St. James Court

by Tom Miller

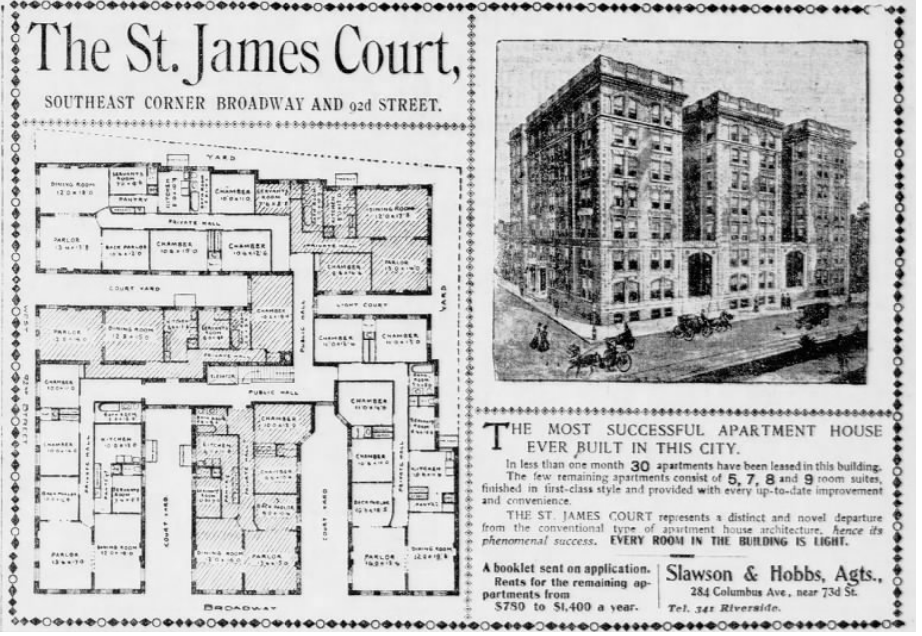

Real estate developer Jacob Axelrod was a busy man on the Upper West Side at the turn of the last century. On February 3, 1900, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that he had just purchased the southeast corner of Broadway and 92nd Street where he “will erect a 7-story apartment house.” The article noted, “he has just finished two six-story apartment houses in 93d st, near Riverside Drive.”

Axelrod hired architect George Fred Pelham to design his newest project, which would be called the St. James Court. Completed on October 1, 1900, his brick and stone structure was designed in the Renaissance Revival style, the upper façade peppered with limestone balconies and scrolled keystones. To provide the interior apartments with ventilation and natural light, Pelham inserted deep light courts into the structure—giving it the outward appearance of four buildings. He unified the segments by straddling the gaps of the light court at the second floor with balustrade-topped arches, which melded seamlessly with the window balustrades of the third floor.

More than a month before the building’s completion, it was half-rented. Brokers said it was Pelham’s “unique construction,” the use of light courts, that prompted “such phenomenal success.” On August 28, 1900, the New-York Tribune said, “The apartments range in size from five to eight rooms, and the rents are moderate. The most modern appliances for the convenience of tenants have been installed in this apartment house.” Rents ranged from $750 to $1,400 per year—about $3,700 per month for the most expensive by today’s standards.

The residents of the St. James Court were, expectedly, well-to-do. That did not prevent them from suffering troubles and, often, tragedy. On Saturday afternoon, June 22, 1907, for instance, Mrs. Eliza Leavitt was sitting in the waiting room of the Hoboken Ferry terminal at the foot of West 23rd Street, when “she was stricken with an epileptic fit and in falling on the floor suffered a broken collar bone and several lacerations about the head,” as reported by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The newspaper said, “Her fall caused considerable excitement in the waiting room, which was crowded.” She was carried into an office and a doctor from New York Hospital was summoned. He revived her and she was taken to the hospital.

Mrs. Eliza Leavitt was sitting in the waiting room of the Hoboken Ferry terminal at the foot of West 23rd Street, when “she was stricken with an epileptic fit and in falling on the floor suffered a broken collar bone and several lacerations about the head,” as reported by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Much more tragic was the accident that had taken place a few days earlier. St. James Court resident Clarence McKenzie was president of the Standard Brake Company and an avid automobilist. On June 6, he prepared to leave the apartment to take part in the Albany Auto Run, a 200-mile endurance run from New York to Albany sponsored by the New York Motor Club. But his wife, haunted by a persistent premonition that he would meet harm, begged him not to go. The New-York Tribune said he answered, “I’d like to, myself; but I can’t draw back now.” Instead, he promised not to go further than Poughkeepsie.

He sent a message from Poughkeepsie to his wife late that morning, saying that she would hear from him later. But his promise to stay in Poughkeepsie was only a guise to calm his wife. The following morning the New-York Tribune began an article saying “With a shock which hurled motor car and passengers skyward like rockets, a high speed electric trolly car crashed into one of the automobiles” in the race. Clarence McKenzie was killed instantly, just a mile south of Albany.

When she had not heard from her husband by 9:00, Mrs. McKenzie phoned the Ten Eyck Hotel in Albany. The switchboard operator contacted a member of McKenzie’s party in his room. Sadly, “The wires crossed, and [Mrs. McKenzie] heard Mr. Richardson…say to someone: ‘Don’t tell her. He’s all cut up.’” The New-York Tribune said, “Then she swooned, and physicians had to be called to attend her. Later a telegraph message reached Mrs. McKenzie telling the details of the accident.”

In January 1908 real estate dealer and promoter Clinton O. Burling died from pneumonia. His wife, Frances Van Ness Burling, descended into what friends described as “a continual state of melancholia.” The New York Times added that she “brooded so that it is thought her mind became unsettled.” And, indeed, two weeks after Clinton Burling’s death, on February 5, Frances’s maid, found her dead from inhaling illuminating gas.

Equally tragic, but more bizarre, was the case of Henry Appelius and his wife, the former Harriet Simpson. Henry, who had been the general agent of the New York Life Insurance Company prior to his retirement in 1899, was suffering from locomotor ataxia, a progressive neurological problem that affects motor skills. On the afternoon of January 10, 1909, he told Harriet he was not feeling well and went into a bedroom to lie down. A few moments later she heard the report of a revolver and rushed in to find her husband dead.

New Yorkers were surprised when the terms of his will were published in May that year. He gave “Isabelle Smith, a negro servant,” $1,500, and divided the bulk of his estate between his two executors. The Sun reported that he gave Harriett, “only a life insurance of $3,000, declaring that her conduct had been unwifely.”

Bad luck for the St. James Court continued in 1912. Workmen who were cleaning the façade began lowering scaffolding on June 24, just as Catherine Loftus, a maid at 173 West 93rd Street, was passing by. The scaffolding became caught in the fourth-floor coping, and dislodged a stone, which fell and hit Catherine in the head, killing her instantly.

Living in the St. James Court in 1913 was the family of Martin Standroup, an engineer on the Morgan Steamship line. That April 16-year-old Anna Standroup, according to her story, met a man at 119th Street and Central Park West, who “persuaded her to go to a photograph studio in the Bronx.”

When Anna did not return home, a general alarm was sent out to find her. It would take nine months for police to do so. On January 21, 1914, she was discovered in a studio on East 149th Street. At first, Anna was charged with “being an incorrigible and at the request of her father was sent to the Florence Crittenton Home,” said The Evening Telegram. “The girl then broke down and told the detectives her story.” She said that at the photography studio she was forced to pose for indecent photographs. She was then taken to an apartment where she was made “to receive men callers.” Two men and a woman were arrested for conducting “white slavery,” taking and selling indecent photographs. The Evening Telegram said, “The police expect to make a more serious charge to-day.”

…when he rang the Selbys’ doorbell, “he said that Selby came to the door in his night attire and punched the youngster for waking him up,” as reported by The Sun.

Perhaps the most celebrated tenant of the St. James Court was boxer Norman Selby, whose professional name was Charles “Kid” McCoy. Edna Fernanda Valentine was Selby’s sixth wife, although he had been married seven times before (he had married Julia Crosselman three times). On the morning of December 31, 1916, Edna went shopping. As was customary, her packages were wrapped and delivered by the department store’s messenger boy.

At 11:00 that morning John Montgomery brought her bundle to the St. James Court. But when he rang the Selbys’ doorbell, “he said that Selby came to the door in his night attire and punched the youngster for waking him up,” as reported by The Sun. Selby’s defense was “that the boy’s pounding on the door disturbed his eleven-year-old daughter, who was suffering from pneumonia. Selby said he cuffed the messenger to make him cease his disturbance.” The boxer was held on $500 awaiting trial.

Another well-known family to live here was the Townes. Edward Owings Towne was a playwright with an international reputation. His son, Fenimore Cooper Towne, was an actor and playwright. In January 1918 The Dramatic Mirror noted that Fenimore “had recently devoted himself to motion pictures as personal business manager for leading directors.” In November 1917 Fenimore fell ill and died in the St. James Court apartment at the age of 26 in January 1918.

Others involved in the entertainment industry over the years included stage actress Marie Train Moller, and actor William Friend. Although the storefronts along Broadway, today, are a hodgepodge of signs, little else of the St. James Court—including its marvelous entrance portico on West 92nd Street—has changed.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 214 West 92nd Street:

Meet Delano Guerselli!

Meet Nirit Reani!