Keeping the Past for the Future

Urban PreservationistsUsing the Upper West Side as our case study, this program explores the development of NYC and the UWS through World War II, specifically considering push-pull factors like gentrification, urban renewal, and more. What evidence of this do we find today?

Using our neighborhood, let’s explore the ideas behind historic preservation and the impacts it has on our neighborhood and communities today, including how we, as citizens, can shape our environment.

- 1624 -Mannahatta Becomes Manhattan

- Mid 1800s - From Farm to Village

- Mid to Late 1800s - Arts and Leisure

- Late 1800s - Residential Development

- Late 1800s - Early 1900s -- Public Transportation

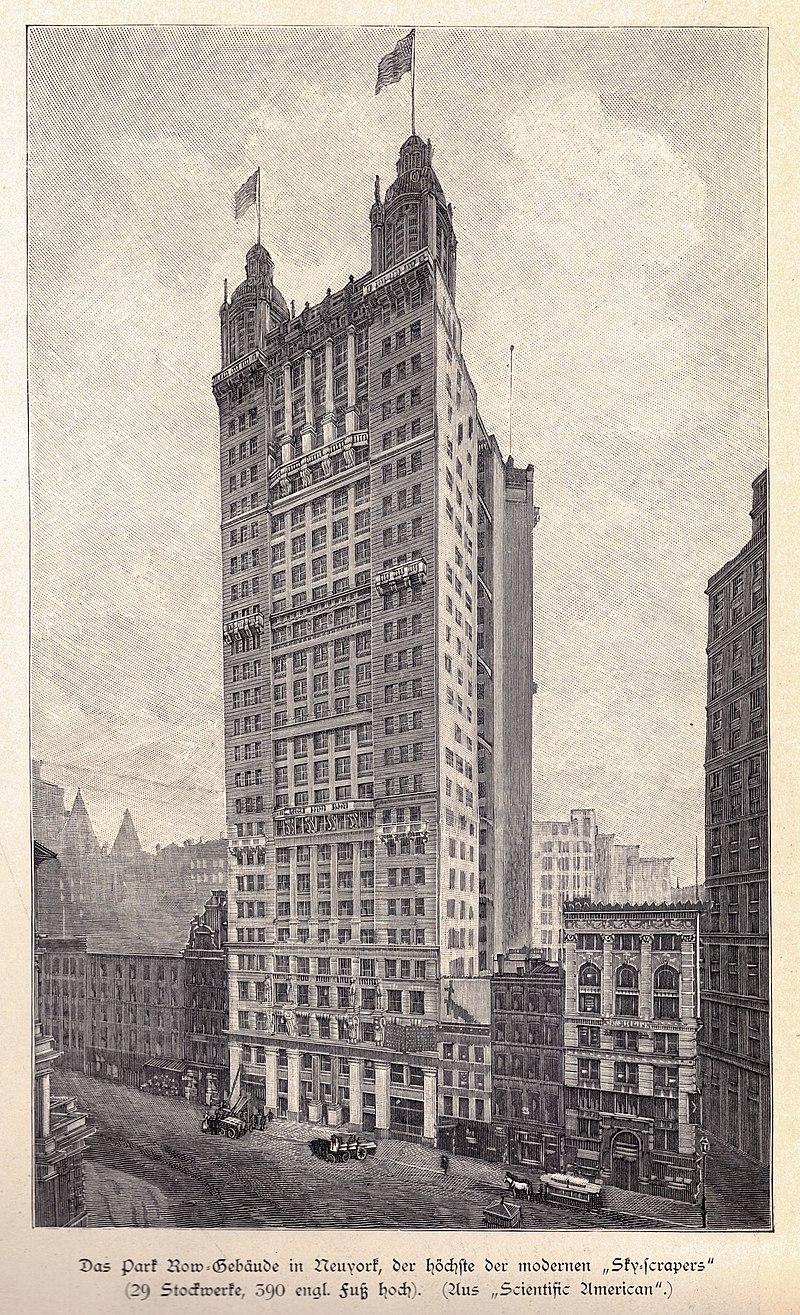

- Early 20th Century - A Recognizable City

-

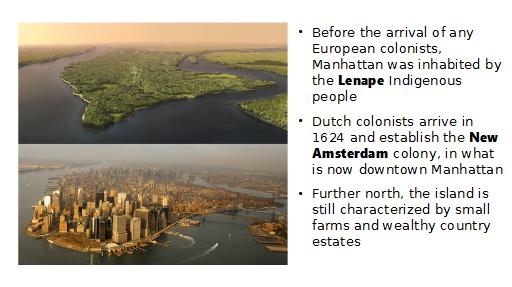

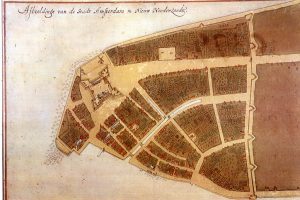

1624 — Mannahatta Becomes Manhattan

Before the arrival of any European colonists, Manhattan was inhabited by the Lenape Indigenous people. Over time, the Lenape were fully displaced from the island by the increasing European colonists. In 1624, Dutch colonists arrived in what is now downtown Manhattan and established the New Amsterdam colony, which existed until it was replaced by British rule. Further north on the island, however, Manhattan was still characterized by rural countryside, small farms and wealthy country estates. The city of New York developed northward from the southernmost tip, but the Upper West Side remained sparsely developed through the Civil War.

