By Claudie Benjamin

By Claudie Benjamin

Suffering from an infected tooth on the pre-antibiotic Upper West Side of the 1920s, you needed to find a dentist, so it was reasonable to anticipate an extraction. The option of Google searches for biography, ratings, and reviews was nearly 100 years in the future. You very probably would go to a neighborhood dentist on the recommendation of friends or acquaintances, or phonebook search sans unavailable background checks.

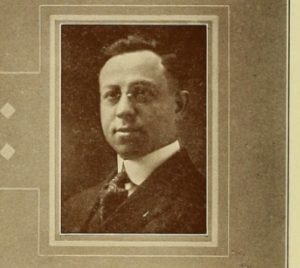

Jacob Gross, a 1919 graduate of the College of Dental and Oral Surgery (later merged with Columbia University), worked at the General Post Office before building his practice on the 2nd floor of 29 Columbus Avenue, just a few blocks south of San Juan Hill. And, as reported in The New York Times on October 29, 1927, he drew his practice from Black patients who lived in “the Hill.” (1)

The New York Times also reported another connection with San Juan Hill, a woman who claimed Dr. Gross had fathered her baby girl, giving San Juan Hill as her address. According to reports, the baby was cared for by a woman who also resided at 246 West 63rd Street. In these pre-DNA profiling days, a paternity suit brought against Gross in 1922 was dismissed for lack of evidence.

The dentist was earning an inordinately large amount of money and depositing an average of $200-$300 a day (almost $4,000 in 2025) in the Columbus Circle Manufacturers Hanover Trust bank–a lot of money in those days.

This all ended when Dr. Gross was murdered in his dental office on October 28, 1927. The event was described in lurid detail by The New York Times in what today would be considered gumshoe pulp fiction style. Detectives scanned the crowd for suspects at his funeral, which several hundred Masons attended. Bella, the dentist’s wife, prostrated with grief, had to be supported as she entered the building where services were held.

College of Dental and Oral Surgery of New York, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine, Columbia University School of Dental and Oral Surgery. The Codos: Yearbook of the College of Dental and Oral Surgery of New York.

Although Gross was known to be in his office in the morning, he never saw patients before 1:00 pm. Detectives on the case were unable to figure out how he was spending those mornings. According to the Times, there was some unsubstantiated speculation that he was dispensing alcohol for non-medical purposes.

Various clues gathered by the detective led nowhere. Two years before his death, for example, Dr. Gross took out an insurance policy with a clause that specified double indemnity should he succumb to a violent death. Other dead-end leads and random, inconclusive clues included evidence that the dentist was nervous, as his fingernails were bitten to the quick. Though he was wearing a two-carat diamond ring on his left hand and carrying a wad of bills, nothing appeared to have been stolen.

His widow said she had no knowledge that he had been practicing as a dentist and thought he was still working at the General Post Office, where he had only worked during a period between completing his professional training and beginning a dental practice seven years earlier.

Two years after the murder, salesman Hyman Hirsch, alias “Sam Rosen,” was apprehended in Coney Island. It emerged, according to his confession, that the crime, which also involved two accomplices, had not been related to Gross’s double life but that his name was targeted for the burglary/murder after having been randomly selected from a phone directory. Whether this was true or if Gross had enemies who had contracted the hit will never be known. A whiff of suspicion lingers when reading another Times article describing the testimony of the chauffeur who drove the murderer and his accomplices to Columbus Avenue, since police were alerted to this man’s involvement through a contact in the underworld. (2)

Hirsch was tried for murder in 1930. The verdict was first-degree murder. However, in January 1931, days before Hirsch was scheduled to die in the electric chair, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was then the Governor of New York, commuted the Sing Sing inmate to life imprisonment. (3)

In the earliest of multi-year reporting, the detailed description of the murder scene in the newspaper invites contrast with some ways in which dental practices have evolved. The second-floor location of dental offices (marked with a sign in the window was prevalent in the Upper West Side).

The electrician who maintained an office in the same building as the dentist’s office discovered the body of the murdered man. In the Times account, the man recalled that he called out to Dr. Gross and assumed he was not heard because of the rumble of the 9th Avenue El train that passed just by the building. “He walked into the office (with its) worn plush sofa, dog-eared magazines, a strip of ancient rug, and the murmuring swing of a tall clock’s pendulum. (He) went to the middle of one of three booths containing dental chairs. “Say, doc, did anybody…” he began, and then halted, for he had seen a shiny shoe curved awkwardly on the floor.” (4)

Dentists’ offices only started taking on a tasteful, decorator look, often at upscale addresses, beginning in the 1970s – think comfortable couches and chairs in the waiting room, as well as sophisticated works of art on the walls. And, in the examination room, streaming video images of mountain and seaside landscapes, mellow jazz playing softly, and increasingly innovative space-age scanning equipment. Today, we are far from the bleak, utilitarian patient chairs and white porcelain spittoons characteristic of early dental offices. Until at least the late 1960s, dental equipment often included threatening-looking clinical dental instruments that made loud noises during treatment, the use of uncomfortable cardboard wedges inserted into a patient’s mouth to take X-rays, and the liberal use of morphine. These days, “according to the American Dental Association endorsed guidelines, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are more effective at reducing pain than opioid analgesics, and are therefore recommended as the first-line therapy for acute pain management.” All changes that came too late for Bella, and Dr. Gross.

Photo Credits:

Tax Photo of 21 Columbus Avenue, Credit: New York City Municipal Archives.

Jacob Gross DDS, Credit: College of Dental and Oral Surgery of New York, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine, Columbia University School of Dental and Oral Surgery. The Codos: Yearbook of the College of Dental and Oral Surgery of New York.

References:

1)

2)

3)

4)