Multiple Losses in Red Ink

by Tom Miller, for The Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In March 1892, architect Francis A. Minuth simultaneously filed plans for a five-story brick flat, or apartment house, on the southeast corner of Columbus Avenue and 84th Street, and three architecturally harmonious five-story flats adjoining it, at 487 through 491 Columbus Avenue. Erected by developer John Casey and completed before the year was up, the latter three structures were designed in a balanced A-B-A configuration, their yellow brick facades highlighted with limestone accents. The middle building, 489 Columbus Avenue, distinguished itself from its siblings with arched openings at the third and fifth floors, and exuberant stone voussoirs above the second-floor windows. The three structures cost Casey the equivalent of just over $1 million today to erect.

Each of the addresses had a store at ground level. The Colonial Bank opened a branch in 487, Bernhard Meyer’s furniture store was in 489, and 491 became home to Andrew Lemon’s grocery store. There were three apartments per floor in each building, and they filled with a wide variety of tenants—actresses, teachers, office workers, architects, and brokers.

Among the initial residents of 487 Columbus Avenue were William Hastings and his wife, Mabel. Hastings was a clerk in the City Tax Office. The couple had married in 1887. Mabel was a 21-year-old widow at the time, while the groom was 57. Before their marriage Mabel worked as a domestic. The Press revealed, “She had always been more or less addicted to drink, and her husband had repeatedly remonstrated with her about it.”

And so, when Mabel left to go shopping at 2:00 on August 9, 1894, and still was not home late that night, William was understandably concerned. Then, shortly after midnight, he heard a feeble cry for help from outside the door. He found Mabel on the staircase. “Get me upstairs, Willie,” she whispered, “I am dying.”

When he asked what had happened, she showed him her broken umbrella, and said “I have been attacked, but I drove him off with my parasol.” Suspecting that he was getting only part of the story, William asked if she had been drinking. The Press reported, “she answered that she had taken a drink with a woman she knew and thought the drink may have been drugged.” William got her to the apartment, and then called for a doctor. Before he arrived, Mabel was dead.

On Christmas Day, 1896, The Evening Telegram reported that “Madame Alice Sterling” had been arrested for “keeping a disorderly house,” the polite term for a brothel.

An investigation was launched. The Press said, “The police scoff at the story that she was attacked and attribute her trouble to an entirely different cause.” Victorian discretion assumed that was information enough for the public. However, it was determined that instead of going shopping, Mabel had gone to Koster & Bial’s music hall. There, according to the newspaper, “she had met another woman and a man.” The Lockport Daily Journal added, “A gold ring, evidently the property of a man, was found in her pocket. Mr. Hastings knew nothing of the ring.” An autopsy showed no foul play, nor any evidence of an assault.

Living next door at 489 Columbus Avenue in 1896 was Edward MacArthur and his mother. They rented a room to Henry J. Zimmerman. But trouble came on July 16 when Zimmerman said something unseemly to Mrs. MacArthur. It earned him a punch in the face. Zimmerman had Edward MacArthur arrested for assault. In court the following day, the young man explained himself to Magistrate Mott. “I merely defended my mother’s honor,” he concluded. The judge was sympathetic. “You did right to stand by your mother, and I discharge you.” MacArthur was released and, one assumes, Henry Zimmerman found new lodgings.

Actress Louise Muller returned home to 487 Columbus Avenue on May 21, 1897 to find a young man in her apartment.

“How did you get here?” she asked.

“I came to see Miss Muller,” he answered, sidling towards the door.

“Well, you see her; what do you want?”

“I guess I made a mistake,” he answered and bolted downed the stairs.

Louise Muller was not about to let him escape. She was on his heels, yelling, “Stop! Thief!” One pedestrian after another joined the chase, until there was a sizeable crowd in pursuit. A policeman nabbed 20-year-old Michael Kelly, who, at the station house, was found to be an applicant for an appointment as a police officer. His alibi was hard to believe. The Sun explained, “he said he had no intention of stealing anything, but had gone to the home of Miss Muller to see if she wanted her furniture insured. He said his brother was an agent for an insurance company.” He was charged with unlawful entry into a building.

Trouble came to the apartment of Alice Sterling in 491 Columbus Avenue later that year. On Christmas Day, 1896, The Evening Telegram reported that “Madame Alice Sterling” had been arrested for “keeping a disorderly house,” the polite term for a brothel. The article noted, “She has been keeping what she terms a massage establishment at No. 491 Columbus avenue.” The following day, Alice had a lawyer “and several well dressed men” in court to defend her. They declared, according to the New York Herald, “that the prisoner and the two women who were employed in her establishment as assistants were entirely respectable, and that the arrest was an outrage.” One customer, who refused to give his name, added that “massage was perfectly recognized as a therapeutical agent.” The New York Herald reported, “Magistrate Wentworth believed the evidence submitted by the police to be strong enough to hold Mrs. Sterling.”

In 1893 chemist, Robert M. Lewis married Mary Estelle Grunert. Because she was significantly younger than her 54-year-old husband, her parents disowned her. The newlyweds moved into 489 Columbus Avenue. Lewis developed a process to manufacture red ink inexpensively, and The New York Herald said, “He found no difficulty in selling this ink to banks, lawyers and insurance companies.”

The Lewis’s marriage ended abruptly with a quarrel on November 11, 1896. Mary told the building’s janitor, John Russell, “I had my first quarrel with my husband today. He flew into a rage and ran to the bathroom where he had a hemorrhage that killed him.”

