Fire, Films and a Fraud

by Max Chavez, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

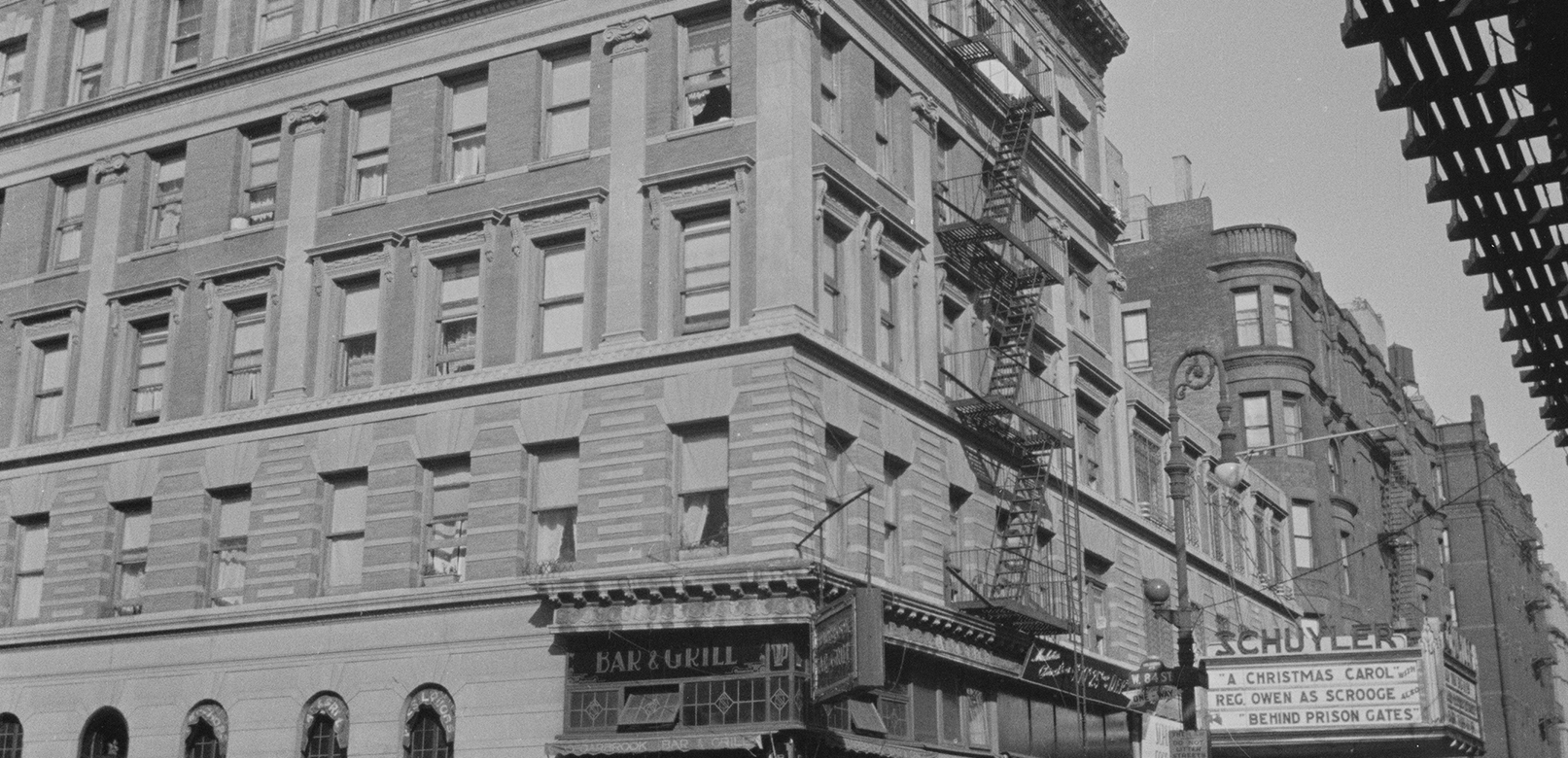

The five-story building at the southwest corner of Columbus Avenue and 84th Street was designed by firm Neville & Bagge and opened to the public in 1895. George A. Bagge and partner Thomas P. Neville were quite successful in New York City, having established their joint practice three years earlier in 1892. The duo continued to design buildings together up until the end of the 1920s, mostly in the Renaissance Revival style seen at 504 Columbus Avenue. Their flats can still be found throughout Manhattan with many concentrated in the Upper West Side. The building is stately but without ostentatious adornment, its most notable ornamentation being the Ionic pilasters stretching along the top three stories and the pleasant Vitruvian wave beltcourse dividing the building’s second and third floors.

Another tenant was May Atzbach who made waves when she was reportedly cured of her deafness onstage by Darius Wilson, M.D., a physician who proclaimed himself to be the greatest aurist of his (or any) time.

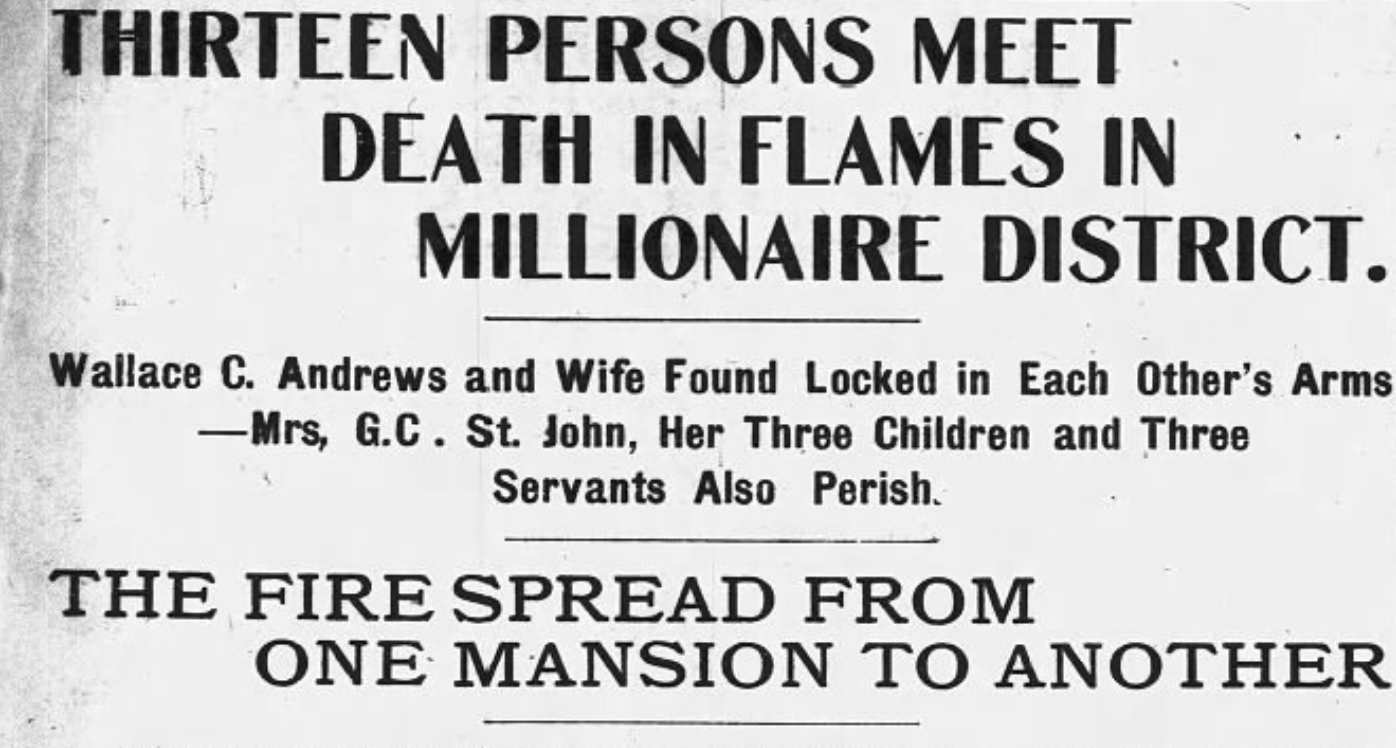

Residents of the building included Edward Markthuber who sat on the jury of an 1899 trial to determine the origin of a headline-making explosion at the home of Wallace C. Andrews, millionaire president of the New York Steam Heating Company[1], in which he and twelve other people perished on April 7th of the same year. After deliberation, Markthuber and his eleven peers determined that the fire was accidental and not caused by a disgruntled servant, as the prosecution suggested.[2] Another tenant was May Atzbach who made waves when she was reportedly cured of her deafness onstage by Darius Wilson, M.D., a physician who proclaimed himself to be the greatest aurist of his (or any) time.[3] Dr. Wilson was praised at the time for offering health insurance to immigrants, despite his dubious claim that he had found the solution to hearing loss.[4] His displays of aural wizardry were popular events and well-attended by eager crowds clamoring to see the medical showman theatrically undo permanent ailments. Wilson was arrested a little over a decade later for selling fraudulent masonic degrees, but surely this incident was not his first deceitful transgression.[5]

The flats were also witness to a rather mortifying misunderstanding for a Mrs, Harriet Mortimer in January 1907. Arrested and discharged the next day, Mortimer—who claimed she was the wife of a Secret Service operative[6]—was accused of evading payment for a COD dress order which she claimed was already paid for in full. Four years later, 22 year-old tenant George Duke was shot and killed by Silas Seabrook during what the Times Union called a “street riot”. His death at the hands of a Black man (a fact prominently mentioned by the paper) was featured in the newspaper as an example of a “real crime wave” in the city—the racial implications are clear.[7]

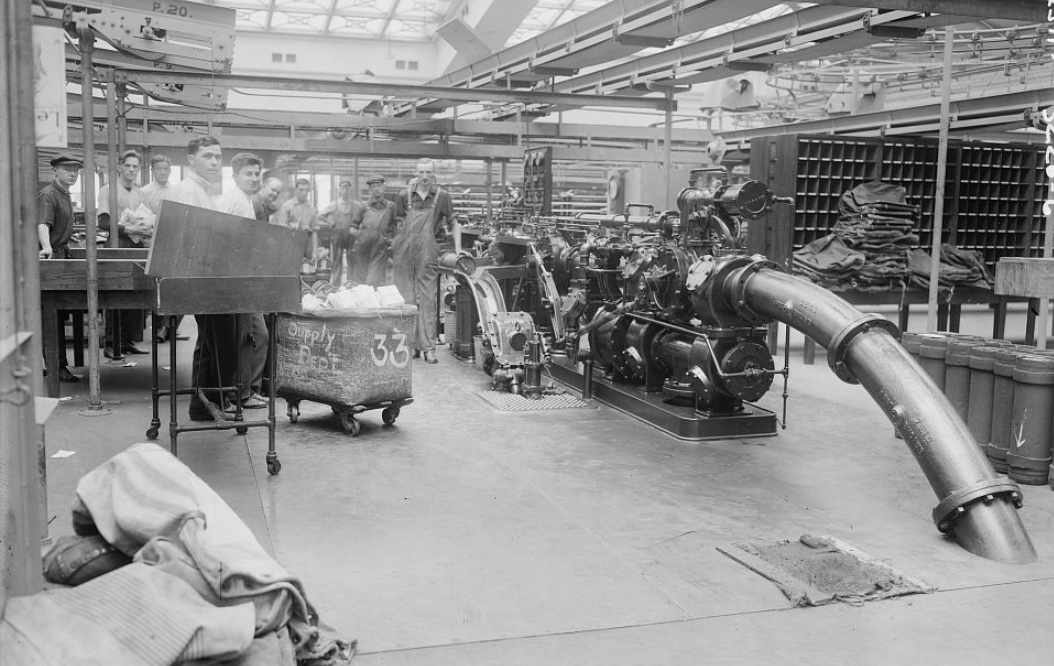

498 Columbus Avenue, one of the building’s alternate addresses, was announced in 1902 as having received a contract to become Station W, one of many terminuses for New York City’s pneumatic mail tube system which was first established in 1897.[8] Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, and Philadelphia were among other cities to receive similar contracts at the time.[9] Station W was to join, as Untapped New York notes, a 27-mile system that connected nearly as many post offices, launching mail from Manhattan’s southern tip to its northern within minutes.

Drew Arch Rest, a shoe shop that advertised “fashionable footwear that keeps the foot small and young and graceful always!” peddled their wares at 504 Columbus Avenue in the early part of the century.[10] A Chinese laundry set up shop in the building’s storefront around the same time, as well. Soon after, the Schuyler Theater (and adjoining Schuyler Food Shop) took up residence on the building’s ground floor, opening on April 2nd, 1937. To accommodate this change, the fourth and fifth stories of the northern half of the building were removed, its remaining windows boarded and barred, and a new roof, sidewalls, and rear wall erected—these alterations were undertaken by well-regarded theater architect, William I. Hohauser. Motion Picture Daily announced the opening of the theater owned by the enterprising mouthful of Zimmetbaum, Knoble, and Yoost, while managing to misspell the theater’s name as “Schuler”.[11]

To accommodate this change, the fourth and fifth stories of the northern half of the building were removed, its remaining windows boarded and barred, and a new roof, sidewalls, and rear wall erected

The theater offered your standard Hollywood fare; a 1939 photo indicates that the day’s bill included The Christmas Carol starring famous character actor Reginald Owen, gangster shoot-em-up Behind Prison Gates, and morality drama They All Come Out. However, The Schuyler offered more than just onscreen thrills. Just months after opening, the venue was one of a handful theaters that experienced a projectionist-led sit-in demanding better working conditions for union members. The operator there locked himself in the projection booth, stocked with enough supplies to get him through the anticipated week ahead.[12] As it happens, his stash went mostly unconsumed—a deal was reached after only twelve hours, resulting in a 50% wage increase and a guaranteed 30-hour workweek.[13]

By the end of the 1960s, the ground floor was occupied by another neighborhood gathering place: Sloan’s Supermarket. Years later, Sloan’s, experiencing decreasing profits, would eventually become Gristede’s Sloan’s before eventually dropping their original namesake (along with the apostrophe) and solely assuming the Gristedes title.

[1] The Buffalo Enquirer, April 7th, 1899. Pg. 1.

[2] The New York Times, May 2, 1899. Pg. 5.

[3] The World, December 9, 1899. Pg. 8.

[4] Moore, William D. Darius Wilson, Confidence Schemes, and American Fraternalism 1869-1926.

[5] The Buffalo Enquirer, August 13th, 1910. Pg. 10.

[6] The New York Times, January 6th, 1907.

[7] Times Union, July 24, 1911. Pg. 2.

[8] https://untappedcities.com/2013/03/15/nycs-pneumatic-tube-mail-network/

[9] New York Tribune, September 28, 1902. Pg. 7.

[10] NY Daily News, March 31, 1930. Pg. 56.

[11] Motion Picture Daily, April 1, 1937. Pg. 10.

[12] Daily News, July 31, 1937. Pg. 198.

[13] Ithaca Journal, July 31, 1937. Pg. 1.

Max Chavez is an architectural historian based in Los Angeles, California.

LEARN MORE ABOUT

504 Columbus Avenue

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 504 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Alfred Gumbs and Luis Torres!