Union Baptist Church

by Jessica Larson

In 1904, Union Baptist Church constructed its second building at 204-206 W. 63rd Street, adjacent to its previous location at 202 W. 63rd Street. Designed by architect James Riely Gordon, most known for his Texas courthouse buildings, at a cost of $75,000 (about $2,496,700 in 2022 dollars), this new church was remarkably ambitious. It consisted of three stories and a partial basement was constructed with brick and terracotta and included a large stained-glass window on the façade.

The original plans show that a library and pastor’s study flanked the entrance on the first floor, which also contained gender-segregated bathrooms and two dressing rooms on either side of a platform at the rear of the building. This first floor was likely used for social functions such as meetings or Sunday school instruction. The church often held fundraising events, such as dinners, which would have been located in this room. The church’s pulpit and probably some seating would have been located on the second floor, with additional seating primarily located around the third-story balcony. Gordon’s plans show that originally a larger stairway entrance was intended; this was eventually downsized in construction.

[Reverend George Sims was] “the “leader of San Juan Hill.”

Until the construction of St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church’s purpose-built mission building in 1907, Union Baptist was the most significant social and religious center in San Juan Hill; like many contemporary Black churches, Union Baptist worked to fill welfare services that white charitable institutions would not extend to Blacks. In addition to the childcare services that were offered at Union Baptist’s neighboring building at 202 W. 63rd Street, the church’s founder and reverend George Sims was, as the Black newspaper the New York Age phrased it, the “leader of San Juan Hill.” In line with the Social Gospel movement of the early 20th century, Sims approached his religious work as inseparable from his duties towards the poor in San Juan Hill. As one prominent reformer, Mary White Ovington, stated, “When [Sims] talked of Christ from his pulpit, Jesus became alive, a workman, a carpenter who took off his apron and went out to answer the call to preach.”

Sims and Union Baptist were active in many activities not strictly related to religion. In 1905, following a riot in San Juan Hill caused by the police’s persistent brutalization of the neighborhood’s Black residents, Sims acted as a liaison between the police and the interests of the Black community. As white philanthropists were funding the construction of San Juan Hill’s four model tenements for Black renters–the Tuskegee, the Hampton, and Phipps Houses No. 2 & 3 –Sims and his congregation made efforts to foster Black-directed business efforts in property ownership and management. In 1906, Sims began the Sims Union Realty Company in the hopes that the venture could serve as both a solution to the church’s debts as well as a provide a Black-run alternative to tenants, who had long been exploited by the city’s white landlords. For $5, Union Baptist congregants could purchase one share in the company. That same year the Sims Union Realty Company purchased four tenement buildings on West 64th Street and two on West 61st Street; these tenement buildings included three-room arrangements and were newly decorated by the company.

These business ventures prefigured the later real estate success in Harlem of St. Philip’s Episcopal and Philip Payton’s Afro-American Real Estate Company. Union Baptist frequently collaborated with other institutions on West 63rd Street, including the Children’s Aid Society’s Henrietta Industrial School and St. Cyprian’s Church. Sims and St. Cyprian’s Rev. Johnson publicly called for neighborhood residents to use milk stations, the two organized a committee to address police violence against Blacks in 1917, and the two churches, despite being of different denominations, frequently collaborated in fundraising efforts.

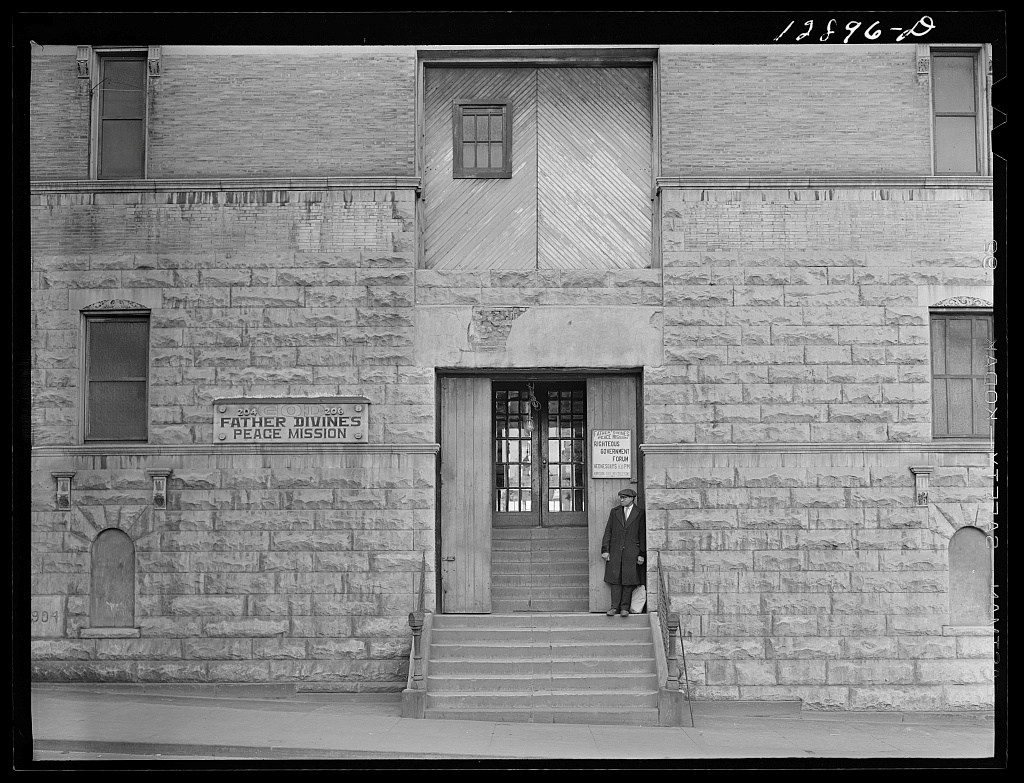

In 1926, Union Baptist followed the migration of Manhattan’s Black community and reestablished their congregation in Harlem at 240-252 West 145th Street, though the church retained their West 63rd Street properties and continued to offer services in San Juan Hill for a time. Still headed by Sims, the church purchased the Harlem site for $90,000 (about $1,506,500 in 2022 dollars), on which already existed a theater with 7 adjoining commercial spaces; these buildings were renovated several times over the years to be used as a church. At some point, likely around 1937, the West 63rd Street church was either sold to or simply used by the Father Divine Peace Mission, a Black-dominated religious movement that was prominent in the U.S. in the mid-20th century; the building was used as what the movement termed an “Extension Heaven” –communal living spaces where residents could pay a small fee for food and sleeping accommodations. Demolition to make way for NYCHA’s Amsterdam Houses over the site began in September 1941.

Union Baptist followed the migration of Manhattan’s Black community and reestablished their congregation in Harlem

Resources:

Dunlap, David W. From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide for Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. Columbia University Press. 2004.

The New York Age (New York, NY)

March 4, 1907, p. 18.

November 12, 1908, p. 3.

November 15, 1906, p. 6.

January 9, 1913, p. 5.

October 30, 1926, p. 1.

August 4, 1945, p. 6.

Mary White Ovington, Black and White Sat Down Together: The Reminiscences of an NAACP Founder, ed. Ralph E. Luker (New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1995 (reprint)), 28.

“Police Accused of Inciting Race Riots.” New York Time. July 20, 1905: p. 12.

“’San Juan Hill’: Its Colored Church, with a Mortgage That Needs Lifting.” New-York Tribune. July 2, 1906: p. 4.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, January 4, 1919, v. 103, no. 20, p. 660.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, April 9, 1904, v. 73, no. 1882, p. 791.

Jessica Larson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also the Joe and Wanda Corn Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum & National Museum of American History