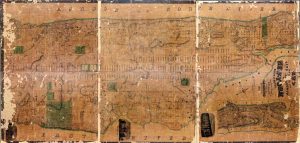

The Castello Plan, a 1660 map of New Amsterdam (the top right corner is roughly north). The fort gave The Battery its name, the large street going from the fort past the wall became Broadway, and the city wall (right) gave Wall Street its name.

-

Mid-1800s — From Farm to Village

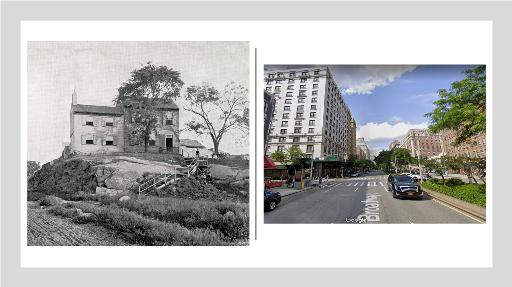

Mid 1800sIn 1703, Bloomingdale Road was built to respond to increasing commerce in the village of Bloomingdale, located in the northern part of the neighborhood now. But for the most part, the natural topography of the Upper West Side proved resistant to development for much of the 18th and 19th centuries. It was very rocky and hilly, which made for smaller farms in its early days. Many steep hills were made of schist, a rock that is very hard and difficult to cut through. After the Croton Aqueduct was built in the 19th century, the arrival of sanitary water for drinking and bathing made more development possible.

- 1879 farmhouse on Broadway at 84th Street

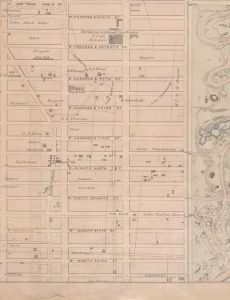

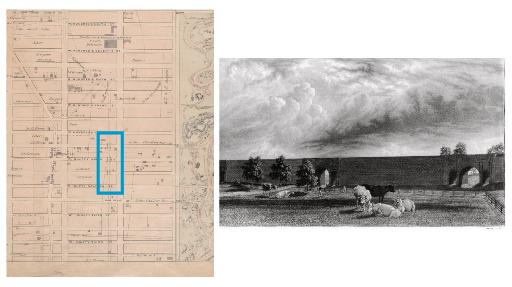

- 1868 map of the UWS. Croton Aqueduct seen between Columbus and Amsterdam where the arches are.

- Aqueduct 19th Century

- 1890 photograph of West End Avenue, looking west toward the Hudson.

-

Mid to Late 1800s — The Arrival of Arts and Leisure

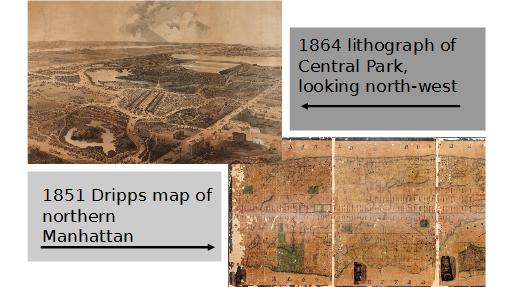

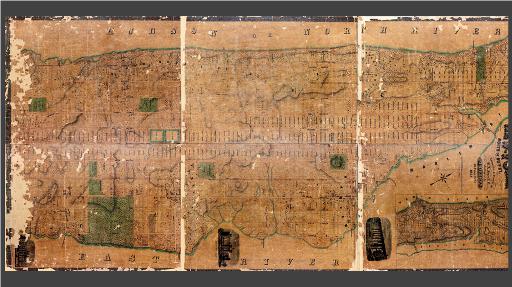

When Central Park was built, the majority of Manhattan’s people still lived downtown; urban planners only guessed that development would eventually spread north to cover uptown. Building the park was a huge effort, with city officials rushing to create a large park on the island before it got too built up to support such an effort. One of the architects, Frederick Law Olmstead, anticipated that the streets alongside the park would eventually be really desirable for residential developers. When the park was built, planners cleared out built communities to use the space, including a prominent African-American community called Seneca Village.

The prospect of having a large park for recreation attracted new residents to the area. Additionally, the American Museum of Natural History began construction in 1869, finishing and opening to the public 8 years later. The museum continued to expand and become more popular over the years.

- 1851 Dripps map of Manhattan, from before Central Park was built

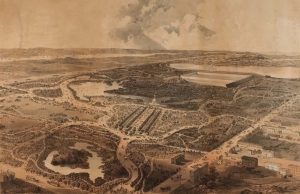

- 1864 lithography of Central Park, looking north

- circa 1890 photograph of the American Museum of Natural History, taken from the roof of the Dakota

-

Late 1800s – A Fashionable Suburb

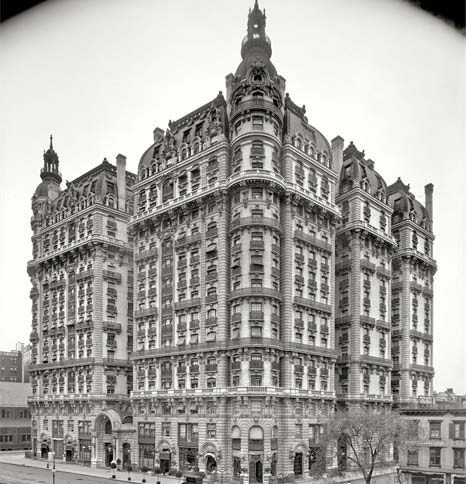

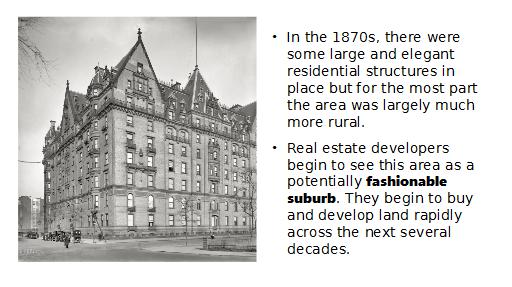

In the 1870s, there were some large and elegant residential structures in place but for the most part the area was largely much more rural. Thanks in part to Central Park and the Museum of Natural History, real estate developers begin to see this area as a potentially fashionable suburb. They begin to buy and develop land rapidly across the next several decades. Brownstones were built on many of the cross streets, and Columbus Avenue was intended to be a shopping district: it featured mostly flat-topped apartment buildings with shops on the ground level. At this point, the neighborhood was referred to as “West End” and was really considered to be separate from New York City. By the end of the century, old Bloomingdale Road, built back in 1703 to connect the city to the northern villages, had a new name: Broadway.

- 1904 photograph of the Ansonia

- 1912 photograph of the Dakota

-

Late 1800s – Early 1900s — Public Transportation

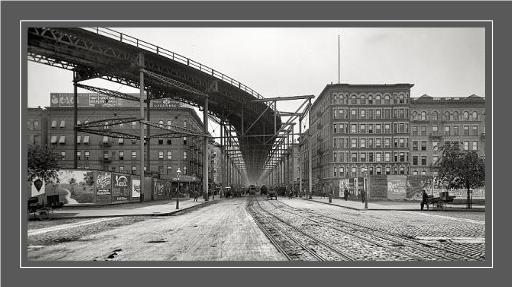

The arrival of public transportation dramatically changed daily life on the Upper West Side. An elevated train ran along Columbus Avenue before the underground system was built. In 1871, it reached 51st Street, and 7 years later stretched up to 91st Street. Not only did the train line physically connect the previous “fashionable suburb” to Downtown, allowing it to become part of the city, but development also sprang up rapidly along the train line. By 1905, an underground train line was built as far north on Broadway as 96th Street. Now, people could live anywhere from the Hudson to Central Park and be able to easily access affordable transportation to their jobs in other parts of the city. When the subway was completed, the properties nearby became more and more valuable.

- Unknown photo date, but it shows the elevated 9th Avenue El line that stretched down Columbus.

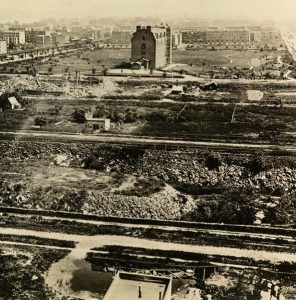

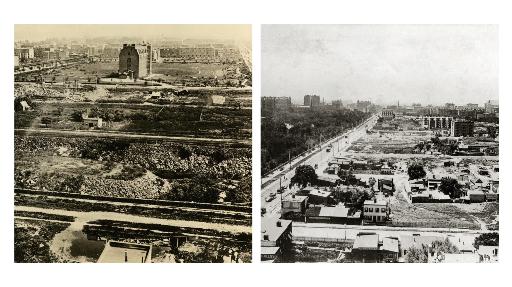

- 1905 photograph of the construction of an underground subway line along Broadway and 96th Street. (the 1)

-

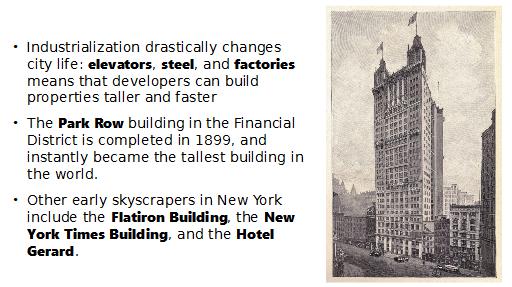

Early 20th Century – A Recognizable City

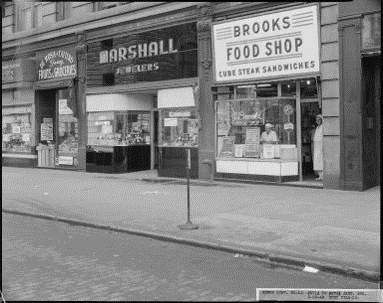

The elevated train line continues expanding and being used through 1940, which encourages storefront businesses to open and thrive, as they are visible and easily accessible to travelers on the street. The first floor of most flat-topped apartment buildings (like the ones visible on Columbus) became stores. As public transportation grew, so did the streets around it; by the 1930s and 40s, the Upper West Side looked recognizably like a part of New York City. Immigrant communities continue to grow in the neighborhood as well. Many families moved out of the increasingly crowded tenements on the Lower East Side in the 20’s and 30’s. In the late 30’s, another influx of Jewish immigrants/refugees arrive from Germany after fleeing the growing threat of the Nazi regime.

- Photograph circa 1940 of the intersection of Columbus Avenue and W. 86th Street.

- Storefronts along Amsterdam Avenue between 72nd and 73rd Streets, from a 1949 photograph.

Session One Slides

How did the Upper West Side, and the whole of New York City, come to be? Let’s trace the history of the city from before European colonization through World War II, and zoom in on how our neighborhood specifically grew to become a part of New York.

Historic photos and maps are excellent primary sources that can put this history into context for us.

Session Two Slides

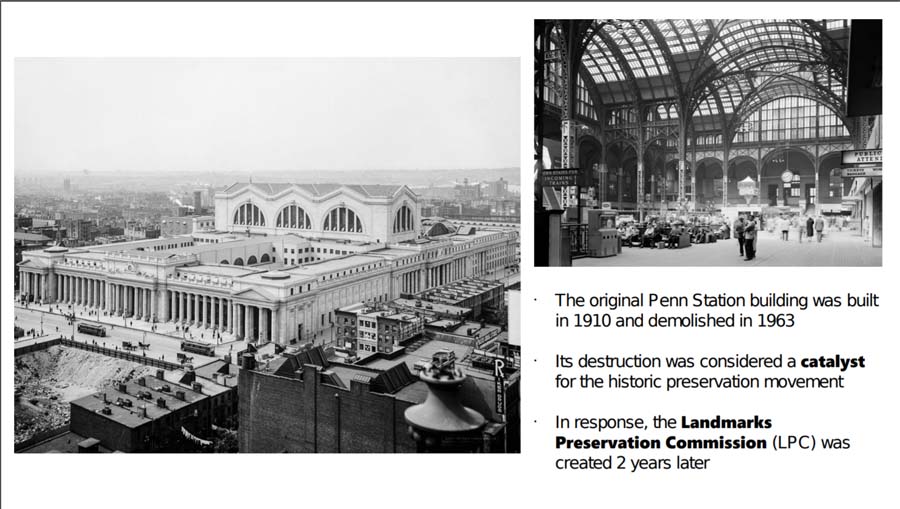

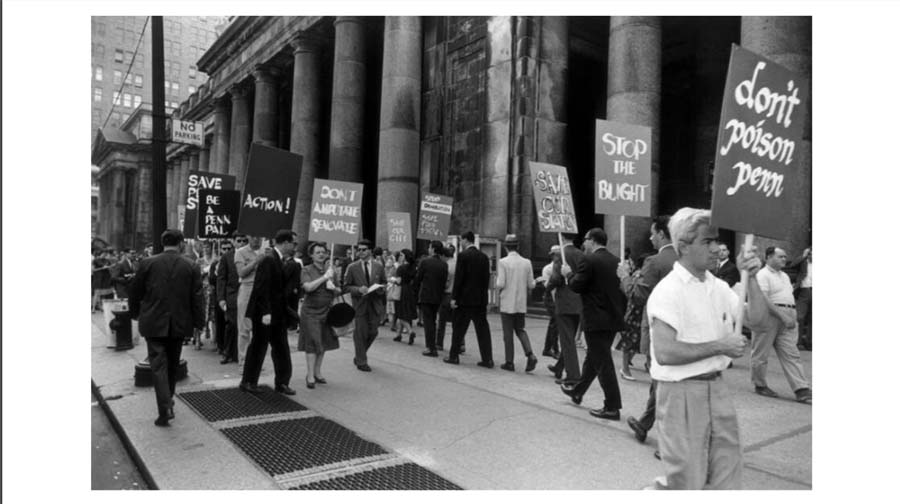

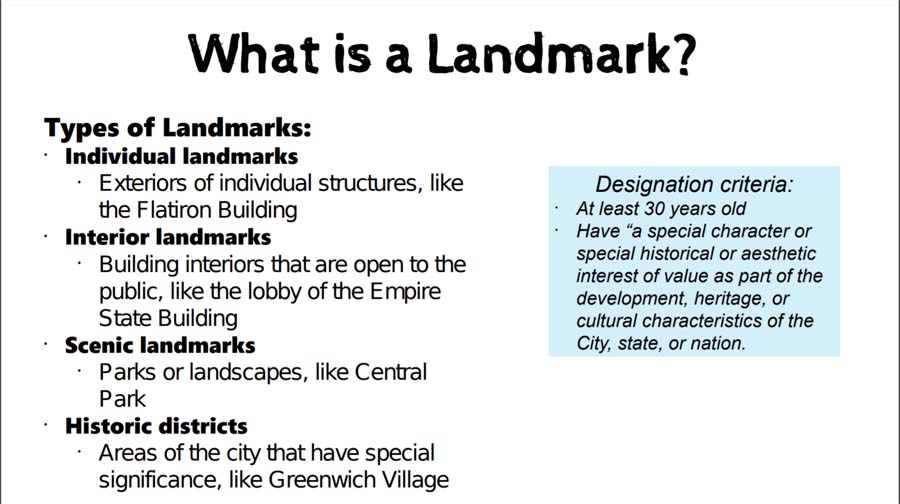

What exactly is historic preservation?

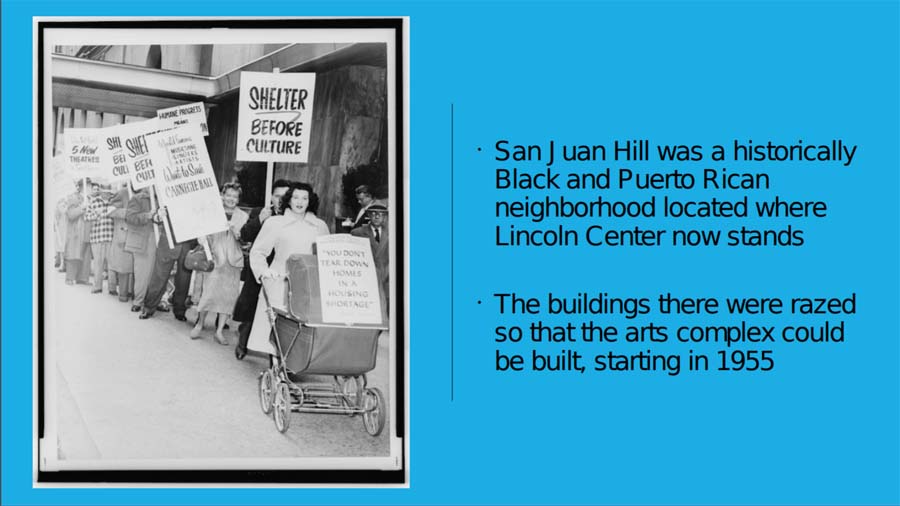

After World War II, development changed in the city. Urban renewal claimed many communities in its push to modernize the city, such as the San Juan Hill neighborhood raized in favor of Lincoln Center.

How do cities preserve and remember their histories? Let’s review the types of landmarks we have today, and think about the impacts they have in modern times.

Resources – Urban Preservationists

Architecture

Basics of Historic Preservation

Economics

Gentrification, Urban Renewal, and Housing

Heritage

Local History

Sustainability

Acknowledgements

KPF is made possible by the contributions of Council Members Helen Rosenthal and Mark Levine, as well as the New York State Council of the Arts (NYSCA) and the Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA). With their support, Landmark West’s KPF program offers a suite of seven 3-part courses aligned with the NYC Core Curriculum in Upper West Side public schools for free every year.