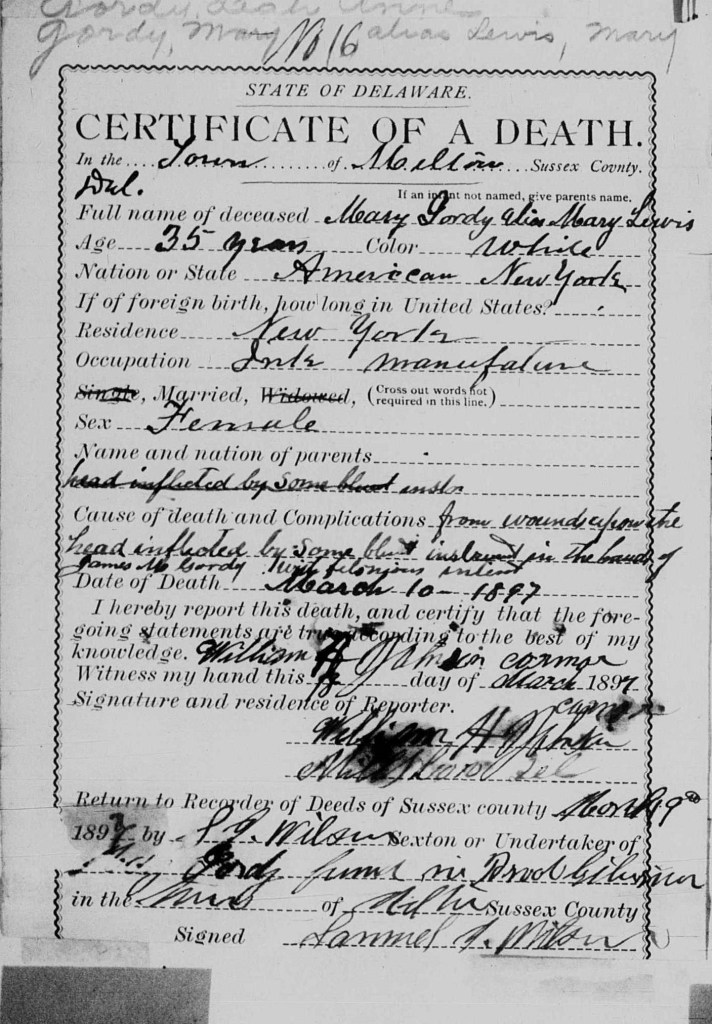

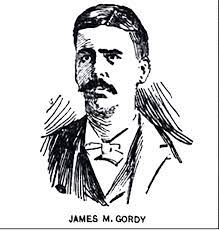

Mary moved to 306 West 139th Street shortly afterward. She advertised for a buyer for the patent of his ink process. She was contacted by James M. Gordy, who offered to buy the process. Within a matter of weeks, he had convinced her to marry him, and she agreed to move to his Delaware farm. It would be a short-lived romance. Unknown to Mary, Gordy was already suspected of having killed his first wife, Sarah Pennewill Gordy, and his brother, Peter B. Gordy only months earlier.

On March 19, 1897, a few days after the wedding, Mary arrived by train in Milford, Delaware. Instead of taking her to the farm, Gordy drove the carriage to the Broadkill River, took his bride to a secluded spot in a small boat, then bludgeoned her with an oar. He dumped her body into the river and left the scene. A month later, on April 16, The New York Times reported that he had been convicted of murder in the first degree.

Around 1897, Siegler & Co. liquor store opened in 489. In 1899 the store at 497 was home to Henry L. Wolf’s silverware store. John Power, who lived in 489 Columbus Avenue, was employed by Wolf. On the night of June 9 that year, thieves entered Wolf’s store through a rear window. Three nights later they returned, entering the same way. They made off with $700 in silverware in the two burglaries.

Suspecting they might hit the store again, detectives had Henry Wolf place a valuable set of silverware in the window. They then waited. Sure enough, two nights later at 2:00 a.m. two men clambered through the window. They became alarmed, however, and fled. A detectives saw one of the perpetrators bolt into 489 Columbus Avenue. A few minutes later a young man sauntered casually out, and said to Detective Donahue, “I guess Wolf’s store has been robbed again.”

The Sun reported, “five babies between the ages of six months and a year old and as many mothers were rescued by way of a fire escape…Firemen Strubel, Florence, Miller and Connors…made their way up the escape and handed down baby after baby. The mothers followed and the firemen were nearly smothered with baby clothes and lingerie.”

Donahue replied, “Yes, and you seem to know so much about it that I’ll arrest you.” And, indeed, he did know much about it. He was John Power, Wolf’s clerk who had repeatedly left the rear window unlatched.

On the night of January 14, 1908, fire started in a baby carriage under the ground floor stairs in 489 Columbus Avenue. It spread so quickly that no one could escape by the entrance. The Sun reported, “five babies between the ages of six months and a year old and as many mothers were rescued by way of a fire escape…Firemen Strubel, Florence, Miller and Connors…made their way up the escape and handed down baby after baby. The mothers followed and the firemen were nearly smothered with baby clothes and lingerie.”

Mrs. Max Steiner, who had left her children alone, returned home to see the commotion. Although her children had been rescued, she “couldn’t believe they had been saved and fought with the firemen until dragged away. She kicked a large electric sign in front of the store of Siegler Bros., wholesale liquor dealers, at 489 Columbus avenue, and it fell to the pavement with a crash.”

Happily, no one was seriously injured. The fire, which was confined to the hallway, did an estimated $72,500 in damages by today’s standards.

Columbus Avenue experienced great changes in the third quarter of the century. In 1982 Handblock opened in 487. The store sold Indian print cotton sheets, tablecloths and napkins, and other household textiles. It was replaced by the Canadian-based boutique April Cornell in 1995. The store next door at 489 was home to The Hero’s Journal by 1991, described in New York Magazine as offering “a wide variety of unusual, affordable gifts.” On September 6, 2011, The New York Times food columnist Florence Fabricant reported on the upcoming opening of Gastronomie 491, “a well-rounded fancy food shop and café.”

More recently, Unique Boutique, a vintage clothing store, moved into 487, Ashoka, an Indian restaurant is in 489, and in 2021, Noi Due Café opened in 491 Columbus Avenue.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

487-491 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 487-491 Columbus Avenue: