A Landmark for Women’s Suffrage

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In 1887 real estate developers Benjamin A. and George N. Williams hired the firm of Thom & Wilson to design two mirror image apartment houses at 1426 and 1428 Ninth Avenue (changed to 505 and 507 Columbus Avenue in 1896). The architects were directed to include two storefronts at ground level.

The buildings, completed in 1888, sat mid-block between 84th and 85th Street. That they were faced in brownstone is not surprising, given that the Williams also ran one of the oldest stone contracting businesses in the United States.

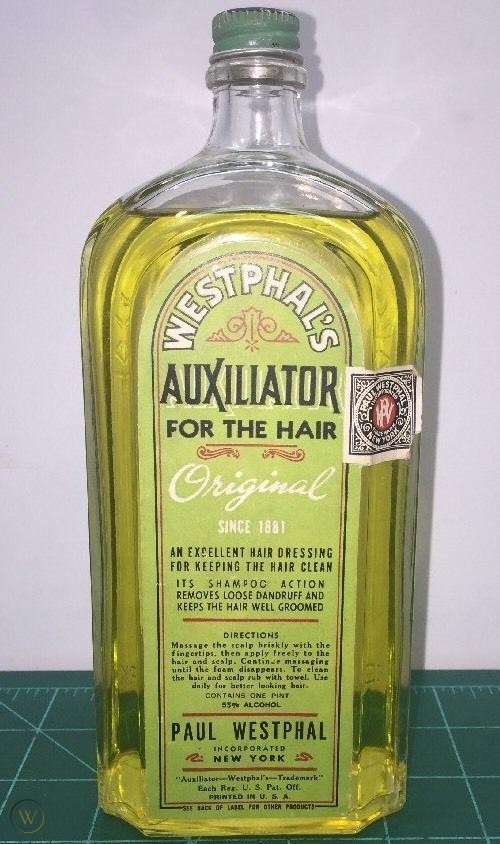

The southern storefront became home to P. Westphal’s barbershop. The German-born barber would remain in the space into the early 20th century. In 1890 he paid $55 per month for the space, and an addition $12 for use of the basement (a total rent of about $1,940 today). It was not until 1900 that his rent was increased by $5 per month.

There were two apartments per floor in each building. Tenants paid varying rents depending on the apartment, but in 1890 they averaged about $21, or just over $600 a month in today’s money. There was a problem keeping the buildings full and in 1895 there were nine vacant apartments.

M. D. Corste, for instance, could afford to own his own horse and delivery wagon; but he was not affluent enough to hire a driver. While working on November 22, 1891 he suffered a terrifying accident. The New York Times reported that he “was knocked down and trampled upon at Eighty-fifth Street, corner of Columbus Avenue, last evening by a horse that he was driving and which he had left standing.”

The tenants were middle to upper-middle class. M. D. Corste, for instance, could afford to own his own horse and delivery wagon; but he was not affluent enough to hire a driver. While working on November 22, 1891 he suffered a terrifying accident. The New York Times reported that he, “was knocked down and trampled upon at Eighty-fifth Street, corner of Columbus Avenue, last evening by a horse that he was driving and which he had left standing.” A doctor diagnosed him with a fractured collar bone and lacerated scalp. The feisty Corste did not allow his injuries to slow him down. “He was, however, able to go home,” said the article.

In 1882 Congress passed a race-based immigrant act, the Chinese Exclusion Act. Naturalization, it was declared, was only for whites and blacks, and Asians were neither. The new law limited the number of Chinese allowed to immigrant into the United States.

These negative efforts were not enough for Frank Wayland, who lived at 505 Columbus Avenue in 1897. Wayland owned several steam laundries and was “an intense rival of the Mongolians,” according to The Daily Leader on September 2 of that year. Wayland saw the Chinese as a direct threat to his businesses. He launched a blatantly racist campaign from his apartment, issuing circulars that warned that Chinese laundries throughout the city were harboring lepers. Rather amazingly, his scare tactic worked and even caught the attention of President Woodrow Wilson, who ordered that “All the Chinese laundries in this city are to be ransacked, turned inside out and topsy turvy by the health authorities in a search for hidden lepers,” said The Daily Leader. The President’s order was a direct result of Wayland’s circulars.

