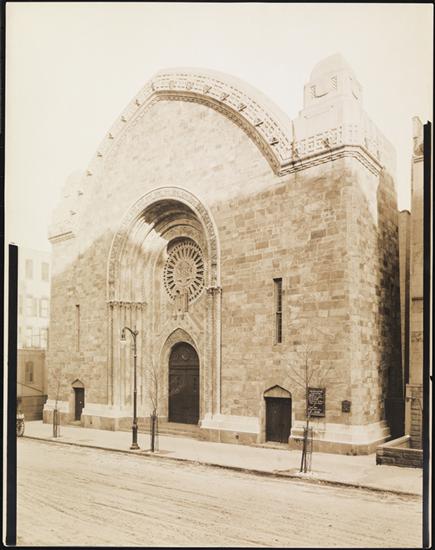

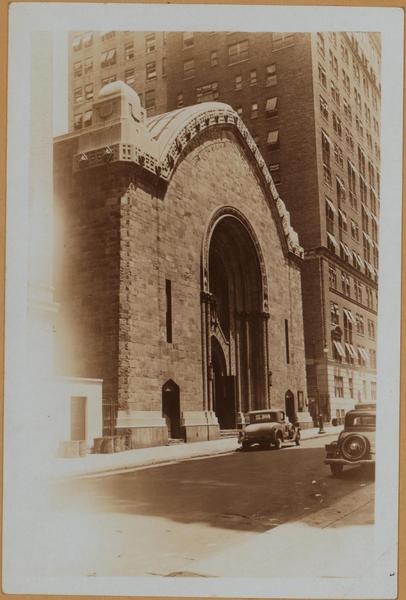

Congregation B’nai Jeshurun

257-265 West 88th Street

by Tom Miller

In the first years of the 19th century Congregation Sherarith Israel, founded by the Spanish and Portuguese Jews who arrived in New Amsterdam in September 1654, was New York’s only place of Jewish worship. When German and Polish immigrants attempted to hold separate services following their native minhag, or rites, they were rebuffed. In response, a group split off, forming B’nai Jeshurun in 1825.

The congregation’s first synagogue was obtained in 1827 when it purchased the building of the First Colored Presbyterian Church (119 Elm Street). It would move three more times (Greene Street, West 34th Street, where Macy’s stands today, and 746 Madison Avenue) before buying land on the Upper West Side in 1917. Each of the former shuls had been architecturally impressive; but this one, on West 88th Street between Broadway and West End Avenue, would be nearly unique.

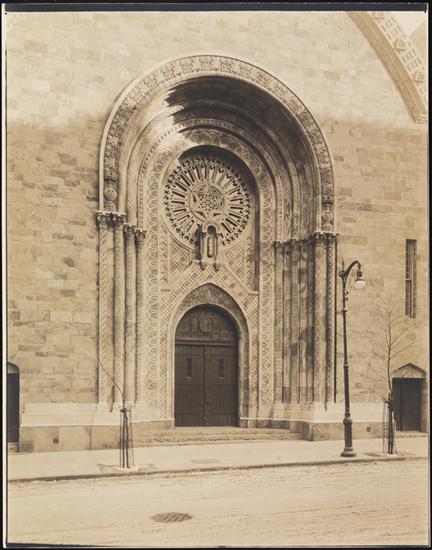

The trustees’ search for an architect went no further than its own congregation. Henry B. Herts and his partner, Walter S. Schneider, were both B’nai Jeshurun members. In seeking to create a style they termed of “Semitic character,” they studied architectural fragments in an effort to establish historically and culturally accurate connections to early Jewish structures.

Ground was broken in 1917 and construction was completed the following year. Scheider & Herts had produced a leviathan edifice that melded Moorish and Middle Eastern elements. The mostly stark façade of variegated, weathered granite blocks provided the backdrop for the dramatic arched portal. Within the soaring arch was a large rose window, containing a Star of David. On either side of the broad copper parapet thickset copper-clad towers rose.

[The Congregation] would move three more times (Greene Street, West 34th Street, where Macy’s stands today, and 746 Madison Avenue) before buying land on the Upper West Side in 1917.

Inside brilliant mosaics, stenciling and tiles echoed ancient Jewish motifs. The main sanctuary was capable of seating 1,100 worshipers.

Congregation B’nai Jeshurun was only unafraid to deal with hot topic issues—like Zionism, Nazism and anti-Semitic discrimination—and its leaders aggressively encouraged debate. On November 22, 1922, for instance, former Ambassador to Germany, James W. Gerard, addressed the congregation about the Ku Klux Klan. He cautioned Jews not to “wage war” on the Klan.

“It would simply increase the very racial and religious antipathies which the Klan seeks to stir up. It is for us [the government] to attend to the Klansmen, and we shall do it. Leave them to us.”

Nearly a decade before Adolph Hitler would come to power in Germany, Rabbi Israel Goldstein recognized the freedom American Jews enjoyed over their European counterparts. On December 25, 1925, he told a group of Jewish college students that they were “more fortunate than their European coreligionists in being able to study in a tolerant atmosphere…In American colleges, the shadow of discrimination may not be altogether missing, but if there be a lurking prejudice against the Jewish student it is covert and not overt.”

Of the hundreds of funerals held here, one of the most visible was that of shoe dealer and importer Israel Miller on August 21, 1929. A Polish cobbler, Miller had arrived in New York City in 1892 at the age of 19. His inventive designs caught the eye of theatrical producers and performers and within just three years, the I. Miller shoe business was a success. By the time of his death, I. Miller shoes had a string of stores in Manhattan and Brooklyn, including its Times Square building adorned with full length marble statues of actresses. Newspapers reported that more than 2,000 mourners attended Miller’s funeral and hundreds more, unable to get into the synagogue, crowded the streets.

The anti-Semitic discrimination in Europe, which Rabbi Goldstein had mentioned nearly a decade earlier, was brutally evident in 1933 following Hitler becoming Chancellor of Germany. On November 30 Charles H. Sherrill, former Ambassador to Turkey, addressed the congregation regarding the proposed ban of the Berlin Olympics.

As James Gerard had done, he cautioned against stirring up trouble. The New York Times reported, “Although the treatment of Jews in Germany was ‘outrageous and hideous,’ General Sherrill said, a boycott against the Olympic Games there would be a worse thing.” He suggested that the backlash might even be felt at home. “It would provide an ‘anti-Semitic feeling’ in the United States,” reported the newspaper.

After the United Nations voted to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, a service “of prayerful thanks for the Jewish state” was held in B’nai Jeshurun on December 6, 1947. The speakers reflected immense optimism, blissfully unaware of the decades of turmoil to come.

Moshe Shertok, Director of the Political Department of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, told the congregation that the Arab masses “want to live in peace with the Jewish people because they know that a Jewish state will bring great benefits to the Arabs.”

Rabbi Israel Goldstein was a bit more realistic. “We are fully mindful of the difficulties which still lie in the path and of the gap between the formal decision and the actual fact. But we face the future with faith.”

On November 30 Charles H. Sherrill, former Ambassador to Turkey, addressed the congregation regarding the proposed ban of the Berlin Olympics. As James Gerard had done, he cautioned against stirring up trouble.

B’nai Jeshurun’s tradition of political and social involvement was evident in 1978 when it staged a series of lectures entitled “Dialogue ’78.” Among the speakers were Rabbi Irving Greenberg, described as a “Jewish thinker and spiritual guide” who spoke on the Holocaust; Shimon Peres who would go on to become Israeli President and Prime Minister; and Emil Fackenheim, “one of the world’s leading philosophers.”

In May 1991, the imposing synagogue was threatened when the roof collapsed, burying part of the sanctuary under a half-ton of debris. Services moved to the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew and after a five-year restoration and renovation project, the results were a modernized, multiple-use space.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com