Rutgers Presbyterian Church

234-236 West 73rd Street

by Tom Miller

By the 18th century, the Dutch Rutgers family had established itself in Manhattan with a large estate north of the city and a fine mansion. Henry Rutgers survived service in the Revolutionary War to enter a life of public service and distinguish the family name with his generous philanthropies. One of these would result in the change of the name of Queens College to Rutgers College.

A devout man, in 1798 he donated land to a Presbyterian congregation at what would become the corner of Henry and Rutgers Streets. It was known as the Rutgers Street Church, or more familiarly “The kirk on Rutgers Farm,” and opened its doors for worship on May 13, 1798.

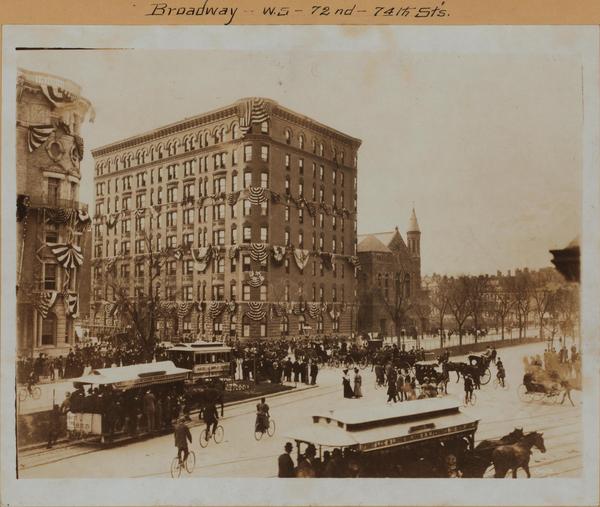

In 1888, after three previous moves, the Rutgers Presbyterian Church congregation acquired a large lot at the southwest corner of Broadway and 73rd Street and hired architect R. H. Robertson to design a forceful Romanesque Revival church on the site. The substantial structure cost $240,500 to construct–more than $6.5 million today.

Thirty years after the building was completed the property on which it sat had become extremely valuable. On the northwest corner was the imposing Ansonia Apartments and Broadway bustled with activity. The New York Times noted in November 1921 “The six lots there were purchased for $93,700. Today the property is worth approximately $1,000,000.”

On December 6, 1919, The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide announced “The Rutgers Presbyterian Church property…has been purchased by Sheriff David H. Knott and Henry J. Veitch, president of the Hotel St. Andrew Co., as a site for a 14-story hotel to cost about $3,000,000.”

The architectural and building firm Fred F. French Company was contracted to design and erect the 500-room hotel, but then things faltered. When the Rutgers Presbyterian congregation celebrated its 125th anniversary in November 1921, it was still in the corner church.

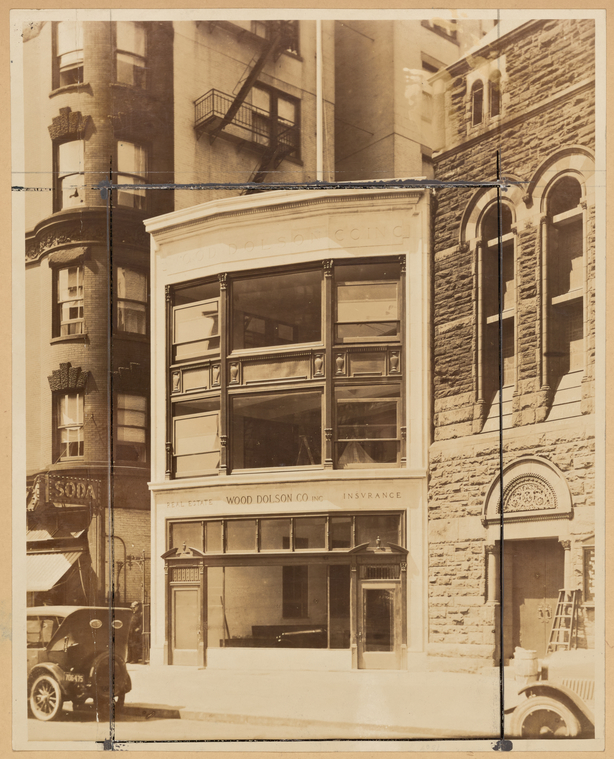

With the hotel project defunct, in July 1922 the trustees leased the vacant plot abutting the church to the real estate firm of Wood, Dolson Co., In. for $12,500 per year as the site of its new headquarters. “The architecture of the new structure will conform with the church building,” announced the Record & Guide.

As 1923 drew to a close the trustees of Rutgers Presbyterian Church thought they had found a solution to getting the most value from their property–a skyscraper church. The concept was becoming popular in large cities. Church buildings were being demolished to be replaced with apartment or office buildings which retained space for the religious organization.

On December 13, 1923, The Hudson Valley Times wrote “Rutgers Presbyterian Church on Broadway at 73rd Street is to be remodeled. The lower floors will be occupied by a branch bank. The church will have the upper part and will gain an income of $25,000 a year to help bear the cost of its program.”

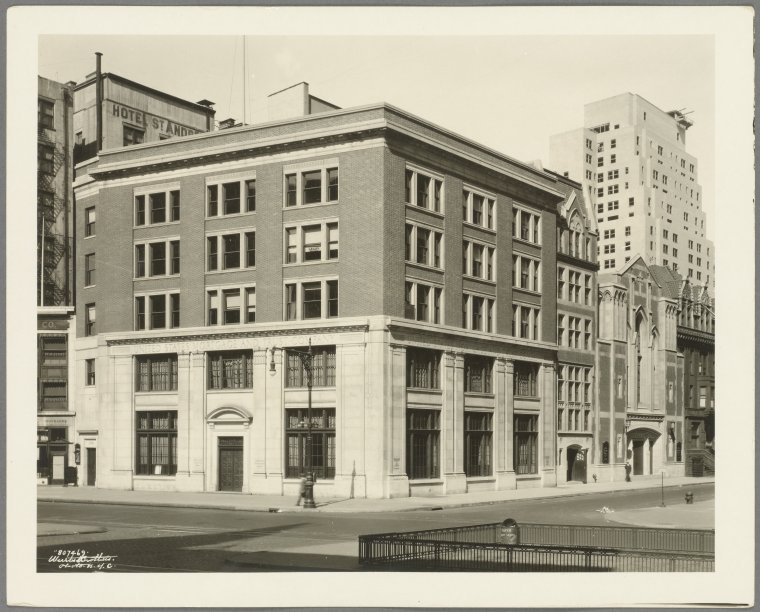

But that plan, too, never came to fruition. Instead, the church leased the corner plot jointly to Wood, Dodson & Co. and the United States Mortgage and Trust Company, while retaining for itself a rear portion of the property for a new, smaller building. The cornerstone was laid on February 14, 1925 “in the presence of several hundred parishioners and a number of distinguished clergymen,” according to The Hancock Herald.

As 1923 drew to a close the trustees of Rutgers Presbyterian Church thought they had found a solution to getting the most value from their property–a skyscraper church. The concept was becoming popular in large cities. Church buildings were being demolished to be replaced with apartment or office buildings which retained space for the religious organization.

Within the cornerstone were placed documents relating to church calendars, ministers, photographs of the exterior and interior of the old church, a copy of the leases for the corner site, and related papers. The article noted, “The cornerstone weighed two and one-half tons.”

The trustees had hired Henry Otis Chapman to design its new home. Construction was completed early in 1926 and the dedication ceremonies took place on March 21. Chapman’s red brick and limestone sanctuary and church house were a 1920’s take on English Gothic and, in the case of the church house, neo-Tudor.

The entrance doors were slightly recessed within an elliptical arch; its width was carried onto the three pointed-arched stained glass windows directly above. Limestone was used on either side of the gable to create grouped, blind Gothic arches that simulated towers.

Inside Gothic co-existed with the waning Arts & Crafts movement. The oak elements–pews, pulpit, railings, and such–were carved with Gothic arches and trefoils and sat upon a pavement of Arts & Crafts mottled tiles. Worshipers accustomed to R. H. Robertson’s highly decorated sanctuary now found plain plastered walls free of frescoes or nearly any other ornamentation.

Three years later the country was overwhelmed by the onslaught of the Great Depression. Political and social issues often made their way to the pulpits of Manhattan churches and in 1934 the Rev. Daniel Russell gave his opinion of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration to the congregation of Rutgers Presbyterian.

On July 19 the Stamford Mirror-Recorder reported that he “told his congregation that the N.R.A., far from bringing the masses any relief, had in fact reduced even further their living standards. He said that he would render no greater service from the pulpit than to point out to the wage earner that a planned economy offers but little hope, in the long run, but rather blasts his chances for independence, prosperity, and the good life.”

With tensions building in Europe, the issue of war and education was addressed in the church in January 1936. A conference of “peace educators” concluded “The trouble about peace education along idealistic lines is that it rests so largely on emotional appeal, a psychological factor which can never be trusted in the excitement and alarm of an impending war,” as reported by the Buffalo Courier-Express on January 19. “The war-makers are past masters in the treatment of mass psychology when popular ideals are all too easily confused.”

A situation that would bring nationwide press began the following year when the church held a contest among artists for a 26-foot-wide, 35-foot-high mural for the unadorned rear chancel wall. The design of well-known muralist Alfred D. Crimi won the $6,800 commission for his Spreading the Gospel.

Crimi worked on the mural for two years. Upon its unveiling on November 20, 1938, the pastor, Dr. Daniel Russell, described it as a picture of “the human Christ, whose muscles have hardened with the toil of rude and heavy tools in a primitive carpenter shop.” A large number of the female members disagreed, finding it disturbing to look at the muscular naked torso of Christ throughout the service.

Late in the summer of 1946 Crimi was in Manhattan and dropped into Rutgers Presbyterian Church to visit his work. The Rome [New York] Sentinel reported that “he was horrified to find that it had been blotted out by the church authorities.” The mural had been erased by a thick coating of white paint.

“It was explained by the Rev. Dr. Ralph W. Key, the pastor, that members of the congregation felt the central figure of Christ ‘portrayed physical rather than spiritual strength–they just didn’t like it and when the church was redecorated the mural was included in the plans.”

Incensed and indignant, Crimi went to court for damages. He admitted to reporters that while “he could not legally force the church to restore the mural, he would attempt to force the issue on moral grounds.

Crimi’s case was interesting. He said the church had replaced his mural with “an undignified burial shroud” and asked the courts to “protect his honor and reputation.” (And grant him $50,000 as well.) To do so attorneys and a judge would have to decide if such a thing as “moral ownership” existed.

It didn’t.

After dragging on for years, the courts ruled on January 29, 1949, that “when the picture has been painted and delivered to the patron and paid for by him, the artist has no right whatever left in it.”

In the meantime, an annual occurrence at Rutgers Presbyterian Church, going back to around 1929, was the two-day Interdenominational Missions Training Institute. Each year’s gathering had a theme. With World War II raging in 1941, the sessions focused on “Democracy at Home and the Old Order Round the Globe.”

Independent schools and small colleges routinely used the auditoriums of churches for their graduation ceremonies. By the 1960s Rutgers Presbyterian was the annual venue for the commencement exercises of the American Academy-McAllister Institute of Funeral Service in New York–perhaps less expected than the more common beauty institutes and industrial schools that filled New York churches at graduation time.

Crimi was in Manhattan and dropped into Rutgers Presbyterian Church to visit his work. The Rome [New York] Sentinel reported that “he was horrified to find that it had been blotted out by the church authorities.” The mural had been erased by a thick coating of white paint.

In 2013 Rand Engineering & Architecture, DPC, initiated a restoration of the church. The all-inclusive project replaced the roof, repaired the masonry, and in 2019 the stained glass windows, including the rose window, designed by G. Owen Bonawit, were restored. While in overall good shape, the glass was dirty and some panes were cracked.

While work is still necessary on the other windows, the restoration efforts over the years brought the facade of the Rutgers Presbyterian Church back to its 1926 appearance.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com