Frank Wayland was “much gratified” by the Government’s response. He guaranteed that “when the several thousand Chinese laundries were searched enough genuine lepers would be dragged out to swell the exiled population of North Brother Island by at least a score.”

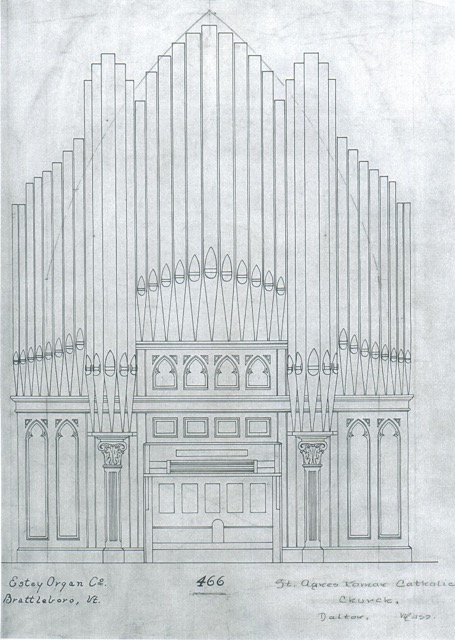

While P. Westphal continued cutting hair in 505 Columbus Avenue, the shop at 507 saw several tenants. It was the uptown showroom of Estey Organs at the turn of the century, followed by Benjamin Schneps’s grocery store in 1905, and a furniture and upholstery store by the outbreak of World War I.

Each year on Election Day the city leased 507 Columbus Avenue as a polling place. In 1917 Republican Mayoral candidate William Bennett cast his vote for himself here. But the humble location drew much more attention six months later when women registered to vote for the first time.

On May 26, 1918 The Sun reported, “Miss Mary Garrett Hay, chairman of the Woman Suffrage party…was the first votress to enroll in her district. The place was a furniture store at 507 Columbus avenue and the time four minutes at 8 A. M.” Joining Mary Hay was Carrie Chapman Catt whom The New York Herald said “has waited thirty years for the privilege of casting her ballot.”

During World War II Fred Gilbert lived here. He made a living as an elevator operator, but on January 18, 1945 he attempted to augment his income by purse-snatching. He picked the wrong woman.

Ella Bonifay’s husband was fighting overseas and, a true Rosie The Riveter, “to help out on the home front she has been working as a welder at the Hoboken, N. J. yards of the Todd Shipbuilding Corporation,” explained The New York Sun. Her job earned her the nickname among friends and coworkers as Ella the Welder. It also taught her self-reliance and grit.

During World War II Fred Gilbert lived here. He made a living as an elevator operator, but on January 18, 1945 he attempted to augment his income by purse-snatching. He picked the wrong woman.

That January night she was walking home from church along West 80th Street when Fred Gilbert suddenly grabbed her from behind. The Sun said that she “handles her own assailants when an emergency arises…Mrs. Bonifay didn’t scream but took matters and her assailant into her own hands.” Gilbert escaped from Ella’s onslaught but was captured a block away by two policemen: “there he put up a terrific struggle and it took their combined efforts with nightsticks to subdue him and get him in shape for the police.”

The space that had been P. Westphal’s barbershop for decades became Silverbird restaurant in May 1986. Opened by Reuben Silverbird and his wife, Inge, it was the first Native American restaurant in the Tri-State area. Silverbird told a reporter, “Too many people know too little about Native Americans beyond stereotypes presented in films and on television.” The fare included dishes like buffalo, rabbit and rattlesnake.

The 1990’s saw two bars in the stores. Venue opened at 505 in 1998 and Honeysuckle was already in 507. In 1992 it advertised “jam session for musicians or singers with the house band on Mondays.”

The turn of the century saw restaurants replace the bars. Jean-Luc, a “classy expensive bistro,” according to one critic, opened in 507 and Mod restaurant in 505. More recently Kefi, a Greek restaurant, and vegan eatery Blossom, found homes in 505 and 507 respectively.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

505-507 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 505-507 Columbus Avenue: