Johnson as a composer and performer. But, very early on, it must have been quite a thrill to be part of Runnin’ Wild, a 1923 hit show that was performed right on Broadway and 63rd Street, literally around the corner from where they once lived and she still called home and near the apartment where James had lived with his parents.

The period when Welch and Johnson went to PS 69 coincided with a time when a strong emphasis was placed on music education in the early 20th Century. “The Progressive Movement of the early 1900’s was a time period centered on American evolution and advancement. Within this period of reform, many ‘shared in common the view that government at every level must be actively involved in these reforms’ (West, et al). This included the school system, and eventually resulted in the creation of a music-mandate in the curriculum.” [10]

James valued the exposure to music he gained while still an adolescent. “When I went to Public School 69 I was allowed to play for the assembly and for the minstrel shows put on there. In New York, I got to hear a lot of good music for the first time. Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml were popular, and I used to go to the old New York Symphony concerts. A friend of my brother who was a waiter used to get theater tickets from its conductor (Josef Stransky) who came to the restaurant where he worked. That was when I first heard Mozart, Wagner, Beethoven and Puccini. The full symphonic sounds made a big impression on me.” [11]

Jungles Casino was where James liked to hang out and play piano. What was it like? According to jazzman Eubie Blake, “The place where the real action was in those days was right in the heart of The Jungles (San Juan Hill). One wild place was called Drake’s Dancing Class (on Sixty-second Street) because they couldn’t get a license to operate unless they taught dancing. We called it The Jungles Casino and it was really a beat-up, small dance hall; it was in a cellar where the rain used to flow down the walls. It was so damp down there that they used to try to keep the piano dry by placing lit candles around it. The furnace, coal, and ashes were located right in the same room with the old upright. There were plenty of dancers but no teachers down there. It was some ‘ratskeller.’” [12]

Many of the customers came off the boats that docked in the West Sixties…These people came from around the Carolina and Georgia sea islands. They were called Gullahs and Geechies. These folks worked and played hard; they were able to dance all night after spending the day throwing boxes around as longshoremen…” [13]

Meanwhile, in 1931 Elizabeth headed to Paris where she experienced wild success. Then settling in London, she performed for decades. “During World War II, Welch entertained troops in Britain and joined John Gielgud, Edith Evans, Beatrice Lillie and Michael Wilding entertaining troops in Malta and Gibraltar.” [14]

She was the first Black woman to have her own BBC radio show and she appeared in scores of TV programs. A YouTube video of her singing Stormy Weather in Derek Jarman’s rendition of Shakespeare’s The Tempest conveys her enduring style. [15] She returned to the New York stage in the 1980s performing in Black Broadway and in Jerome Kern Goes to Hollywood, for which she was nominated for a Tony. In his review of the Kern show, Frank Rich of The New York Times urged readers to write their representatives in Congress demanding that she be detained in the United States ”as a national resource too rare and precious for export.” [16]

British writer Stephen Bourne met Elizabeth backstage in London in the 1980s. They became good friends, and Bourne’s biography of her was published in 2005. [17] Hugely informative and admiring of Elizabeth’s life and work, it also contains personal details such as her liaison with Observer publisher David Astor during the height of his mid-20th prominence. Elizabeth admired many fellow performers. Asked in a 1980s interview if she knew Duke Ellington when she was starting out, she responded that at that time, she knew of him, but he was already a big name at the Cotton Club in Harlem. “I was a kid from 63rd Street.” [18]

Bourne was influential in having an English Heritage Blue Plaque [19] installed on the home where she lived in the early 1930s in Kensington, London.

Meanwhile, Johnson’s style had fluctuations in popularity over time but he had an enduring influence in the world of jazz. “Johnson was the foremost proponent of Harlem Stride piano and an absolute master of the keyboard with perfect pitch. Laying the cornerstone of jazz piano before 1920, his Stride keyboard style transformed Ragtime into Jazz, strongly influencing pianists Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Art Tatum and Thelonious Monk.” [20]

Professional Jazz Piano players of the 1920s and 30s were expected to have their own signature style of dressing. James’ wardrobe included “25 suits, 15 pairs of custom-made shoes, two dozen silk shirts, silk handkerchiefs, and a gold or silver-knobbed cane.” [21]

According to the Syncopated Times, “Johnson cut some 55 piano rolls for a half-dozen companies, the finest of their kind. His “Charleston” was the signature tune of the Roaring Twenties. He made hundreds of records for the most important labels of his time, which today confirm his exceptional composing, arranging and pianistic skills that were equal to masters of any musical tradition.

Have a listen: JAMES P JOHNSON_B Charleston, Piano Rolls and Solos 1921-45 [22]

Elizabeth died in 2003. Johnson died in 1995. Considering what it takes to become a star and live up to that reputation, Welch and Johnson had the stupendous talent and drive that won over audiences for decades. And, all this emerged from the turbulent, crowded tenements of West 63rd Street in San Juan Hill.

[1] https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Rc7koNdKRVI

[3] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-jul-19-me-welch19-story.html

[4] https://ininet.org/the-charleston-in-the-1920s-the-dance-the-composers-and-the-re.html

[5] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-jul-19-me-welch19-story.html

[6] IBID

[7] https://biography.jrank.org/pages/2777/Welch-Elisabeth.html .

[8] https://aaregistry.org/story/she-could-do-it-all-elisabeth-welch/

[9] https://amp.theguardian.com/news/2003/jul/17/

[11] https://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/?q=program/runnin-wild-biography-james-p-johnson

[12] https://www.sandybrownjazz.co.uk/TheStoryIsTold/DownInTheJungles.html

[13] IBID

[14] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-jul-19-me-welch19-story.html

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=857Ste6wylM

[16] https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/18/arts/elisabeth-welch-99-cabaret-hitmaker.html

[17] https://www.amazon.com/Elisabeth-Welch-Lights-Sweet-Music/dp/0810854139

[18] https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=8SnHp-r4j3o v=857Ste6wylM

[19] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/elisabeth-welch/

[20] https://syncopatedtimes.com/james-p-johnson-forgotten-musical-genius/.

[21] IBID

[22] IBID